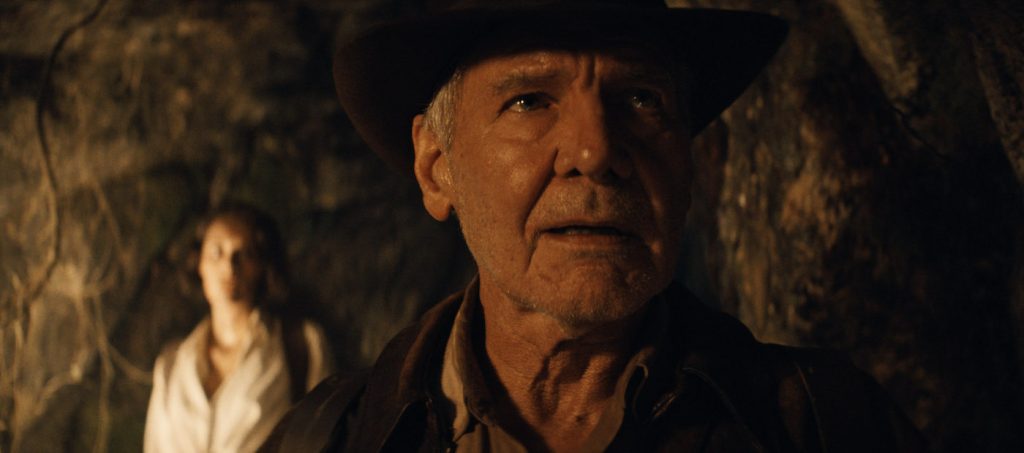

“Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny” VFX Artists on De-Aging Indy

Brad Pitt did it. Robert DeNiro did it. Samuel Jackson, Jeff Bridges, and Will Smith did it, too. Now, 80-year-old Harrison Ford has embraced digital de-aging in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (in theaters now) so he can fight Nazis looking like a 37-year-old version of his iconic action hero. Ford’s cinematic rejuvenation owes a considerable debt to ILM’s VFX artist lead Robert Weaver (Star Trek Into Darkness, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince) and Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor Andrew Whitehurst (Skyfall, Ex Machina). Working with director James Mangold, they shaped the film’s 25-minute “prologue” featuring Harrison’s whip-wielding archaeologist as he appeared in the 1981-1989 Indiana Jones trilogy.

Speaking from separate offices, Weaver and Whitehurst pulled back the curtain on “Face Finder,” machine learning, and the “ground truth” that inspired Dial of Destiny‘s VFX achievement.

Most of the movie takes place in 1969, but the first twenty-five minutes of this movie happen during World War II with Harrison Ford as a much younger man. How the heck did you do that?

Andrew Whitehurst: We used every trick at our disposal. The two key components were one, having Harrison Ford drive the performance. And the other is having artists who were furnished with the [right] tools.

How do you organize these tools?

Whitehurst: We have an overall system, which is Face Off. It’s a variety of technologies that allow the artist to pick components from each of them to combine for a single unified result.

What visual assets were available to the Face Off system?

Whitehurst: We had the first three Indy movies from Lucasfilm that we leaned into very heavily. It was high res, high-quality material, so we scanned all of that and pulled from it. Lucasfilm also has some amazing eight-by-ten still portraits done for Raiders that enabled us to get accurate references for pore-level detail. From 80s movies, you just don’t get [that detail] from cinematography because it just ain’t there. We used that for reference as much as we could because any time we can refer back to a “ground truth,” that’s always useful.

Ground truth?

Whitehurst: Yes. Material of what Harrison Ford actually looked like at the age he’s supposed to be in the film — that’s what we refer to as our ground truth.

Robert Weaver: We have a tool we call Face Finder, which takes every frame of the current shot and pulls from a repository the best likeness and performance for that individual frame.

How does Face Finder do that?

Weaver: It finds similar angles and lighting and, most importantly, the facial performance that matches most closely to the shot. The artists then have this perfect palette so they can say, “Okay, I think this [reference] works best for when Indiana Jones has a wry smile, with the way the muscles are moving.” It’s incredibly helpful.

Whitehurst: It’s also incredibly useful to have this reference material when you’re talking to Jim [Mangold] or Robert about the shot because rather than trying to describe Indy’s nose or the way that this part of his cheek has a little bit more of a crease in it, we can actually [see it and] know that we’re literally talking about the same thing. Honestly, half the battle in doing visual effects is the communications side of it. You want everybody to understand what they’re looking at.

So you have this “ground truth” of stills and scanned film imagery from the old Indiana Jones movies on one side of the equation. The other side would be current footage of 80-year Harrison Ford. Where did they film the de-aged chapter of the story?

Whitehurst: They shot on location at the [Bamburgh] Castle [in northern England] and filmed on blue screen and sound stages at Pinewood [Studios.]

And how did that footage get processed?

Whitehurst: We had additional cameras attached to the main camera, which gave us extra angles on the face. That [footage] was very useful for constructing 3D models of Harrison’s face. We also did lighting reference photography after every setup and scanned every set, so we had a 3D representation of every single take and every single environment. That was passed to ILM so they could then start working up the shots.

SPOILER ALERT: Young Indiana Jones jumps onto a train, kills a Nazi officer, changes into his uniform, and walks into the car full of German soldiers, his youthful face front and center the whole time. Just to be clear, Harrison Ford is the foundation for all that?

Whitehurst: Well, he’s the foundation for absolutely everything. The physicality is Harrison. He’s in amazing shape. He can just do it. The facial performance is entirely his. We are basically figuring out how to take what Harrison has done and then make that into something that is 1944-era Indiana Jones.

When the film leaps ahead to 1969, Harrison Ford’s tromping around in his boxers, looking closer to his actual age. It’s quite a contrast to his earlier “self.”

Weaver: I think that’s a credit to Harrison’s acting ability. He was able to change performance and spruce himself up for the younger version. We were very fortunate in that regard.

Circling back to Indiana Jones’ de-aged face, can you elaborate on some of the tools you used to shave 40 years off Harrison Ford’s appearance?

Weaver: Well, it starts with building a CG asset and capturing his facial performance as it goes through extreme emotions. Artists then do in-between blend-shapes to transition from one [raw footage shot] to the other [CG asset]. That’s the present day. Then we attempt to make a younger version of that.

Whitehurst: What goes along with building that CG asset is heaps and heaps of very talented artists who inject textural qualities and figure out how the face moves in ways that are very idiosyncratic to Indy. Additionally, we have advances in machine learning that help drive the performance level.

Weaver: We got into keyframe animation as well.

Can you give an example of how machine learning aided the process?

Whitehurst: Machine learning enabled us to do a first pass low-resolution face swap on the dailies so that when [editor] Mike McCusker could cut that [low-res sequence] rather than having to start off the raw photography. Using face-swapped footage, albeit in a rudimentary way, allowed us to get great notes from Jim and Mike.

So the machine learning enabled a sort of rough draft that saves you time?

Whitehurst: I’m not sure if it saves you time. It enables you to make better decisions about the direction you want to go in. The amount of labor involved is enormous, so being able to have conversations during the early edit about performance with something concrete is much better than having to rely on imagination until they see a first pass later on down the line. So machine learning is not a time-saving tool. It’s a helping-us-make-better-choices tool.

You guys spent three years creating visual effects for Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. What did you feel when you saw the finished cut?

Weaver: A tremendous sense of pride

Whitehurst: I would second that. It was a privilege to work with such talented people in the service of a film featuring a character we’ve loved for decades, a character who’s inspired such deep passion and fondness. When you say “Indiana Jones,” people’s faces light up — my face lights up — so to be involved in this was an absolute treat.

For more on Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, check out these stories:

“Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny” DP Phedon Papamichael on Capturing That Iconic Indy Look

Featured image: Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) in Lucasfilm’s IJ5. ©2022 Lucasfilm Ltd. TM. All Rights Reserved.