Translating the Untranslatable: The Impossible Art of Subtitling “Taco Chronicles”

Subtitle translation is a fascinating, complicated, and often overlooked part of the filmmaking process. It’s a delicate dance of literal translation and cultural interpretation, all the while practicing a serious economy of words. Most subtitles are capped at only forty-four characters (less than this sentence). Plus, the eye reads much slower than the ear hears.

My own up-close experience with the art form came with Netflix’s Taco Chronicles (Las Crónicas del Taco), which I produced along with my colleagues Pablo Cruz, Arturo Sampson, Carlos Pérez Osorio, and Isabel López Polanco. While our Mexico City-based team was bilingual, I was the American and native English speaker amongst the group, so it fell to me to do the final review of each episode’s subtitles. I set aside a few hours. Only when I opened the first SRT file to discover that limón was translated to lemon instead of lime did I grasp that those little white words running discreetly across the bottom of the screen had the disproportionate power to make or break the show with our international audience. If we’d gone to air telling English speakers that the best accompaniment to a warm tortilla, filling, and salsa was a squeeze of yellow lemon — a fruit that virtually does not exist in Mexico — it would have all been for naught. One citrus family slip-up could have set aflame the credibility we were trying to build and insulted a nation.

Why? Because for so many people, food is identity. When author Alison Roman denigrates rice, a dietary staple for half the world’s population, to a mere ‘filler’ not worthy of inclusion in her book or Jamie Oliver mucks with Jamaican recipes, they are tampering not just with ancient grains and jerk chicken but with people’s memories, sense of where they come from and who they are. Understandably these media stars, their publishers, and networks are called out. Food, like language, can be a tool used to unite but has also long been used to divide, colonize, and erase.

The few hours I had set aside to review Taco Chronicles’ subtitles turned into several days of poring over the words, chewing over various translations in my head and with my colleague Isabel, and reaching out to friends and experts. Some decisions came easily, such as that we’d leave chile in its original form, not change it to chili, which isn’t incorrect per se but can connote the meat-and-or-bean stew or the dried spice mix with garlic and cumin. But there were areas of greater nuance that felt not only difficult to parse but also high stakes.

The format of our series very much relies upon distinct regional cultures. Each episode centers on a style of taco and the state or city from which it comes or was popularized. So both the dialogue and scripted voiceover are peppered with hyper-local references, slang, expletives, portmanteaus, and double entendre. Interpreters agree these elements of language that are closely tied to geography, climate, and culture are the hardest to adapt. But they are also what distinguishes one region from the next, the same way a recipe for mole in Oaxaca will be different from one made in Puebla. During filming, specificity was our guiding principle. We wanted to honor the richness of Mexican cuisine and all the ancestral knowledge behind it by capturing techniques and ingredients in great detail. It felt important to carry over that commitment to specificity to the subtitling process. We knew that the US was our biggest audience outside of Latin America, and many of those viewers were of Mexican origin.

When Taco Chronicles premiered last summer, complete with subtitles we felt okay but not great about, I infinity-scrolled my way through the public’s reactions on Twitter. I toggled back and forth between the #lascronicasdeltaco and #tacochronicles hashtags to see how it was received on both sides of the border, fascinated by the two ginormous discussion rooms and the immediate access to feedback social media provides. Each episode was picked apart, its most memorable moments screenshotted, presenting subtitled or close-captioned text on top of a visual. In the #tacochronicles search window, it became clear that the subtitles were as much a part of the viewing experience as the photography, animations, and music.

I was especially drawn to the reactions of viewers who were bilingual and bicultural: Mexicans living abroad, Mexican-Americans, people who lived around in the borderlands. Having not just familiarity but intimacy with both languages and both cultures made their approval what I most sought after. If watching with the English subtitles on, would they have agreed that chingón should have been been ‘f**king awesome’ instead of ‘freaking amazing’? What about the word guisado? We translated it to ‘stew’ but not all tacos de guisado are filled with stews. The chile relleno, a fan favorite, is a battered and fried chile stuffed with cheese wrapped in a tortilla. Nothing soupy about it. Would they cut us some slack and recognize the impossibility of a perfect translation? I knew our word choice was under the lens.

Confirming my hunch, in November Netflix tweeted from their “Spanglish” account @ConTodo that “bilingual culture is turning on the English subtitles when you’re watching TV just to judge the translations.” Widespread access to streaming services like Netflix has created a buffet of international movies and television shows subtitled in umpteen languages. This growing array of content coupled with the rise of bilingualism in the United States has thrust subtitles into the spotlight — despite the fact that the spotlight is precisely what they were designed to avoid. The prefix sub- in Latin means below. They are meant not to distract and therefore placed out of the way.

When we geared up for a second season, at the top of my priority list from the first season’s post-mortem was finding a translator who would not just succeed in the technical aspect of the job, but also embrace the creativity and help us win with US Hispanics. We found a pool of qualified interpreters and served up the hardest edit test we could muster: the Suadero episode. Alejandra Garza’s translation was by far the favorite, and she soon came on board.

In a recent phone interview, I asked her about the biggest challenge she faced on our project. “The slang!” she cried. It’s true, the Suadero episode is strewn with albur, a distinctly Mexican approach to double entendre, usually sexual in nature. “I grew up in Mexico City — or Cuernavaca which is near Mexico City — so I would understand everything they were saying, but how, I wondered, am I ever going to be able to put that in English and keep the same register, idea, and the same…spark? It was hard.” We rehashed the different dilemmas that we faced. For example, how to translate longaniza, a sausage that’s similar to chorizo? We left chorizo itself in Spanish, but the character limit did not allow for the long-winded explanation that longaniza is encased in longer segments than chorizo and also benefits from an added kiss of achiote. We translated it simply to ‘sausage.’ Another example: Queso asadero is a cheese made in states like Chihuahua that melts perfectly in burritos and quesadillas. Alejandra had never tasted it before, so she called a friend from the North who could describe it to her in detail. Convinced there was no English equivalent, she left the word in Spanish. As we faced one word after the next, we often decided to leave the untranslatable words, of which there are many, in Spanish despite her general belief that as few words possible should be left in the source language. But I did start to wonder how much responsibility we were allowed to bestow upon our viewers. Where was the line between over translating and under translating?

I reread Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Task of a Translator,” which I remembered from college, for no other reason than by the looks of its title I thought it might help me get clarity around the responsibilities that came with Alejandra’s job (though it was written about literary translation, not subtitling for global VOD platforms). As I slogged through the dense text, translated from German to English and written a hundred years ago, I wished for a translator to simply make understanding his academic speech easier and faster.

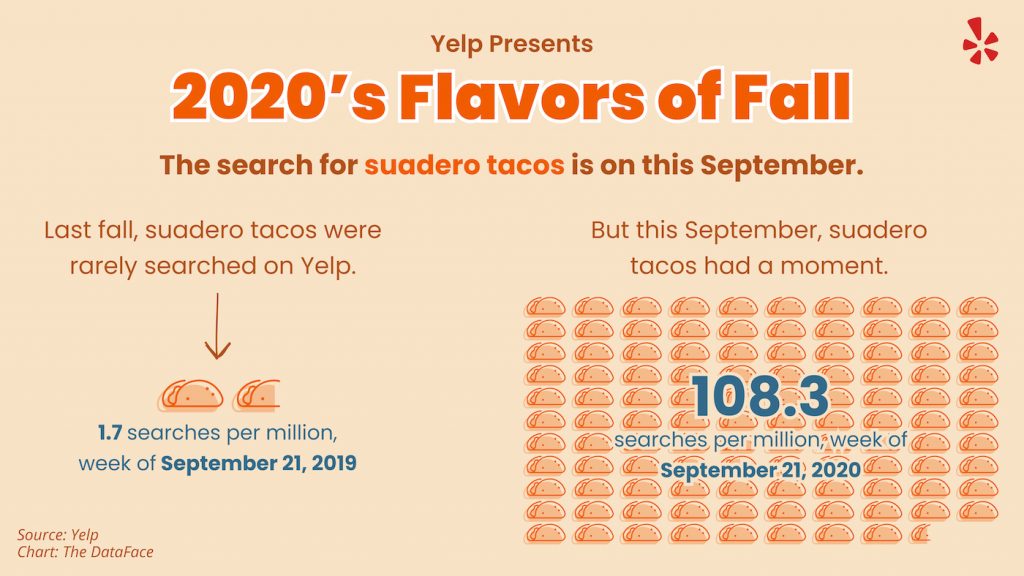

“Our job, our ethic as a translator is to communicate. You need to feel that the reader, the listener, feels connected to the speaker, the movie, the article, or the book. They need to read it or hear it as if it were spoken in their own language,” Alejandra told me. “But there are words and ideas that are impossible to translate. There are concepts in Spanish that don’t exist in English.” We talked about sobremesa, the term used to describe the Mexican ritual of lingering at the table for gossip and coffee (or a cordial) after a meal with family or friends. There’s no cultural equivalent in the US — we scratched our heads looking for a roundabout explanation. And of course, there’s suadero itself — a tough cut from the underside of the cow rendered delectable by slow cooking. This specialty from Mexico City needed to be left in Spanish precisely to highlight its origins. Could we expect those unfamiliar with the dish to look for more information after watching our show? Turns out we could. Search for “suadero tacos” was up approximately 1000% year over year the week our show premiered.

As a Romantic, Walter Benjamin would have seen these ‘untranslatable’ words not as limitations but rather as opportunities. He believed that translation should not seek to merely convey information or replicate the original but rather be a continuation of the creative process: “Fragments of a vessel which are to be glued together must match one another in the smallest details, although they need not be like one another. In the same way, a translation, instead of resembling the meaning of the original, must lovingly and in detail incorporate the original’s mode of signification.” (I interpret ‘mode of signification’ to mean intent.) To Alejandra’s work, which ‘lovingly and in detail’ weaves together English that is both clear and creative with Spanish that honors the uniqueness of a land, its ingredients, and people, I believe Benjamin would say job well done.

But Benjamin is a long-gone philosopher. Real validation for the technical and creative work of professional subtitlers for television and film (heck, video games too!) would come if the major awards ceremonies recognized their contributions with a category. When we stop thinking of subtitles as a “one-inch tall barrier” and start thinking of them as an instrument for a richer cinematic and cultural experience, maybe we’ll have more appreciation for the growing field of people who make that possible. Change.org petition coming soon.

Taco Chronicles season 2 is now streaming on Netflix.

For more stories on Netflix, check these out:

Showrunner Chris Van Dusen on Creating a Modern Regency Romance in “Bridgerton”

David Oyelowo & Demián Bichir on George Clooney’s Timely Sci-Fi Film “Midnight Sky”

Production Designer Mark Ricker on Creating the Sumptuous “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom”

Branford Marsalis Gets the Blues For “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom”