“Minari” Editor Harry Yoon on Shaping the Film He Was “Born to Edit”

Minari is a moving portrait of a young family setting out on a new life in the Ozarks. It will invite you in with its photography (the work of Lachlan Milne) and production design (by Yong Ok Lee), pull at your heartstrings with its “sensitive and uplifting” score, and keep you wholly absorbed in the world of the Yis thanks to masterful editing by Harry Yoon.

Yoon spoke to us about how he approached cutting this film, whose screenplay draws heavily from the childhood memories of director Lee Isaac Chung, who grew up in rural Arkansas during the 1980s. Like Chung, Yoon is the son of Korean immigrants and grew up in California around the same time. His intimacy with the cultures, landscapes, and languages of two countries — as well as the spaces in between — is a boon to the project. It translates into sensitivity and precision, palpable in every scene.

Yoon, along with other department heads, worked hard to “get it right” when it came to capturing the particulars of the Yi family’s story, which often required drawing on their own memories and experiences. The result is a triumph of a film that speaks to the joy, sorrow, and even comedy of chasing the American Dream.

Editing an editor is no easy feat, but we present to you an abridged Q&A with Harry Yoon about how he came to be involved in Minari, an alternate ending that just wasn’t meant to be, and the magic that keeps him enamored with his job.

What were your early conversations like with director Lee Isaac Chung? How did you guys work together?

What was great about working with Isaac was that, from the very beginning, he was very collaborative. He was open to notes and really sought my ideas and thoughts on what was working and maybe not working in the script. And so we kind of dove right in. Sometimes when you speak to a director, particularly a writer-director, you know they appreciate your notes, but you don’t necessarily see them incorporating them because they’ve got a thousand other things to think about as they head towards casting and pre-production. But Isaac was very interactive, very receptive, and actually started making changes to the script based upon the conversations we had.

Do you remember any of those script suggestions, big or small?

We talked about certain concerns that I had about an ending for the script that was more of an epilogue — so, it actually jumped forward in time by several years. We re-met the characters, David and his sister, when they were in junior high school or high school, and they were visiting Youn Yuh-jung’s character in a convalescent hospital. It was a lovely ending, but my biggest concern was that we’ve kind of fallen in love with and identified with these children. They’ve been our points of contact and identification through the film, and I wondered if we see a whole new set of actors, even though we intellectually know who these people are, I don’t know if we’ll have the same kind of emotional response.

So what was the solution?

We talked about something more open-ended, an ending that didn’t lose that emotional thread that we have with these performers. And he [Isaac] came up with something literally overnight, and it just blew me away for a couple of reasons. One, that he would even consider changing something as important as the ending while in pre-production — they were already casting the other actors. And two, what he wrote was just so perfect. It’s a jewel of a scene. So, I was just really, really impressed with his openness to collaboration but also his remarkable talent.

How did you prepare for this project, if you needed to prepare at all, considering the personal connection you felt with the script?

I feel like I was kind of born to make this film. It speaks so much to not only my experience as an immigrant in America with parents who struggled in their efforts to achieve the American Dream through small businesses and entrepreneurship but also to my experiences specifically as a Korean American. As it is for so many of the Korean American department heads who worked on this film, this is a mirror of our childhood or moments in our childhood. Isaac’s writing and his pure curation of memories were so specific and so true that they were like little explosions of memory for all of us. I think sometimes, especially if you’re working in fantasy or science fiction, it’s your imagination that leads you to your true north. Here, for me, it was very much my life, my life experiences.

The scenes are just so beautiful — they flow so elegantly. What was your approach to editing like? Were there any sequences that you had to revisit over and over again, or were there any that came together without so much toil?

I think the real work on this film was the construction of a film in which every sequence felt essential. This is a film in which time is a little bit elliptical — the timeline isn’t absolutely clear. So, it’s very easy to get caught lingering in places that aren’t necessarily telling you something new, either emotionally or about the characters or about the story of this family. Also, we wanted to try to create a portrait of a family. So with those considerations in mind, I think the hard work of the film was in crafting something where every scene, every moment, felt essential.

Was there any shot or sequence that stood out for you?

Even though we got rid of a lot of different scenes, there were also shots and beats that were actually unscripted that ended up being really important, pivot points editorially. One shot in particular is this really beautiful shot at dusk of Steven Yeun’s character just smoking out in the field. And that was a total accidental shot. Lachlan Milne, our amazing cinematographer, was out shooting some landscapes at dusk as they were waiting to finish the day. Steven just walked up in costume, and they just went along with it. A shot like that can play a role at different points in the film, but where we ended up using it was at this pivotal point where he realizes he’s reaching a kind of breaking point with how things are going. And so I think part of the challenge was in deciding where we place these elements. What feels essential, what doesn’t feel essential?

Does that work of whittling down ever leave you with a sense of loss? Is it painful to you on an emotional level or just part of the job?

I think they’re less painful when you see the results. I think if that decision is being imposed by, let’s say a commercial mandate that the film be a certain length and you know that the film is less than as a result — that’s one thing. But I think if the results feel more muscular, if you remove a scene and the juxtaposition of what’s left ends up being beautiful or meaningful, then I think it’s hard to mourn since that’s just the process. As you edit more, you realize that everything is on the table and everything should be tried because that’s the gift of the process. You can have happy accidents as a result of lifting things, moving things. I think that’s what gives you a sense of like, hey, there’s still magic in this process. It’s nice when your work surprises you. It’s why I love being an editor.

Director Lee Isaac Chung

Credit: Josh Ethan Johnson

You and I actually went to the same liberal arts college — and I know there’s no official film program. Becoming a film and television editor must have been a somewhat self-directed journey. What was your parents’ response to your choice of career?

I think they already had the sense that I was a Korean kid that made unusual decisions. They saw me grow up and ever since elementary school, I was performing in school musicals and plays and things like that. So, I think they knew that I gravitated toward the arts. But at the same time, because I was the first son of an immigrant family, I approached this decision to fully commit to a career in the arts with a tremendous amount of ambivalence. In fact, I took all the way to the age of 30 before I finally full-on committed. When 9/11 happened, it was a wake-up call. I was like, wait, we only have one life and I think I will regret it forever if I don’t make this decision. I think by that time, my parents had seen that I was responsible — it wasn’t a spontaneous decision. They saw I had a game plan and they blessed my decision to sell everything and then start over at the age of thirty-one in Los Angeles.

Years later, I had a conversation with my dad. I asked ‘Why did you say yes to that decision? Why did you bless the decision?’ And he said, ‘When I moved to the States, it wasn’t just so that you would have financial security, the way other parents hope for, which is why they push their children into law or medicine. The primary reason I wanted to come here was so that you’d have the freedom to choose what you wanted to do because that’s not something that I had growing up.’ I was really moved by that answer. In the end, I think that’s what won out over their concerns, that desire for me to have the freedom to choose my path.

In making this film, what an incredible way to honor him and your mother and really all parents who do what they need to do to make a life for themselves and their kids.

That’s why this film is like a dream come true. I told my wife, I was like, you know, Jane, if I don’t get to work on anything else, like, it may have been worth it.

Minari was released in theaters in the United States on February 12 and will be available via streaming on February 26.

For more on Minari, check out these interviews:

Yuh-jung Youn on Creating Family in “Minari”

Composer Emile Mosseri on Scoring for Family Dynamics in “Minari”

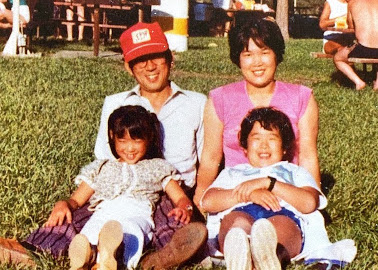

Featured image: Alan S. Kim, Steven Yeun, Noel Cho, Yeri Han. Credit: David Bornfriend/A24