Chatting With Kent Jones About his HBO Documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut

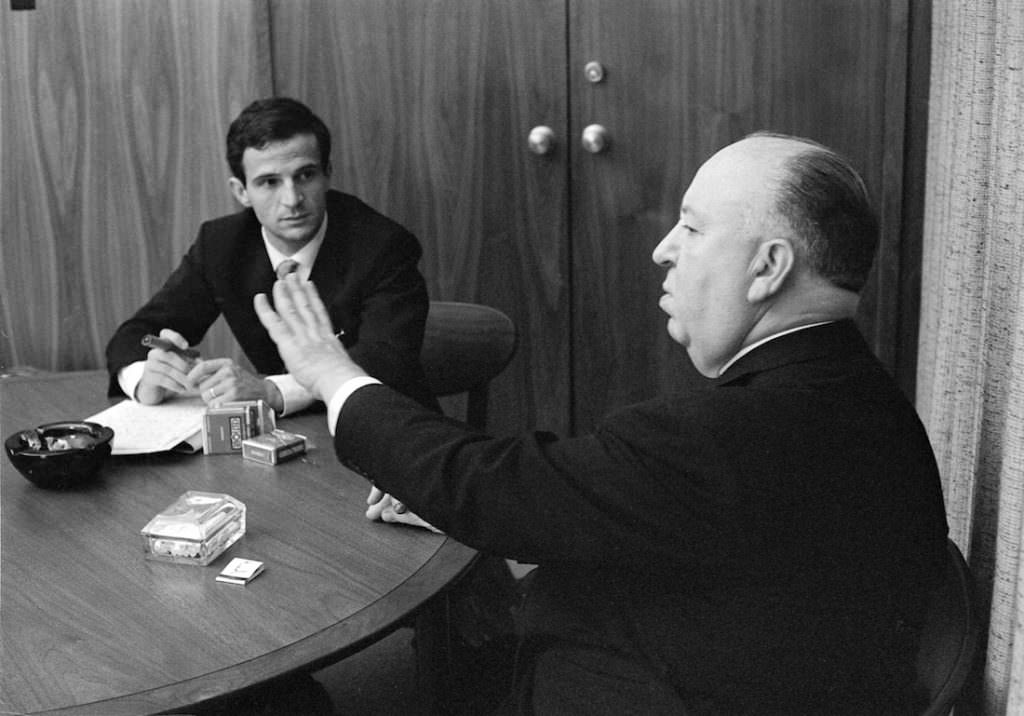

Airing Monday, August 8 on HBO, director Kent Jones’ documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut reveals the archival footage behind the titular directors’ legendary, weeklong series of interviews in Hollywood in 1962. A young Truffaut, who had only recently transformed his own career from film critic to filmmaker, traveled to Los Angeles to interview Alfred Hitchcock. He idolized the director, but at the time, Hitchock was widely perceived more as a popular entertainer than the visionary he is considered today. Truffaut helped to change the perception of the older auteur’s work, immortalizing their week of talks in the 1966 book “Hitchcock.”

The account of their interviews became — and remains — a sort of director’s bible. Hitchcock/Truffaut unveils rarely seen video footage of the two men’s talks, interspersed with conversations with various contemporary directors, from Wes Anderson to David Fincher to Olivier Assayas, on the influence “Hitchock” has had on their careers. Though slightly one-note in its contemporary subjects, the documentary offers layers of insight into a rarely seen discussion of the creative process and, of course, incredible vintage footage of two giants of 20th century filmmaking that anyone with even a passing interest in cinema would be remiss not to see. We asked director Jones about his access to this unique archive and the contemporary auteurs offering their own input:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sk-Flz37egE

Obviously the series of Truffaut-Hitchcock interviews are quite an inspiration to filmmakers across the board. Was it solely the unique quality of their existence that inspired this documentary, or something beyond?

Just the interviews—I was asked if I wanted to make a film based on the tapes and I jumped at it. But I realize now that I was also invested in making a film that stood up for the art of cinema. I think that Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow had a similar experience with their movie abbot Brian De Palma, which I love: they began by making a film about their friend, a filmmaker they both admired, and they wound up with a movie that stood up for cinema.

What was the source of the archival interview footage of Hitchcock and Truffaut’s meeting? Can that be viewed or heard elsewhere?

There are over 27 hours of tapes altogether. One set is in Paris at the Cinémathèque Française and the other set is in L.A. at the Academy. A few years back, there were segments of the conversation edited and broadcast in installments on French radio, so about eleven and a half hours can be easily found on the Internet.

How did you put together the list of directors you interviewed to contribute their opinions to the documentary?

I wanted people who a) knew the book, b) knew Hitchcock’s work, c) were invested in transmitting their knowledge of history and their experience-based knowledge of their craft, d) could think and speak extemporaneously and passionately and were uninterested in reciting freeze-dried pronouncements and proclamations, and e) were great filmmakers. In many cases, these are people I know. I’ve known Olivier for many years now, and Arnaud as well. And Marty and I have known and worked together for 25 years now. In many cases, the on-camera conversation is just an extension of an ongoing conversation off camera.

Can you elaborate on Bob Balaban as the narrator? He does have a very soothing voice.

Early on, I thought about what kind of movie I wanted to make. And I decided that since this was a conversation between two filmmakers about filmmaking, I would extend the conversation and open it up to more filmmakers. No experts or biographers, no actors or technicians—just filmmakers.

Originally, I didn’t want any narration. But I also wanted to ground and orient the audience. And we decided that having a minimal amount of narration at both ends of the movie would simplify matters. When the time came to decide on a voice, I thought of Bob. I like the tone of his voice, he knew Truffaut very well (they became friends when they were making Close Encounters), and he himself is a director.

Given the influence they’ve had on your career, what are your own favorite, or most personally influential, Truffaut and Hitchcock films?

Truffaut is a much more mysterious and unusual filmmaker than we realized back in his heyday. His films become more impressive each time I go back to them, but they also become more disquieting. It’s a very impressive body of work. The 400 Blows, Shoot the Piano Player, Jules and Jim, The Soft Skin, Mississippi Mermaid, Two English Girls, The Wild Child, The Story of Adèle H., The Last Metro—remarkable films. And then, when you get into work like The Green Room and The Woman Next Door, you’re into deeply disturbing territory. I will say that I think Fahrenheit 451 is a very special, deeply moving film. It’s the first of his movies that I saw, because it played a lot on American television in the 70s. I’ve seen it many times over the years and it never fails to move me. In this climate, with Donald Trump, a guy who seems like he gets bored reading street signs let alone books, actually running for president, the movie acquires a whole new level of urgency.

As for Hitchcock, the last time I was asked by Sight and Sound to do my ten best of all time list, I put Notorious on there. Five minutes later and it might have been Vertigo or Rear Window. But in fact, it’s the entire body of work that I love. It’s an enormous one – 52 surviving features, many TV episodes, two wartime medium length films, a German version of Murder, and a section of an omnibus film. And the fact is that not one film is made in second gear. You can’t say that of any other director working during the studio era. Of the people working at his level that started during the silent era—Ford, Hawks, Lubitsch—there are the odd titles here and there that are tossed off. Not true of Hitchcock. You might not like Juno and the Paycock or Champagne or Topaz, but they’re not tossed off. The Paradine Case is, to my mind, not so satisfying, but I think it’s more attributable to the interference of the producer (Selznick) than to Hitchcock. So I go back to Hitchcock a lot, to the great films and the minor films and the flawed films, and they all surprise me every time and the dialogue between them becomes richer and richer. Only Ozu has a body of work that’s comparable.