“The Brutalist” Production Designer Judy Becker on Designing Fictional Mid-Century Modernist Masterpieces

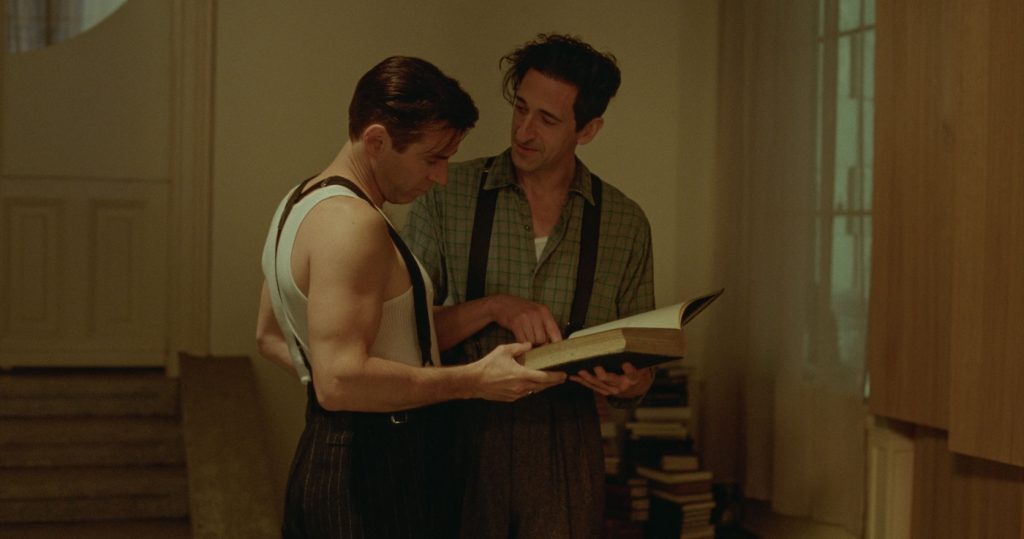

A World War II refugee architect and a robber baron meet in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and modernist design history is made. The premise of The Brutalist, a 3.5-hour critical darling and Golden Globe winner from writer/director Brady Corbet, is as American as apple pie. But from the moment Holocaust survivor Làszló (Adrien Brody) pulls into New York Harbor, the film was shot in Europe. Working primarily in and around Budapest, production designer Judy Becker (Carol, Brokeback Mountain) beautifully transformed the city into mid-century American urbanity.

Becker’s worked on plenty of “wrong place, wrong time” projects in her career. “I don’t think it was more challenging than other period movies I’ve done,” Becker said. Whereas US cities have rapidly gentrified, she was able to use a large industrial area in Budapest for scenes in New York and Philadelphia. For his assimilated cousin Attila’s (Alessandro Nivola) furniture store, where Làszló first lives and works stateside, the production designer scouted a single Budapest building that had never before been filmed.

To lay out the shop, Becker’s set decorator, Patricia Cuccia, drove across Canada sourcing mid-century furniture off Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace, shipping it off to Hungary along with vintage American wallpaper from an independent US source Becker prefers to keep a trade secret, but has relied on for 20 years. “She somehow manages to restock, and I don’t know how she does it,” she said. These staid elements became the stylistic foil to both Làszló’s celebrated past and his present ambitions. He takes over Attila’s shop’s windows with a modern, Brutalist desk made of pipe and webbing, which Becker designed herself. She was inspired by Bauhaus tubular steel forms as well as the American furniture surrounding Làszló. “We took drawers from one of the pieces of furniture in the store, sanded off some of the detail, but kept the hardware on,” Becker said, embracing the idea that Làszló, at that point in time, would have been inclined to reuse materials as well as influenced by his environment. “I also felt that after his experiences, he was a little depleted creatively, so he had his roots in the Bauhaus, but then was starting again with what was around him.”

Làszló’s breakthrough opportunity arrives at the store in the form of Harry (Joe Alwyn), the son of local magnate Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce). Harry commissions Làszló and Attila to renovate his father’s library, which Làszló transforms from a dark, haphazard space into a light-filled room distinguished by built-in rows of modernist shelving closed with a nifty, minimal, swinging door mechanism. In the script, the renovation was described as modern, with a flower opening, which Becker could picture, “but it was hard to see how it would practically work in a space. And Brady wasn’t attached to that particular implementation,” she said. Becker had the idea on the spot to change the shape of the room with a forced perspective via angled wall cabinets.

Even though it first meets with Harrison’s rage, the library is a masterpiece. A steely WASP used to getting his way, Harrison plucks Làszló from his blue-collar job to embark on a grand joint endeavor—a legacy-cementing institution on a hill, combining church, community center, sports hall, and screening room. Becker began working on the Institute before she even officially signed onto the film. Corbet and the producers “knew we weren’t going to build the whole thing, but they wanted to express that some of the Institute was being built. And in order to do that, they needed a design,” she said.

One of the hardest aspects of designing the Institute was incorporating Làszló’s influences, which included his experience in concentration camps. Recalling a synagogue in her hometown, Becker first envisaged subtly incorporating the Star of David into the design, for which she was otherwise inspired by crematoriums, factories, and the work of Japanese architect Tadao Ando. It was difficult to make it work. “Instead, I went full-on with the cross. And that was partly aided by looking at the concentration camp layouts because they were all laid out in a T-intersection, with the barracks on one side,” Becker said. Having also observed that in Central and Eastern Europe, where Làszló hails from, window mullions are often in the shape of a cross, the production designer tied this element to the character’s personal history. “I’ve always found that very interesting, that for Làszló, as a Jew, he was living in that environment, then he’s in a concentration camp, then he is asked to build a church,” she said. For the Institute’s final design, Becker incorporated raised sections that form a cross that’s only visible from above.

With the help of Harrison’s lawyer, Làszló brings his wife, Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), and niece, Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy), to Pennsylvania. Harrison abandons the Institute’s construction after a train carrying materials for it derails, firing everyone. Work eventually resumes, but Harrison, seeing Làszló on a helpless course of self-destruction, violently brutalizes the architect in a marble quarry. Despite this, the project gets done, and in an epilogue, Làszló’s lifelong career is celebrated in Venice, with no Van Burens to be seen. Becker designed the Institute’s entrance to be intentionally claustrophobic, with a narrow hallway separating the rooms on either side. “But gradually, as the hallway went on, it opened up into the church, and after that, there was an exit out that led to freedom,” Becker said, an exit that seems metaphorical not just to Làszló’s escape from Europe, but his survival of Harrison, the film’s other brutalist.

The Brutalist is in theaters now.

For more on The Brutalist, check out these stories:

“The Brutalist” Composer Daniel Blumberg on Blending Genres in Brady Corbet’s American Epic

Featured image: Adrien Brody in The Brutalist. Courtesy A24.