The Irishman Cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto on Crafting Scorsese’s Masterpiece

Beloved auteur Martin Scorsese’s new film The Irishman has brought Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci together onscreen for the first time in 24 years and added Al Pacino, whom he’d never worked with before, building a cast that sounds truly compelling to lovers of great acting and great film. Based on “I Heard You Paint Houses,” the narrative nonfiction book by homicide detective Charles Brandt, the story centers on Frank Sheeran (De Niro) who, wheelchair-bound in a rest home, reflects back on his life as a hitman for organized crime, and on his lifelong relationships with Sicilian-American mobster Russell Bufalino (Pesci) and Teamsters head Jimmy Hoffa (Pacino).

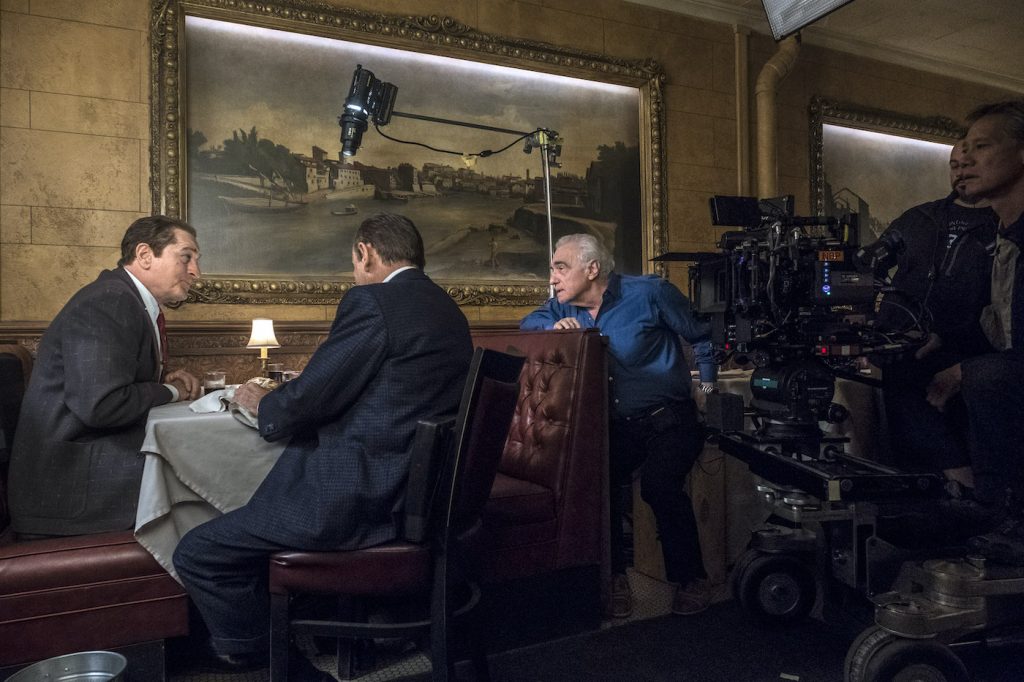

Scorsese enlisted Rodrigo Prieto as director of photography to help bring his vision to life onscreen. Prieto has Oscar nominations for his work on both Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, and Scorsese’s 2016 film Silence, but this new film offered new challenges.

Joe Pesci (Russell Bufalino) , Robert De Niro (Frank Sheeran). Courtesy Netflix.

The three lead characters in The Irishman are represented in many life stages, necessitating the invention of new age-manipulating technologies that could show age progression of 30 years or more. Prieto worked with Pablo Helman, visual effects supervisor at ILM and his special effects department, and used a new three-camera system, two of which were used to create recordings of the actors for later alteration. This meant where there was a two-shot, there’d be six cameras, and so on. It was all about triangulation, and getting both the main shot and those the special effects wizards would alter later, all lit in the same way.

“The one worry I had was to make sure the lighting would be reproduced accurately by the visual effects,” Prieto says. “We took a little bit of time after each setup for the team to come in with their tools, and they took photographs of all the surroundings including the lighting with different exposure levels, and had a color chart. Every setup, we had to take a few extra minutes, but they did use all this information. I knew they needed the time to do it right because all this care I took into lighting the scenes wouldn’t matter if they didn’t have their information correct. It was pretty amazing that they were able to not only track the performances, but the lighting. When I was color timing the movie, I could see they matched everything seamlessly. Then I could do my color timing as I would do in any other movie. I didn’t have to compensate or make adjustments because there was CGI.”

Collaboration is inherent to cinematography, as Prieto explains, but he says on Scorsese’s sets, all creativity and new ideas offered by those present are considered, and often embraced.

“In terms of collaboration for the cinematographer, after all, everything that everybody is doing including the screenwriter, costume designer, production designer, director, and actors, everything is aimed at that little lens that is the synthesis of all that, which gets captured on the negative or the sensor,” Prieto says. “The cinematographer is the one in charge of that, so it’s pretty crucial that everyone is in sync with the cinematographer, to make sure the job everyone is doing is registering in a good way.”

Despite his credentials as arguably the greatest living director, Prieto says that Scorsese is an open, collaborative presence on set.

“In particular, with Scorsese, he is obviously a master, that’s undisputed, but he is also a really good listener. I think that’s why he’s so good with actors, because he really appreciates their input, and makes sure that if an actor wants to approach something in a particular way, that we all accommodate that. For example, on Silence, Andrew Garfield needed to witness things to get to an emotion, so every close-up of Andrew’s, we always set up the whole village, and the samurai, and all that off-camera, and so he would see it for the first time. To Scorsese, that’s what Andrew needed, so that’s what we all had to do. He’s very respectful of people’s processes. He has a particular design in mind, but he’s always allowing for improvisation, and things that will come up on set, and he’ll do it. In terms of cinematography, he really gives me a big leeway with lighting, and proposing lenses, which is really thrilling. I show him references, and he does really focus on that.”

Though Scorsese is, by his own admission, obsessed with cinema, he has rarely brought up films as references when working with Prieto. He did recommend he watch Carlo Lizzani’s 1974 film Crazy Joe, about the life and death of Joe Gallo. Gallo’s murder, on April 7th, 1972 at an eatery in Manhattan, is also portrayed in The Irishman, but in a far more realistic way, and based on copious research.

“For Umberto’s Clam House, where Gallo was murdered, we reproduced it exactly,” Prieto says. “We based it on photographs and films. In fact, there’s a point where Frank Sheeran is watching a newsreel, showing police outside the restaurant, and it’s real. What we recreated looks identical. But it’s tricky because there’s no place left like it in Manhattan, so we picked a street in the Lower East Side, which was similar in architecture, and created 2/3rds of the facade, one part of which had to be blue screen. The entrance itself was an entrance of a shop, not a restaurant, so that had to be a blue screen. I lit the whole street, it was at night, and I lit the facade, and the streets on the side. The shot has the camera see the place, and goes in through the doorway, and then into the interior, which is actually on a soundstage. We did this transition onto the soundstage, then we continued a shot on a crane, then on a steady cam. The whole thing is seamless. That’s the kind of trickery that I really enjoy.”

One of Prieto’s favorite aspects of his job is not only taking part in recreating a space, but enhancing it, or pushing the realism, to amplify the emotion of the scene through lighting.

“Through cinematography, visual effects, and imagination, we are able to really put ourselves back in Little Italy and at that restaurant,” he says. “I did add some flourishes with lighting. For example, for the interior, in the few photos from the time, we saw the ceiling had these little squares, which I assumed had light bulbs in them, with maybe a diffuser. We took that design, but instead, I put some really potent theatrical Lekos that went through these little squares and created these really hot points of light, and with the smoke, because people are smoking, you see these really dramatic shafts of light. It wasn’t that way originally, but that’s also what I enjoy doing, is taking something that’s realistic and pushing it. It’s a very dramatic moment, and I didn’t want a bland, flatly lit place, but it is based on research, and what it more or less might have looked like.”

The Irishman premiered last Friday in select theaters and opens wider on November 8, 2019, and then will be available on Netflix on November 27.

For more on The Irishman, check out our interview with The Irishman producer Emma Tillinger Koskoff.

Featured image: Dipping bread in wine, known as Intinction, speaks to the shared Catholic traditions of Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci) and Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro). © 2019 Netlfix US, LLC. All rights reserved.