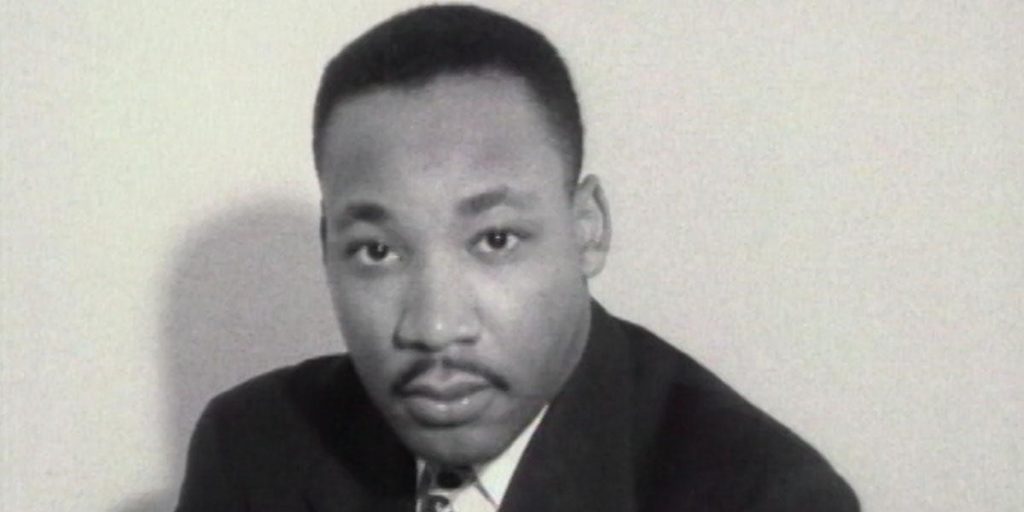

Documentarian Sam Pollard on his Must-See New Film “MLK/FBI”

A couple of days after Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his era-defining “I have a dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial, J. Edgar Hoover’s second in command at the FBI penned a memo describing him as “The most dangerous Negro in America.” As documented in Sam Pollard‘s new film MLK/FBI (On Demand and in select theaters), that 1963 memo launched the Bureau’s obsession with discrediting America’s foremost civil rights leader by tapping his phones and bugging the hotel rooms he stayed in. This “COINTELPRO” surveillance initially targeted King’s friendship with a former Communist Party member named Stanley Levison but later culminated in an anonymous letter sent to his wife, Coretta King, along with an audiotape purporting to document her husband’s sexual infidelities. Newly declassified reports inspired David J. Garrow’s book The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr.: From “Solo” to Memphis, which in turn served as foundation for the film.

Emmy-winning Oscar nominee Pollard, a frequent Spike Lee collaborator, has edited, produced, or directed some four dozen projects, including the Sammy Davis Jr. biopic I Gotta Be Me and episodes of the civil rights series “Eyes on the Prize.” He got the idea for MLK/FBI while shooting a documentary about blues musicians Skip James and Son House. “Making Two Trains Running, set in 1964, I read a copy of Garrow’s book,” Pollard recalls. “I knew about King’s infidelities but I didn’t know the extent to which the FBI monitored them. I told my producer, ‘This could be our next film.'”

To that end, Pollard enlisted off-screen narrators including civil rights veteran Andrew Young and former FBI director James Comey. Their voiceover accompanies archival footage including rarely seen home movies of King playing with his kids along with dramatizations of FBI spies in action.

Speaking from his office in New York City, Pollard digs into the Bureau’s abuse of power, contrasts King’s Lincoln Memorial peace rally with 2021’s Washington D.C. riots and considers the potential blowback when the FBI’s King-related tapes go public in 2027.

You’re well versed in the history of civil rights in America. What most surprised you during the making of this documentary?

One of the big surprises, listening to [King biographer] Dave Garrow when we visited him with our camera crew at his house in Pennsylvania, and then doing more research afterward, was the length the FBI went to undercut Dr. King. I mean, it’s one thing to wiretap him because they thought he was connected to Communism, but when they tried to use his personal life to destroy him, going so far as to send this letter in someone else’s name saying that Dr. King was a monster and should consider doing away with himself? And on top of that putting together an audiotape of [Dr. King in] a situation with another woman, and sending that to Coretta King? It’s mind-boggling. To me, the FBI went too far in its zeal to destroy Dr. King.

MLK/FBI begins shots of 250,000 people gathered in 1963 at the Lincoln Memorial listening to King give his famous speech. How would you contrast that historic day in Washington D.C. with the very different January 6th riots 58 years later?

It’s very simply this: the masses of people who congregated at Lincoln Memorial in 1963 were peaceful, standing arm in arm, listening to people like Ossie Davis, Joan Baez, and Bob Dylan. They were there to talk about inclusion in America. “We should be heard.” “We are as American as anyone else.” The group of people in Washington last week were not there for peaceful protest. They were there to destroy. And it’s not an anomaly in American history. It’s part and parcel of what Americans can be like.

Your documentary details the FBI’s abuses of power orchestrated by J. Edgar Hoover but in doing so, the film also by necessity revisits Dr. King’s imperfect private life. Did you have mixed feelings about how renewed attention to these flaws might impact Dr. King’s legacy?

That’s one of the conversations I had constantly with my producer: by making this film are we doing exactly what the FBI wanted to do back in the sixties? Are we being complicit? I had to really grapple with that question. If we had done this [focused on] what I call the “gotcha” moment, I think we would have been complicit. But what we tried to do was to leave some open-ended questions that may or may be resolved when the tapes are released in 2027.

How do you feel about the National Archives’ future release of those tapes?

Charles Knox, the former FBI Agent interviewed in our film, feels there’s no good to be had from it. But my feeling is, I would like to hear what’s on those tapes. I m not saying I want to listen to stuff that’s supposed to be tawdry. I want to hear those conversations between King and Ralph Abernathy and Dorothy Cotton and Wyatt Tee Walker and Andy Young about their strategies for Birmingham, Selma, or even Chicago when they went north. That’s what I’d be curious to hear.

Because the FBI presumably recorded so much on tape.

Whenever the FBI knew what town King would be visiting, it was all hands on deck. They had many agents observing the activities of King and his associates, which leads to the next question: if they were so focused on what King was doing, how come, in 1968 at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, there was no awareness about this man who was getting ready to assassinate Dr. King? We may never know the answer.

King is such an iconic figure I imagine it was challenging to find fresh footage?

We gave our archival producers a list of what we called the usual suspects: Birmingham, the Lincoln Memorial speech. But a good archival producer will then go the extra mile. Brian Becker found video of King talking to a newsman, looking so young and vital, he found video of King playing with his children, shots of James Earl Ray being captured at Heathrow Airport by Scotland Yard. That’s what a good archival producer can do. And the audio! I had never heard LBJ’s conversation with J Edgar Hoover. I mean, this stuff is priceless.

I assume the scenes of FBI agents were re-enactments?

We staged stuff of the FBI using their reel to reel tape recordings, going through files, using all the gadgets. We gathered those props and started building the soundstage three or four days before New York City shut down because of Covid. We’d originally planned to shoot for two days but the production designer told me we had to get everything the next day or he’d be gone. So we worked a 12 hour day, got everything in the can, and the next day they closed New York City down.

Next up, I understand you’re making a documentary about the Negro Baseball League and the famously under-appreciated pitcher Satchel Paige?

I hope so. If the money’s out there, sure that will be the next one. But I got one that’s going to premiere on HBO next month called Black Art in the Absence of Light. And then next year, I’ve had a film in the works for many years about the great jazz drummer Max Roach, which I hope will come out.

Based on the many documentaries you’ve made about African American talents, what would you describe the extra degrees of difficulty that come with being a Black artist, a Black musician, a Black activist?

You know the answer to the question, man. Look at the long list: Paul Robeson, Harry Belafonte, Billie Holiday, Sammy Davis Junior. Look at all the obstacles they had to face even with the tremendous talent they had, just because they were people of color. It’s still like that because, it’s still America, man. It’s not like an open door: “We embrace you whole-heartedly.” [Progress] takes a long time. It’s always uphill. But the thing to do is to keep on the road. Keep fighting, keep your voice out there, be as creative as possible. The challenge is to stay on the path because the struggle will always be there. Dr. King knew that.

Even after his wonderful “I have a dream” speech, the FBI called Martin Luther King. . .

“The most dangerous negro in America.” A guy who’s a non-violent activist giving a speech being “The most dangerous negro in America.” Imagine that.

Featured image: Dr. Martin Luther King in Sam Pollard’s ‘MLK/FBI’. Courtesy of IFC Films. An IFC Films Release.