Writer/Director Tiller Russell on his Real-Life Crime Drama “Silk Road”

Writer/director Tiller Russell was ideally suited to take on the crime thriller Silk Road. As the director of The Last Narc and Netflix’s Night Stalker: The Hunt for a Serial Killer, Russell is no stranger to looking squarely at the darker corners of the human soul. For Silk Road, which was inspired by David Kushner’s Rolling Stone article “Dead End on Silk Road: Internet Crime Kingpin Ross Ulbricht’s Big Fall,” Tiller found himself digging into one of the wildest criminal cases of the last few years, and arguably one of the most brazen attempts to bootstrap the internet into the foundation of an international criminal enterprise in history.

“As someone who goes back and forth between nonfiction and narrative work, it’s a careful calculation,” Tiller says about adapting Kushner’s article into his ripping narrative feature. “I began this with the rigorous, journalistic prep, as if I was making a doc series. I pulled every court filing, I had Ross’s girlfriend as a script consultant, I had the narrative constructed by law enforcement, the US Attorney, DEA, Treasury, there was this vast historical archive from which to work.”

If you’re not familiar with Ross Ulbricht and Silk Road, here’s a brief primer. Ulbricht created, essentially, an Amazon for drugs, where buyers and dealers could connect in an invisible, unregulated marketplace on the darknet. Whether you wanted pharmaceutical-grade cocaine or high-octane cannabis, Silk Road was where you could go to have your drug of choice delivered to your door—by the U.S. Postal Service. At the height of Silk Road’s operation (it only lasted for two years), all that was known about its creator was his moniker, the Dread Pirate Roberts, a name lifted from The Princess Bride, of all films. No one yet knew that the Dread Pirate Roberts was a 26-year-old kid from Austin, Texas, who believed his darknet drug ring was a righteous blow against the system. Ulbricht wasn’t alone in believing the internet’s potential and promise had been commoditized and lobotomized, and what it needed was a place that was actually free. Yet what he created ultimately had little to do with freedom and a whole lot to do with money.

“What’s interesting to me is here’s this young guy who starts out as a dreamer and wants to change the world, and who in the course of 18-months has this meteoric ascendancy and metamorphosis from dreamer to gangster to legend,” Tiller says. Tiller dug into Ulbricht’s diaries on his laptop and his public postings under his pseudonym. “So there was access to his voice in a fundamental documentary way. And 99.99% of the voiceover is all drawn from that. My editor and I sifted through all that material so it would hew very closely to who he was.”

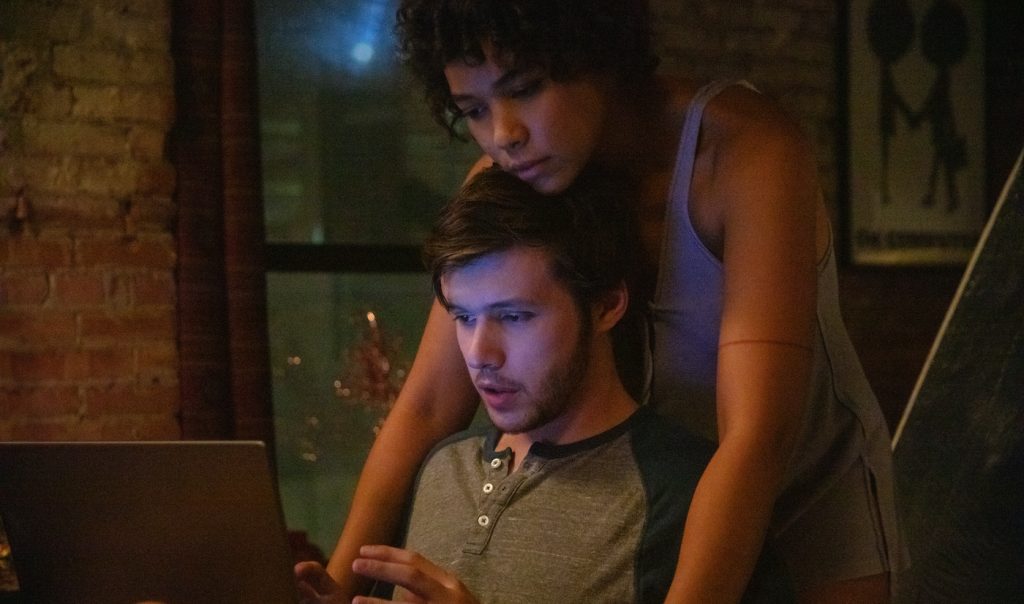

Ulbricht is played by Nick Robinson (Love, Simon), whose performance as the idealist turned international criminal is one of the two fulcrums around which the film turns. The second is Rick Bowden (Jason Clarke), the Baltimore DEA agent hunting Ulbricht, and far from a saint himself. “The cat and mouse dynamic between them give you a natural propulsive drama,” Tiller says. “The film is a two-hander, a collision course between two men, these two exact wrong people who are like missiles fired right at one another.”

Piecing together a narrative feature out of the Byzantine nature of Ulbricht’s rise and fall was no easy task. “I didn’t have Ross as a source, a subject, or a consultant, and I had all of these conflicting accounts,” he says. “I had law enforcement’s version and the family’s version from David’s brilliant Rolling Stone piece. So from these conflicting narratives, my goal was to triangulate it.”

Here’s where Tiller made an intriguing choice—he took the overwhelming amount of reportage, done by Kushner, law enforcement, and his own work, metabolized it, and then tried to forget it.

“I felt like after doing all this research I’m going to throw it all away and be in the shoes of Ross Ulricht and Bowden,” he says. “I needed to understand it from the inside, the feeling of lying to certain people, the feeling of burning with ambition or fear or arrogance. So to fill those gaps in the historical record, I wanted to make something that was really personal and evocative. Human truth as I know it. So it was using parts of myself and my psyche to fill that in, while still being spiritually true to the characters.”

Ulbricht’s path from idealist to wanted criminal also charts, in a way, the rise of the internet from a tool to an all-encompassing, nearly all-consuming medium for going about one’s life. “It’s such a weird transformation culturally and globally that all of this tech has wrought for us,” Tiller says. “The great drama of our time is when you’re staring at your iPhone at the three dots in a text bubble, that’s become what the drama is. Early on I asked myself if we were going to do an impressionistic rendering of the internet’s reach, like Tron, and I thought no, it’s a simple human story. Waiting for an incoming message on your phone, that really is how we live our lives and experience drama now. I wanted to make Silk Road very naturalistic and grounded. With these two characters riven with internal conflicts, that’s what it’s all about above everything else. Yes, there’s a driving plot, but it’s about the characters.”

In Silk Road, while Ulbricht is creating an online emporium where his libertarian crusade turned into a transnational drug smuggling ring, Jason Clarke’s DEA agent seems like possibly the last man for the job of cracking this tech-driven case. “You’ve got this Sam Peckinpah character, out of step with the times, not keeping up, being flushed down the toilet with the changing of the guards,” Tiller says of Bowden. “Then when this case arrives, it turns out his old school knock-around skillset becomes the key to unlocking this global criminal enterprise.”

Although Ulbricht remained anonymous in the creation of Sil Road, in actuality, his run from anonymity to darknet kingpin to the notorious criminal was shockingly brief. “He was jacked into the zeitgeist instantly and irrevocably,” Tiller says. “That’s the disruptive nature of these technologies, someone goes from an anonymous stranger to a famous person in what feels like moments. The metastasis of Silk Road from ordering a bag of mushrooms to being a transnational criminal enterprise in that compressed period of time, that can only happen right now. This guy’s entire dramatic arc was compressed into 20 months, from the inception of an idea to worldwide global penetration, to completely changing the war on drugs, to being incarcerated with an incredibly draconian sentence.”

While Tiller is hardly championing what Ulbricht did with Silk Road, his film’s look at one misguided, would-be missionary’s descent into outright criminality invites us to ask some larger questions about the systems that undergird our lives, online and off. Jason Clarke’s DEA agent is far from a saint, and one could watch Silk Road and reasonably wonder if there isn’t a message about a middle way embedded in the battle between Ulbricht and Bowden.

“There’s an element where this is about generational conflict, political conflict, the things roiling America, I’m trying to explore obliquely in these characters,” Tiller says. “Millennial versus the dinosaur, the bomb the system libertarian versus the law and order ethos. The individualist versus someone holding and abusing the public trust. So many issues that were bubbling under the surface.”

Ulbricht is currently incarcerated at the United States Penitentiary in Tucson, Arizona, where he’s serving a double life sentence, plus 40-years, after having lost his appeals to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court. The issues Tiller gets at in Silk Road, both overtly and covertly, still remain.

Silk Road is available on Digital, On Demand, select theaters, and on Blu-Ray and DVD.

Featured image: Alexandra Shipp as Julia, Nick Robinson as Ross Ulbricht, and Daniel David Stewart as Max in Silk Road. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Lionsgate