“Maria” Cinematographer Ed Lachman on Painting Angelina Jolie’s Mythic Opera Legend With Light

Passionate Greek-American soprano Maria Callas was the world’s premier opera star when she was struck with various ailments that limited her capacity to sing. She led a life rivaling any opera drama, including a tumultuous relationship with Aristotle Onassis and explosive interactions with collaborators and fans that made her increasingly controversial. She said, “I will always be as difficult as necessary to achieve the best.”

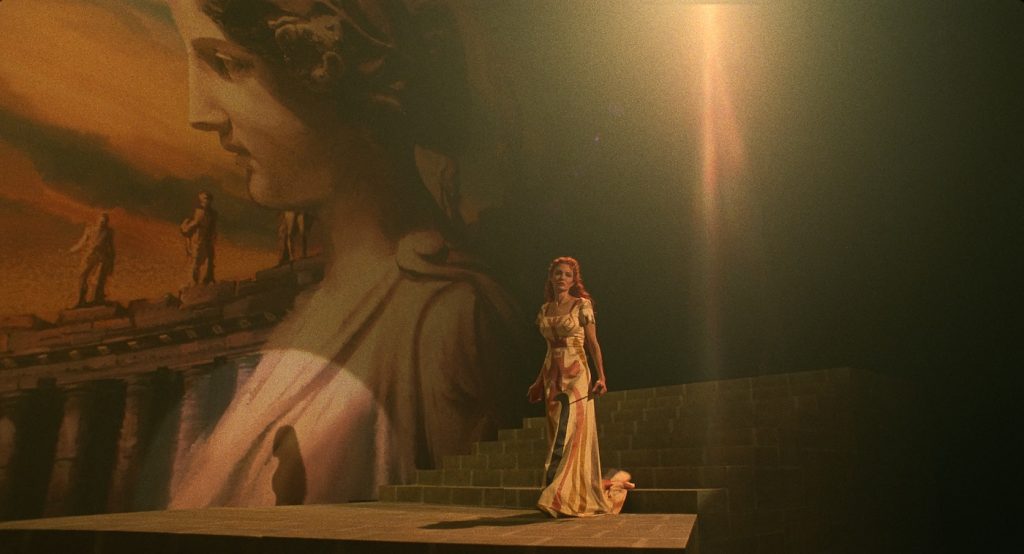

Director Pablo Larraín chose to highlight Callas in his new film Maria. Lauded for Spencer and Jackie, which brought stories about Diana Princess of Wales and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis to the screen, Maria continues his examination of complicated women in the public eye. Starring Angelina Jolie as the exacting and enigmatic performer, the film considers her last weeks of life before death from a heart attack in 53. Callas was living in relative seclusion in Paris, liberally self-medicating with dangerous drugs and undertaking risky behavior. Through Steven Knight’s screenplay, Larraín leverages a mixture of flashbacks, present-day experiences, and a fair number of drug-fueled hallucinations in imagining Callas’s last days.

There’s a good reason Maria cinematographer Ed Lachman was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Middleburg Film Festival in October of this year. The three-time Oscar nominee has lensed some of the most beautiful films of recent history, including Todd Haynes’s Far From Heaven and Carol and Larraín’s most recent feature, El Conte. Lachman approached Maria as if filming an opera, with what he calls “a moving proscenium.” He also worked to recapture the light and color of Paris while on location in Hungary.

The Credits spoke to Lachman about how he created the visual language of Maria, a film that has put him on the Oscar nomination shortlist for Best Cinematography.

Many of the buildings that gave Paris that famous, luminous light were created by Haussmann, but Maria was filmed in Budapest. Can you talk about finding the right building and recreating that light?

There is one shot where you see Maria’s actual apartment. It was a two-shot of her walking with Mandrax before they went to the Trocadéro. Anyway, even though it was a set we created, we were in a real location, in a building in Budapest that Pablo and Guy Hendrix Dyas, the production designer, had found and felt had the right bones. So many of the beautiful old apartments have been or are being renovated, but that apartment building hadn’t been renovated yet, so they could go in and make all the changes they wanted. The problem is it was on the 6th floor, so I had to get 90 or 120-foot cranes and put them outside each window.

Why was that?

Pablo used what I call a moving proscenium frame, which meant using lenses anywhere between 21 and 28mm; I didn’t have anywhere I could hide the lights. I put China balls over the chandeliers, but if I put a light, the camera would see it, so I decided early on that I would light from the exterior with these big HMI lights. The problem for me was, how do I vary it so we don’t feel like we’re always in the same light?

What did you do?

I did that in two ways. One was through color temperature, by changing the time of day with gels on the lights. The lights are daylight-balanced, but you can use orange filters to make them warmer. The direction of the light and the height of the light to the window outside would change. The real source of the light coming in in the morning would be lower, where you would see the shadow of the window higher, and as the day went on, the shadow of the window would go lower. When we were shooting, I was very sensitive to what time of the day it was in the storyline. I had to place the lights in the right position to show the time of day. The other thing I realized was that in Paris, the streets aren’t very wide apart from each other, except on the boulevards, so the light moves over the buildings from the front to the back. The light still comes in the windows, but it comes through reflection by bouncing off the windows on the other side of the street or off the opposite building because most of those buildings were made of light limestone. So I recreated all of those aspects by using those big lights outside, and taking all those elements into consideration.

The visual approach is also very much influenced by Maria’s dramatic life.

Yes, as I mentioned, it’s like a moving proscenium. For me, the aim is really an opera about Maria Callas rather than a biopic. It’s as if we made an opera because her life was really a summation of all the tragedies she lived through in her operas. She even said, “My mind is a stage, and my soul is the opera.” She saw herself as living in an opera, in a way, to save herself, and when she lost her voice, she lost her will to be able to endure or fight her personal suffering. She never obtained in her personal life what she did in her public life through the adoration and love that she felt from her fan base. Another aspect of the visual approach was the many elements, like the setting, props, and wardrobe, which were all a bit mannered and theatrical, and so I played with the light that way. I used warm colors and tones for her interiors, and then greens and blues coming from outside, and the greens and blues are always fighting against the warmth. She was hiding, in a way, against the cool tones.

There’s definitely an emotional component there in terms of leveraging color.

Artists, from Goethe in 1810 to Joseph Albers in 1963, have always understood that color affects the viewer psychologically. Cool colors like green are more restful, that’s why hospitals usually use greens and blues. Restaurants are painted in warmer colors to help people with their appetite. So I try to use color not only as a decorative element but also to affect the viewer emotionally, and I did that in Maria. Rarely do I get to do that. I did it in Far From Heaven, where I had Sirk as inspiration and Todd’s background in semiotics, which meant he totally got it.

One of the most dramatic and memorable scenes was the Madam Butterfly performance outside in the rain, which is clearly something going on, at least in part, inside her head. What were some considerations that went into that?

Actually, the night before, I thought about the fact that I might need the crane we’d just used, and couldn’t remember if I’d have the use of it again. Sure enough, it turned out they had sent it back. So we spent all day working to get the crane back in time, and by the time it got there, it was perfect. There were lights there because that building was an electric water facility, and there was a heavy glass enclosure over the doors, so I had a lot of lights bouncing there, giving a little texture. Then I had the one big light on the crane, which worked out exactly right. It also helped with the rain so that you could see the rain better.

Maria is playing in select theaters as of November 27th, and will stream on Netflix starting December 11th.

For more on Maria, check out our interview with costume designer Massimo Cantini Parrini.

Featured image: MARIA. Angelina Jolie as Maria Callas in Maria. Cr. Pablo Larraín/Netflix © 2024.