“The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey” DP Shawn Peters on Lensing Samuel L. Jackson’s Rare TV Performance

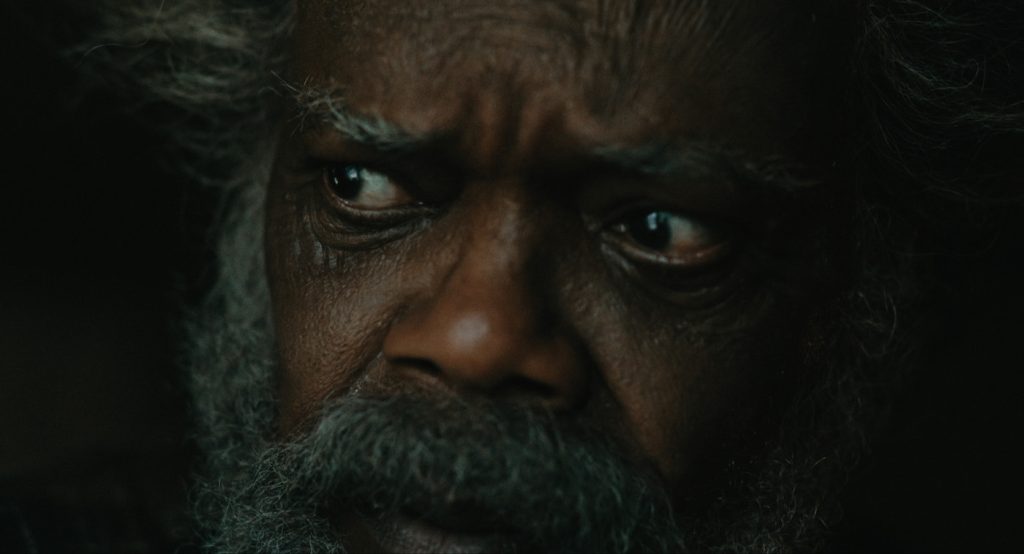

Based on Walter Mosley’s eponymous novel, The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey portrays 91-year-old Ptolemy (Samuel L. Jackson), a lonely widower suffering from Alzheimer’s, as he undergoes a transformation thanks to Robyn (Dominique Fishback), the teenage daughter of a family member’s friend, and an experimental new drug, offered at a beyond questionable clinic.

Jackson, who rarely takes on television projects, is sublime as the limited series’ Papa Grey: by turns helpless, vulnerable, determined, and all-knowing. The Alzheimer’s drug proffered by the unsettling Dr. Rubin (Walton Goggins) doesn’t just restore patients’ memories, it fills them in entirely, down to everything they’ve ever eaten and every place they’ve ever been. Ptolemy’s returned memories take him back to the 1930s, to his childhood and the tragic history of a beloved uncle, Coydog (Damon Gupton), and to the 1970s and 80s, during his courtship and marriage to Sensia (Cynthia Kaye McWilliams) an occasionally stormy but loving affair.

Ptolemy’s restored decades-old memories of Coydog set him on a mysterious hunt for, well, something that seems to promise to greatly impact his present, but it’s teenaged Robyn who brings the change to Ptolemy’s life that matters most. Adrift and initially reluctant, she winds up moving in with Papa Grey, de-hoarding and cleaning up his Atlanta apartment and setting his experimental Alzheimer’s treatment in motion. Ptolemy’s memories come back, and we learn what a full life he once lived in tandem with witnessing his return to the world of the living in the here and now, thanks to the platonic mutual adoration that wells up between the old man and his teenage caretaker.

Warmth returns to Ptolemy’s once bleak home, where much of the action, past and present, is set. And as Ptolemy regains his lucidity, focus returns, both to his own world and in-camera. We had the chance to speak with cinematographer Shawn Peters (who split the series’ six episodes with Hilda Mercado) about how he conveyed Ptolemy’s initial dementia via the camera, visually separated the show’s period flashbacks, and of course, how the rarified experience of working with Samuel L. Jackson played out on set.

Was there either a particular setting or time period that you started with in terms of determining how the series, overall, would look?

The first episode, in Ptolemy’s apartment, is meant to be in the modern world. But what informed me most, aesthetically, was reading the novel before reading the screenplays. What I felt emotionally from reading about his world was also my initial gut reaction as to how to design the world, aesthetically. Because there are flashbacks to the 1930s, 1970s, and 1980s, Ramin [Bahrani, director of the series’ first episode] and I really thought deeply about how to separate those worlds, with color treatment, different lenses, different quality of lenses. We had three sets of lenses throughout the series.

Did you wind up separating the lenses by time period?

Time period and also, as his dementia waned as he got the medicine. We had one set of lenses for the first episode where he had full-on dementia. Those were a set of lenses called Falcons, from Camtec in Los Angeles. I really love those lenses for that space in his exterior and interior world, because they’re just dirtier. They’re less pristine. They’re loose, detuned a bit, and Camtec put a special coating on the lenses to distress them a bit. As Ptolemy got clear and Robyn became involved in his life, we changed the set of lenses.

What went into the process to convey, aesthetically, someone in the throes of Alzheimer’s?

For those, we used a lot of glass optics. We would sometimes put two split diopters on the top and the bottom of the lens, to blur the bottom and top and only have the center clear. We’d have one at a 45-degree angle. We used them in different ways, and that was both for when he had a vision of someone else he remembered, and sometimes we used them on him when he was in that state.

We also had one very special lens from Camtec, which was an Angenieux 50mm lens that was designed originally for surveillance, so it was a really fast lens. When you put that close to someone’s face, there’s no depth of field at all. You’re getting the front of their face really clear, and then the back completely falls off. We had that lens close to him when he was going in and out of a dementia state, to bring you inside of his world and have the background fall off. And Ramin and I talked a lot about why handheld. There were a lot of why questions. Where is Ptolemy psychologically in the space? When he was really unhinged, we went handheld. We tried to improvise internal emotion with the camera. We thought about his POV, what was on his mind, and how to use optics to show that.

There are certain spaces that are distinct and magical, like Sensia’s bedroom, which becomes Ptolemy’s room again. How did you decide to light those?

Ramin and I drilled down with the production designer [Gregory Weimerskirch] about what her world should feel like to him. For me it was really warm, most of the lighting there feels like it’s late in the day, and the wallpaper has that gold shimmer. We thought about gold and warmer sources, later afternoon light, and tungsten and sodium light later in the nighttime scenes. Even in the skin tone, we wrapped him in warmth when he was in that room.

You feel acutely aware of the time of day in this show. Was that intentional?

The main set was Ptolemy’s apartment. We designed it so that we could change the direction, we could push light in the window in the direction of the sun. We also had soft sources, so I could do something that felt like an overcast day or an afternoon sun, or obviously, an evening look. There’s one scene in the first episode where Ptolemy’s lying on that bed under the table, and we change from day to night in-shot, like a time-lapse. In his apartment, other sets too, we had full control over the time of day. So much of what we think about how we feel emotionally is what’s being given to us by the atmosphere outside our houses, where we spend so much time, as Ptolemy does in his place. Having a diversity of time in that apartment was key because that apartment was a character. It had to have an emotional arc to it.

So much of the show, there’s a focus on just Ptolemy, or him and Robyn, or at most a handful of people. As the cinematographer, how does that affect what you do?

I think just as a cinematographer in general, my goal is always to have the characters I work with, whether they’re good or bad, there’s always some human empathy. I’m always thinking about how the viewer is going to empathize with this fictional character. We did a lot of that with lensing. Even in camera testing, I wanted to know which lenses were kinder, and which angles were not so kind, for the villains and other people around. Even lighting in the eyes — the direction in which light hits the eyes creates an emotional response in the viewer to who the character is. If it’s dead in the center, it’s serious. If it’s below, it’s more kind. If it’s up, it’s more questioning. No light, there’s a darkness. We thought about those kinds of things while lighting Ptolemy’s eyes as well as other characters, as well as camera position and focal points.

Can you tell us a bit about working with Samuel L. Jackson?

Well, one, I think he’s like mensa level smart. Someone who has that much experience on set knows everybody’s job. If he sees something moving in a bit of a weird direction, he’ll point it out, because he knows my job. He’s on camera in almost every scene, and other actors, not as established as him, would flub their lines, but Sam, never. I mean, maybe one time in four months. The level of professionalism showing up in character, on and ready, was something I’d never experienced before watching an actor. It was sort of incredible for me.

How did you feel about the work as you wrapped the show?

I would just say it was really a pleasure for me to play with a character that had so much range in terms of his own emotional, internal world. Now he’s going through dementia, he has so much regret from the past, and some of that regret may have triggered that dementia. When he finally gets his memory back, not only facing the regret, the nightmares, he’s also engaging with a new young person he has to be present for. For me, it was a pleasure seeing a 90-something-year-old African-American man have that much humanity on screen. It was something that as a filmmaker, was really wonderful for me.

The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey is now streaming on Apple TV+. The final episode airs on April 8.

For more stories on Apple TV+ series and films, check these out:

“The Tragedy of Macbeth” Production Designer Stefan Dechant on Joel Coen’s Minimalist Masterpiece

Apple to Produce Adam McKay’s “Bad Blood” Starring Jennifer Lawrence

Brad Pitt & George Clooney Reuniting in Upcoming Thriller for Apple

Emmys 2021: “The Crown,” “Ted Lasso” & More Make History

Featured image: Samuel L. Jackson in “The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey,” now streaming on Apple TV+.