How the “Moonfall” VFX Team Tapped Physics to Destroy the Earth

Don’t look up! The moon is on a collision course with Earth. Filmmaker Roland Emmerich, who brought us Independence Day, The Day After Tomorrow, and 2012, returns with another global disaster movie in Moonfall (premiering February 4) that has a colossal twist. This time it’s up to NASA executive Jo Fowler (Halle Berry), astronaut Brian Harper (Patrick Wilson), and conspiracy theorist K.C. Houseman (John Bradley) to save humanity.

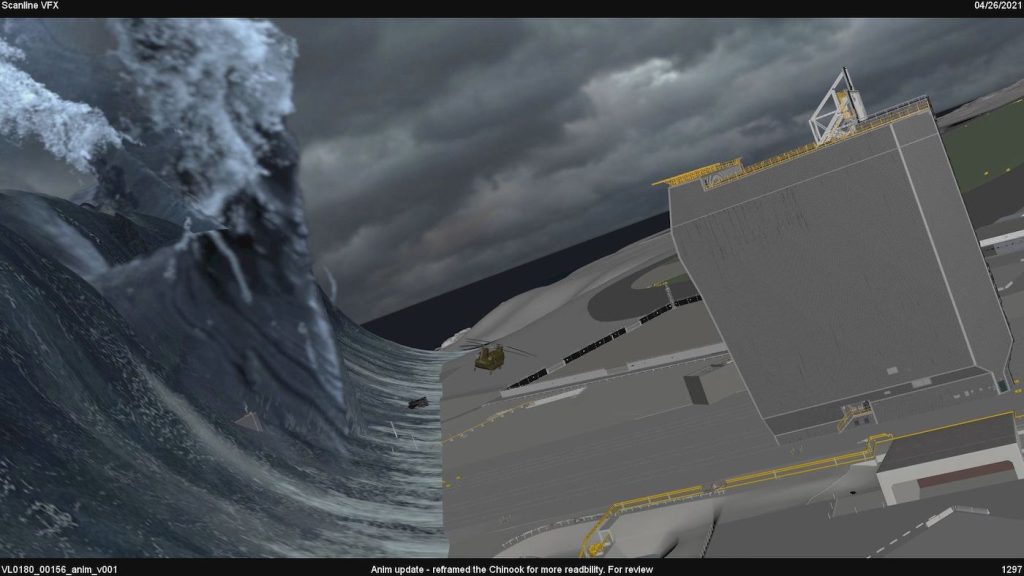

When the moon is knocked from its orbit by a mysterious life form its descent of destruction causes a number of disastrous events on our blue planet. Creating the chaos alongside Emmerich was visual effects supervisor Peter G. Travers, who with help from VFX vendors DNEG, Framestore, Pixomondo, and Scanline VFX, detailed roughly 1,700 shots for the catastrophic space odyssey.

“It takes a village to make a movie,” says Travers, who started prepping for the film shortly after Emmerich’s Midway. “Part of my job is talent recruiting and we cast this film tremendously based on the talent in Montreal. Scanline and Pixomondo took care of all the ground-based destruction, Framestore looked after space and DNEG did all the moon work.”

Travers shares with The Credits how physics grounded the collision course of these two celestial bodies and what went into destroying the planet.

Calculating Mass Destruction

The concept of the moon crashing into Earth is a supernatural phenomenon. In reality, it could never happen. The big hitch with the idea is a matter of physics. The moon simply doesn’t have enough mass for it to happen. It would be like dropping a ping pong ball into a high-powered fan. It would float away rather than simply crash. But that didn’t stop Travers from trying to figure out if it could.

“We did a simulation in Maya, and what people may not realize who use the 3D software for visual effects, is that at its core it’s a physics simulator. I built a model of the solar system and had the moon orbiting the Earth based on Newtonian physics. Roland gave some stipulations that he wanted it to take place over three weeks and for the moon to orbit several times before crashing into the Earth. I built a mini simulation and started messing around with the moon. I came to the quick realization that if we inject the moon with more mass than it currently has, it gave us purpose for the anomaly.” [aka the mysterious life form]

Travers also found out that adding mass to the moon had gravitational effects. “The moon as it currently stands is 1/100 the mass of Earth. We injected an incredible amount of mass into the moon and made it 1/3 the mass of the Earth. Due to the gravitational equation, if the moon has 1/3 the mass of the Earth, and the two were touching, the moon would be pulling you much stronger than the Earth.” It meant, not only would the moon be pulling you sideways but the Earth would be pulling you down.

“The simulation killed two birds with one stone. The anomaly can make the moon heavier and we can have the moon fall, and then it also gave us these severe gravitational pulls on Earth,” says Travers.

A Monstrous Anomaly

The villain in the story is the particle-like swarm that threatens humanity. We first encounter the shadowy monster in the opening scene of the movie when it crashes through a spaceship Brian and Jo are performing maintenance on causing it to spin out of control. It later resurfaces in a more threatening manner as our heroes try to save the world. Visual effects brought it to life with grounded intention.

“The anomaly is based on mathematics. It started out with Roland showing me an animated Mandelbulb, which is a 3D animated plot of a fractal equation,” says Travers. [similar to this one here]

From there, visual effects crafted its movement, size, and shape based on its actions in each scene. Certain sequences have the creature flying through space, zipping in tunnels and crushing spaceships or attacking people with long tentacle-like arms. When the monster changes shape, VFX maintained the mathematical characteristics to create the new form.

“It’s artificial intelligence, so when its limbs would protrude out, we always tried to make it have a certain level of symmetry. If it needed to grow an arm out of its left side, it also did out of the right side. It does get a little chaotic at the end, but within that, it’s a chaotic form of mathematics,” Travers notes.

To keep the mysteriousness, Travers points out Emmerich was “extremely careful” in what he wanted to show early on. Then as the story unfolds, more of the menacing figure takes shape before ultimately revealing itself in a climactic scene.

Destroying the Earth

With the moon’s looming impact there are a number of catastrophic events that unfold. We see entire cities crumble, mass destruction and the moon breaking apart into fiery rocks that plummet to the earth. In one scene, the ocean generates giant “gravity waves” as tall as skyscrapers which crash down on our characters. In another car chase sequence through Aspen vehicles are lifted from the ground, smashing into each other all a result of the gravitational pulls.

Visual effects grounded the aesthetics based on their research with some wiggle room to heighten the drama. “There’s always a certain element of cinematic impact. If it looks cool we do it that way but we tried to stay disciplined within the physics. If the math supports what we are doing, it’s a win-win.”

Those epic shots are all manageable because of a huge creative team. “I have to thank the around 600 artists that worked on the film. With these big shots you need a ton of detail so they are pretty painstaking. Every little detail or tree flying in the scene are all modeled. The effects animation work is one of the more difficult departments within an effects pipeline. It takes a tremendous amount of iterations to make that work. It takes talent.”

Filling the Void

While shooting scenes inside spaceships, rather than relying solely on bluescreen and filling in the environments after the fact, production shot using LED panels that displayed scene-specific content. Not only did this simulate a real-world setting for the actors but the panels provided natural light and reflections inside the crafts that can be more difficult to replicate in post.

“We had LED panels around 16 x 9,’ on cranes, bouncing them around and angling them to optimize the shot,” says Travers. “Cinematographer Robby Baumgartner and I had one day to experiment with them to see what we could with the brightness and lighting. They became incredibly advantageous when we had radical lighting conditions inside the capsule, in particular the opening sequence where the shuttle is spinning rapidly.”

To pull the scene off the team blanketed the shuttle with LED panels and had a sun fly across the displays. The speed, control and brightens of the sun were all controlled in Maya within their pipeline.

In other scenes, the LEDs showed up on camera. “During the Vandenberg launch, what you’re seeing is the existing photography that we displayed onto the LED panels. The crowds going by and the shuttle shooting up into the atmosphere are all images of the LED panels directly from out the window.”

Looking back Travers says, “I really think the timing and the message the movie delivers is good. Covid gave us this great pause and reflective moment, certainly in my life. It’s a ‘what-if’ movie that makes you realize how good we have it on this planet and all it would take is a slight nudge to change everything.”

Featured image: The Endeavor Space Shuttle docking at the International Space Station while the moon hurtles towards Earth in “Moonfall.” Courtesy Lionsgate.