Talking to Bryan Cranston & Director Jay Roach About Trumbo

Blacklisted in 1950s Hollywood for having been a member of the Communist Party, screenwriter Dalton Trumbo continued to do what he did best: write scripts. He just couldn't do that under his own name, even when he penned two Oscar-winning movies, Roman Holiday and The Brave One. This period in the writer's life is the subject of Trumbo, directed by Jay Roach and with Breaking Bad star Bryan Cranston in the title role. (The movie opened in New York and Los Angeles on Nov. 6, and will go wider on Nov. 13.) The cast includes John Goodman, Diane Lane, Louis C.K. and, as perhaps Trumbo's greatest adversary, Helen Mirren. She plays Hedda Hopper, a gossip columnist who doubled as a stalwart anti-Communist.

Roach and Cranston recently traveled to Washington, where Trumbo tangled with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1947, leading to an 11-month prison sentence for contempt of Congress and the ban on work by the so-called Hollywood 10. While in D.C., the director and actor talked to The Credits about Trumbo the movie and Trumbo the man. Their remarks, which have been edited for length and clarity, began with a discussion of what drew them to the project.

Roach: For me, it was this man and his talent. I loved those movies. I grew up watching Spartacus and reruns of movies like Roman Holiday and 30 Seconds Over Tokyo. I hadn't seen The Brave One, which is an amazing film, and apparently it was hidden for a long time by rights issues. When I read that he wrote those movies while blacklisted, and won two Academy Awards, I was hooked. Right from that moment. "That's the guy who's the enemy of the state of 1947? That's the guy you want to shut down?"

You could tell he was such a humanist, and yes, he obviously was a communist, too. But I was in. As soon as I heard those elements at play, I was like, "OK. that's an incredible story. I want to know about it." Hopefully, that means the audience will want to know, too.

Cranston: The character was certainly a major component, but first and foremost it's always the story. You can have a great character and a bad story, and it won't add up to anything important. So the story resonated with me. The loss of civil liberties. The damage done by an overreaching branch of government that took upon itself to be judge, jury and executioner. It sent men to prison, not for committing a crime but just because it was not pleased with their cooperation, or lack thereof. Under the threat of incarceration, demanding that they withdraw their rights to free speech and free assembly. This is the cornerstone of American government and lifestyle.

It's a dark, dark period in American history. I hope that's the message, especially with younger generations. If they see the movie for whatever reasons, and are entertained, great. But even better if they walk away and go, "Wow. I'm curious to find out more about this."

Roach: All praise to our great screenwriter, John McNamara, by the way. That was the big attraction. All these things that we've been talking about were in the screenplay. It was a great screenplay about a great screenwriter. I want a T-shirt that says, "John McNamara, All Praise," because he really launched the whole thing.

Is this one of those screenplays that was knocking around for a while?

Roach: He had been working on it for quite a few years. He had optioned [Bruce Cook's 1977 biography of Trumbo] himself. Paid the option fees himself. Then a producer that we all love, Michael London, who produced Milk and other films that I loved, brought it to me. It took a couple years of more development. It all accelerated once Bryan jumped in.

One of the things that's notoriously hard to get on film is the process of writing. I guess it helps if you have a character who's known for writing in the bathtub. Were you worried about getting that internal process on the screen?

Cranston: No, I let Jay worry about that. That's truly his dilemma. To take what is a non-cinematic activity and make it cinematic. And he found a way to do it. But also, it's less about writing and more about the habits around it. We saw that he had a bad back, and that he drank and he took pills and smoked like a fiend. He's mumbling the lines, and thinking out loud, "What would a princess say?" He agonizes over every little bit, and that's part of the process of writing, too.

Roach: Also, what I was happy to have portrayed cinematically was the rewriting. Which was Bryan sitting in the bathtub, cutting it up and pasting it back together, stapling it and dropping some of it in the water.

Cranston: The first cut-and-pasting.

Roach: Exactly. I liked that we got to show the agony and ecstasy of writing.

The movie starts in the 1940s, but the bulk of it is set in 1950s Hollywood. Did you see it as a foreign country, or as someplace you recognized from your own experience?

Cranston: We were little boys in the '50s. So we had to learn the Hollywood history in retrospect. But I must admit I didn't know the extent of this. I knew about the Hollywood 10, Communists went to jail, they wrote under assumed names, and Dalton Trumbo wrote Spartacus. And then I had to really dig in. But that's the great thing about what we do. For a period of time, we get very intimate, very intense, with a subject. It's part of the joy of it, actually.

Roach: One of the fascinating things about the '50s was how complicated the politics were. The United States was allied with the Soviet Union during the war. Then after the war there's so much animosity, and in our country there's this hysteria about the genuine threat that totalitarian Communism posed. Hollywood was very divided. You had Hedda Hopper, John Wayne and Walt Disney, and Ayn Rand, who wrote the manifesto for the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. And then you had these progressive guys, a lot of whom were union guys. They were just trying to get a safe working environment, and reasonable work hours. It became a very intense left-right thing. That's hard to imagine in Hollywood now; it's not as fractious as that. It was a great learning experience for us to delve back into that battle of ideas.

Politics aside, did it seem that Hollywood sort of worked the same way in the '50s as today?

Cranston: There was a studio system back then, and the unions weren't as strong as they eventually became. The fear that permeated the country was also deeply rooted in Hollywood. All the unions turned against their members. The main responsibility that they have is to protect their membership. But the Screen Actors Guild, Director's Guild, Writer's Guild and the Motion Picture Academy all shut the door to these men and women. Let's learn from that. Let's realize that squashing any civil liberties is not a benefit. Don't be intimidated, or threatened, by someone who has a different point of view.

One thing I didn't anticipate going into this movie was that Trumbo's great antagonist would be Hedda Hopper. Is that partially the power of Helen Mirren?

Roach: No, we had the character before we had Helen. Thank God we got Helen, because she's such an amazing actress. You could portray a character like Hedda as a one-dimensional zealot — which in some ways, she was. But Helen found layers to her, and I really believed her when she said, "I would trade bringing one boy back from Korea for all these guys' careers." She meant that.

She was very much a part of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, which is who invited Congress to come to Hollywood. Congress didn't come out on its own. It was invited by people who wanted to "clean up" Hollywood. They were trying to protect the image of Hollywood, and they somehow succeeded, with her help, in convincing Americans that there was risk of being hypnotized to signing on to the Communist Manifesto through movies like Roman Holiday. [laughs] They accused Trumbo of being subversive. He did 30 Minutes Over Tokyo and A Guy Named Joe, which were patriotic films. They were war films.

She was a great propagandist who was able to sell ridiculous ideas. So I thought she was the perfect antagonist to go up against an artist who trying to just do good work.

Cranston: Had she simply stated her opinion, there could be no complaint about her actions. But she crossed the line of physically going after people, and depriving them of free speech.

Roach: And asking the government to get involved in shutting down writers.

Cranston: Shutting down. That's the problem.

This is, obviously, a movie about a '50s screenwriter. Has the role of screenwriters changed since Trumbo's days?

Roach: I think so, because of television. Bryan should talk about how it works in television.

Cranston: There's a content issue there. They need more and more content. Quicker. It gave more power to the writer. Where Trumbo took seven years, I guess, to develop. Argo, even with a guy named George Clooney behind it, took six or seven years to really get going. There's one writer, basically. Obviously, other writers can be brought on to a film. But in television there are many writers. A lot more writers are needed.

But storytelling is storytelling.

Roach: It is curious to me how it's evolved so differently in the two media. In television, you have to feed the beast, and the director's not going to feed it fast enough. I love what Vince Gilligan did in Breaking Bad. I love what Matthew Weiner did with Mad Men, what David Benioiff and D.B. Weiss did with Game of Thrones. They're the auteurs of those. They direct the directors.

I'm a director, and I like working as a collaborator. In film, I can just say, "You don't need to come to the set today. I'll take care of it." But I have the writers there all the time. I wish there was a little more respect for writers in features. It hasn't really changed that much, even since the '40s.

Did this seem an apt time, politically, to make this movie?

Roach: For me, it's always apt. There's a certain timelessness, because it's a pattern that recurs in history of using fear of a real external threat to get a small population that has very little to do with the external threat to conform to your political ideals. People make names for themselves doing it. Richard Nixon started in HUAC. That was one of his first moments in the spotlight. It seems like we should never forget this story. We should continue to revisit it as a cautionary tale.

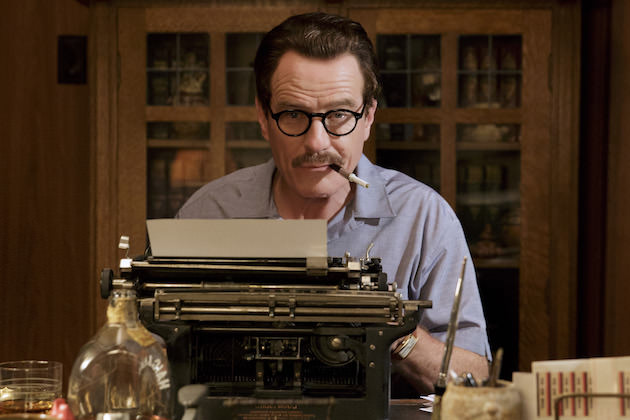

Featured image: Director Jay Roach (left) and actor Bryan Cranston (Dalton Trumbo, right) discuss a scene on the set of TRUMBO. Photo by Hillary Brown Gayle. Courtesy Bleecker Street