Composer Vivek Maddala Underscores Discrimination in Asian Americans Documentary for PBS

The versatile composer Vivek Maddala recently shifted gears from his zany Emmy-winning music for Cartoon Network series The Tom and Jerry Show to score PBS’ somber documentary Asian Americans (debuting May 11). A musical prodigy, Maddala enrolled in Boston’s prestigious Berklee College of Music at age 15 with dreams of becoming a jazz drummer but switched to electrical engineering at Georgia Tech before earning a graduate degree in applied physics. “I’d been the hotshot drummer in my home town but when I got to Berklee in the late eighties, there were a million other guys just like me,” Maddala laughs. “With the proliferation of drum machines, it didn’t make a lot of sense for me to pursue drumming. And also, I realized my strengths were in composing and producing.”

While finding his groove as a film and TV composer for projects including Peabody Award-winning documentary American Revolutionary, Maddala built his own recording studio in the backyard of his West Los Angeles home. That’s where he produced four and a half hours of music for the five-episode Asian Americans series. “This was pre-quarantine, so I was able to bring string, woodwind, and brass players over here in small sections to record the score,” Maddala says. “I played all the percussion, piano, bass, and drums myself.”

Speaking from home with his grand piano within plinking distance, Vivek delves into the inspirations behind his score for PBS’ examination of American racism directed at immigrants from China, Japan, India, the Philippines, and Southeast Asia.

Your Asian American music draws on a lot of different styles. What was the overall approach for utilizing these sounds?

The thing about scoring documentaries is that you have to calibrate very precisely what you’re saying with the music, and what you’re not saying. We live in this propagandized world where everything’s being spun in all kinds of crazy directions, so modern audiences are very sensitive to being manipulated by music. I wanted the music to half-pose a question and invite the audience to complete the circle themselves.

Episode One’s Angel Island sequence, for example, documents how badly Chinese people were treated when they arrived in San Francisco?

Asian immigrants coming over in the early 1900s landed in Angels Island, this brutal environment where parents were separated from their children. It’s not a huge leap to connect the dots to what ‘s happening right now, but how much do we want to punctuate that with the music? It was a particularly tricky cue because director Leo Chiang’s aesthetics are very austere. We ended up doing the main melody as a single violin, which can be schmaltzy depending on how it’s executed. But here, we wanted to gently nudge the audience in a particular direction without hitting them over the head.

How did you go about creating the musical theme that recurs throughout the series?

Episode One talks about The Chinese Exclusion Act, where people of Chinese origin were not allowed to become American citizens. If you’re from China, you could try to change the system. Or, you could navigate the system to improve your own personal situation and that of your family. The director called this “resigned acceptance,” where people just make the best of a really difficult situation. As a musical analog for this idea, I based my theme on a perfect fifth, which is a very comfortable interval. But then it alternates between an augmented fifth and a diminished fifth, which creates this slightly unsettling dissonance when the contrapuntal lines rub up against each other. [Maddala demonstrates on the piano]. At one point it’s played on bass clarinet and harp. At another point, flute and piano. In creating this musical motif of resigned acceptance, we’re inviting the audience, on a subliminal level, to understand the connection between these [oppressive] situations without explicitly telling them what to think.

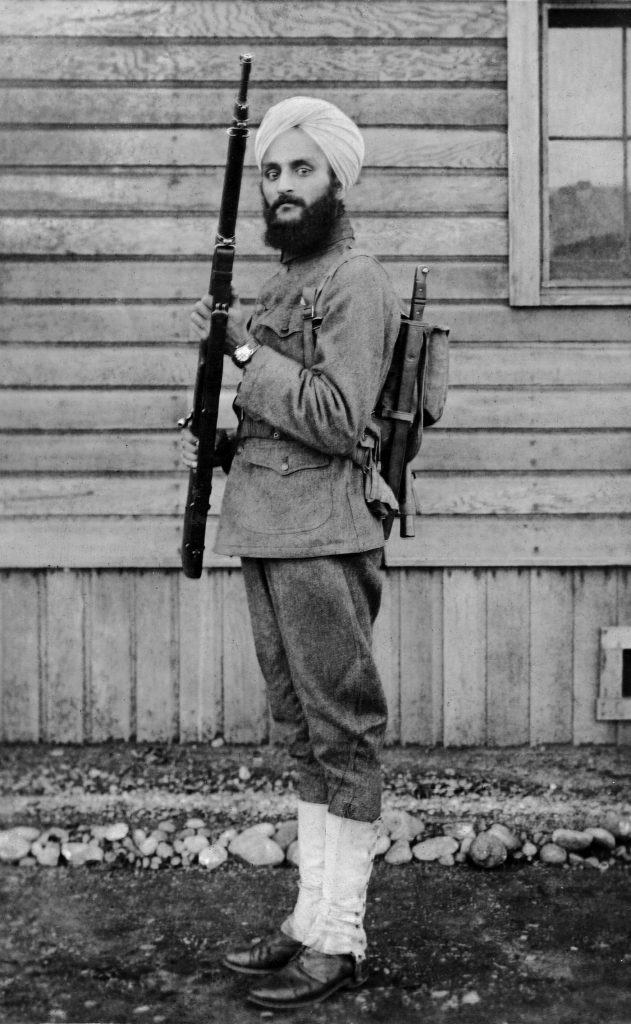

Your music takes a different direction in the story about Sikh men who moved from India to America, where they played up their ethnicity to work as street peddlers.

Generally, we didn’t want the score to sound “Korean” or “Filipino,” for example, in terms of being geographically specific to the cultures. But this particular section of the documentary talked about how men from south Asia came to America and became part of this peddler network that played into this orientalist concept of the “exotic.” So here, the music is overtly south Asian sounding in a way that’s almost a parody of what people at that time period might have associated with India.

How’d you achieve that sound?

I played the tambura, an Indian drone instrument, and this kind of clay pot called the ghatam, as well as the kanjira and the bowed string instrument called the sarangi.

You must have a nice collection of instruments in your backyard studio?

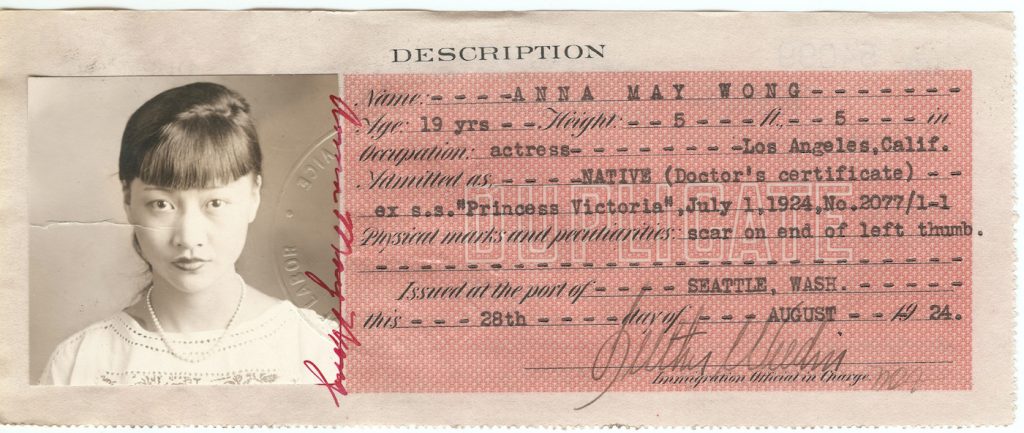

I do. I’ve got a lot of stuff from around the world, and I also have my beloved Gretsch drum kit, which you hear in the New Orleans stuff and the big band transition going into Anna May Wong’s story. I mostly use a Black Beauty snare, designed in 1922, which was featured on all those great Motown records.

Episode 4, which deals with the Asian American experience Vietnam War era, called for a different kind of feel?

I’m a huge fan of the Tower of Power brass section – – one trumpet, one trombone and tenor, alto and bari saxophones. There’s something grittier, slinkier, and kind of dirty about the sound, so I went for that sax-heavy sound for the things that happen in the sixties and seventies. For some reason, the saxophones sit better in the back of the dialogue.

As this documentary reminds us, America is very much a nation of immigrants. What about your family?

My parents are from India. There were a lot of experiences described throughout this documentary that were familiar to me in terms of my understanding of history and also in terms of my personal experiences. But I like to think that people are empathetic enough to understand human suffering and struggle without experiencing it firsthand.

Featured image: Vivek Maddala at the Piano. Courtesy Vivek Maddala.