Game of Thrones Director Jeremy Podeswa on Last Season’s Toughest Episode

Jeremy Podeswa has directed some of the most ambitious television episodes of the last ten years. Rome, Six Feet Under, The Walking Dead, True Detective, Homeland, True Blood, American Horror Story, and Boardwalk Empire are on his resume. He’s been nominated for three Emmys—one for the HBO miniseries The Pacific, one for a 2011 episode of Boardwalk Empire, and now one for his work on the episode of “Unbent, Unbowed, Unbroken” for a little show called Game of Thrones.

“Unbent, Unbowed, Unbroken” was season five's most controversial episode. (Spoiler(s) alert.) For all the chess piece movements of this dark episode, none brought as much reaction, and horror, as Ramsay Bolton's rape of Sansa Stark after their marriage in Winterfell. In sixty minutes worth of reveals (Jorah Mormont discovers his father is dead), betrayals (Littlefinger promises Cersei he'll bring her Sansa’s head on a spike), not one but two marriages of convenience (along with Sansa's marriage to Ramsay, Dany arranges a political marriage in Mereen), rescue attempts (Jamie and Bron trying, and failing, to spirit Jamie's daughter Myrcella out of Dorne), and weirdness (Arya’s continued apprenticeship under Jaqen H’ghar at the House of Black and White), nothing matched the intensity of Sansa's rape. The unfolding horror of her life—a character once loathed and now beloved by many GOT fans—reached what you'd like to believe was its' absolute nadir in this episode. Many fans were incensed. All of them were floored by an episode so filled with emotion.

We talked to Podeswa about that episode, as well as “Kill the Boy,” another GOT barnburner he directed last year, and what it’s like to work on one of TV's most ambitious, beloved, and scrutinized shows.

From a logistical standpoint, what’s it like directing an episode of Game of Thrones?

The way the show is structured is that every director does two episodes, which is two hours, so essentially it’s like directing a movie. This show is so ambitious. We were shooting in multiple countries— Spain, Croatia, and Ireland. You’ve got this huge ensemble cast and this epic cinematic quality. So when you’re prepping and shooting, it’s like making a movie. Not a simple movie, either.

How long does it take to shoot two episodes?

It’s a five month commitment for doing two episodes. It requires that much time because the scheduling alone is so complicated. There’s at least two, sometimes three crews shooting in multiple countries, so at any given time there’s three or four episodes shooting at once. To juggle this jigsaw puzzle is so complicated. Logistically, it’s amazing, everyone deserves a ton of credit.

Let’s talk about what you felt reading the script for "Unbent, Unbowed, Unbroken."

When I read the script, I thought it was very strong dramatically, and it offered a lot of opportunity for epic sweep and scope. This episode in particular gives you many challenges, but also many opportunities. There were more David Lean like cinematic epic scenes, but also action, character work, drama, things for actors to play. In a single episode you get many different worlds, many different tones, and it’s very complicated viewing experience, but a rich one. You get lovely character work and fine work with actors, at the same time you get to use a very rich pallet for the show generally.

There was a lot of outrage over Ramsay’s rape of in “Unbent, Unbowed, Unbroken.” How did you feel about that?

To me it’s an indication of peoples investment in these stories and these characters. Look at the very first episode of the series— Jamie Lannister pushes Bran Stark out of the window, paralyzing him, and five seasons later, people love Jamie Lannister. I think the way people perceive behavior is relative to the way they relate to the show and the arc of the series, and the longer the series goes on, the more people invest in these characters, and the more they care when terrible things happen to them. Characters being killed, brutalized—people understandably start to take it very personally because they’ve invested so much in them.

Part of every fan’s bargain with GOT is that their favorite character might get killed, or at least have something horrible happen to them, at any point.

Since Ned Stark got killed, I think that was the tip off that even with someone you invested in hugely, that anything could happen, the gloves were off. I think in a way there’s almost an expectation of being shocked that the audience has at this point, but they don’t really know how it’s going to happen. Part of the viewing experience is the highs and lows, it’s a journey. Maybe the journey is harder to take now that they’re more invested, and the harder things are really getting harder. I feel there’s a kind of audience investment this past season that’s reached a point where people are so invested that they’re taking things very, very personally.

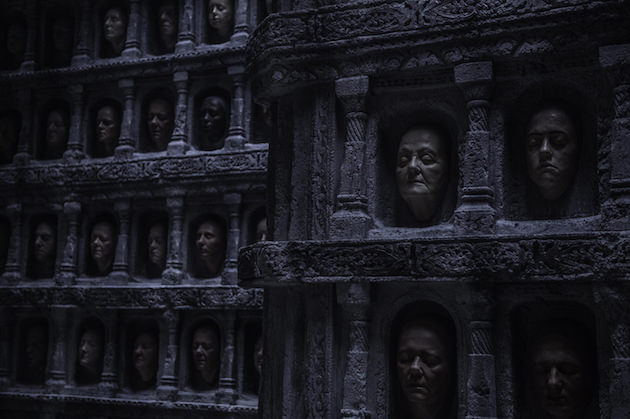

Let's talk about some of your challenges in this episode, like creating the House of Black and White, and, specifically, the Hall of Faces.

Establishing new sets is always great. The House of Black and White, and, inside of it, the Hall of Faces, were totally new. I was involved in its conceptualization and how to deal with it and what it was going to look like—it was wide open when I got involved. Everyone thinks we have unlimited resources, but we don’t. In the earliest discussions of what The Hall of Faces was going to look like, we agreed it had to be incredibly vast and spectacular, but then we feared we couldn’t do it properly with the resources we had, so there was talk to reduce the scope. When I saw that there’d been a huge come down on our way of approaching it, I was disappointed because I thought it really needed that spectacular vision—when Arya steps into this hall, it should be like stepping into another world. I spent a lot of time talking to our team about how to achieve our original vision, but to make it economically viable. So what we ended up doing is building pieces of the set, and then used effects for rest. We minimized the number of shots and angles because we realized if we could be very specific of how it was shot, we could be grand in vision.

Along with choosing your angles and shots carefully, how did you go about constructing the most important part—the faces?

The issue was—‘what are these faces, how do they look, where does the light come in?’ We did many, many tests, and we knew we didn’t want the faces to look like Jack-O-Lanterns, with lights behind them—we wanted them to look real, which required a lot of testing and exploring with our prosthetics people. We finally got the look and I was very proud of it. It involved so much care and thought by a lot of people.

What are the faces made with?

Hundreds of those faces are molded, handmade, which was a big expense, and we took a lot of care with them. Some of the faces are people from the show—Dan [Weiss] and David [Benioff] the producers, they’re in there, a number of people from the team. The featured face, the woman’s face that she touches, is actually the mother of one of the prosthetics people. Many of those faces were modeled and made from scratch, and beautifully rendered.

There are a lot of powerful one-on-one scenes between characters in this episode.

A lot of times the really satisfying scenes are the really simple ones. I love the scene with Cersei and Olenna, just two really strong actresses; those scenes are a pleasure to do. As are scenes with Jorah and Tyrion, they have such a great chemistry.

I also loved shooting the scenes with Sansa and Ramsay in Winterfell. It was a horrific version of Sansa’s homecoming in a way with the difference in what Winterfell used to be and what it was when she returned. And the scenes in Dorne, we were actually shooting those in the Alkácar in Seville, Spain, these water gardens that are really beautiful. They never close it down, never for shooting a film, but they allowed us to shoot there for a substantial number of days. And the Sand Snakes fighting with Jamie and Bron, that was really fun to do.

In your other episode last season, “Kill the Boy,” you had another first—the ancient city of Valyria and the first appearance of the Stone Men. What challenges did you face there?

With “Kill the Boy,” the ruins of Valyria and the Stone Men sequence—there was really no road map of how to shoot that or conceive of it. No one knew what these Stone Men really were or what they looked like, how they fought, how they moved. And what does Valyria actually look like? It’s been eluded to, but nobody’s ever seen it before. There was an enormous involvement with me and the production design team and producers—was it going to be shot in studio, on location?

Then we finally nailed it down. Of all the prep that I did, half of the prep time was devoted to that sequence. Ultimately we shot in a number of water locations, one was on an open water lake that lead into a tributary that led into an aqueduct where the Stone Men attack Jorah and Tyrion. A lot of the effects were the ruins of Valyria that were put onto a real landscape.

There’s not much of the Stone Men in George R. R. Martin’s books—how did you decide how they looked and fought?

First, the aqueduct where the Stone Men stage their attack was a complete recreation. We built a platform for them to jump from onto Jorah and Tyrion’s boat—all the ruins are VFX, but we did have an actual set for the fight. It sounds very simple once it’s all figured out, but until you figure it out and find a location, you could really go so many different ways.

As for their actual look, those were big questions—many conversations with Dan [Weiss] and David [Benioff] were about how they felt about these Stone Men. In the books there’s very little to go on—they’re described in a completely different context in the books, so it didn’t really help me a lot in conceptualizing what these guys were. There needed to be a kind of reality base to them, and they need to have once been human, and now they’re a version of a diseased human. The theory was they’d gone mad from their disease. But then again, we didn’t want them to be like The Walking Dead, or identifiable as anything that's been done. There was discussions with choreographers and movement people to give them a certain character.

Do you have a sense of where things are headed?

You really don’t know what’s going to happen. You have to be true to the narrative and the ethos of the show. The creators and writers continue to be perversely, uniquely individual. They follow their own integrity of what they think should happen to these characters. It’s a show about people dealing with and trying to get power, and the subversion of expectations is really a big part of that. I think they’re quite brilliantly straddling this line of trying to stay fresh, keep the audience on their toes, and stay true to the world they’ve established. If the story became predictable, there’d be no interest in watching the show.

Any hints about next season?

I’m in the cutting room in Belfast right now, working on the editing. I’m more than halfway through the first two episodes of next season. I think season six is going to be amazing—it’s very good story telling, every character has something interesting going on, and there are many surprises, great and terrible things are coming, with more fantastic locations and beautiful set pieces.

Featured image: Sansa Stark (Sophie Turner) and Reek (Alfie Allen) await Sansa's marriage to Ramsay Bolton. Photo by Helen Sloane. Courtesy HBO.