Chernobyl’s Emmy-Nominated Director on Capturing Catastrophe

Within the first few minutes of Chernobyl, director Johan Renck plunges the viewer into a riveting recreation of the infamous nuclear power plant meltdown and its aftermath. Since completing its run this summer, the HBO mini-series has earned 16 Emmy nominations for dramatizing the horrendous impact on victims of the accident while tracking the efforts of scientist Valery Legasov (Jared Harris) as he takes on the Soviet establishment to uncover the truth about why the reactor blew up.

Before taking on Chernobyl, created by Craig Mazin, Renck had already proven himself a deft director of dark material. Raised in Sweden, the self-taught filmmaker started out as a recording artist, then shifted focus to direct music videos (Lana Del Ray’s “Blue Velvet”), TV commercials (Versace) and episodic cable dramas including Breaking Bad. In 2015, he directed the instantly iconic music videos for David Bowie swan songs Blackstar and Lazarus. “I’ve always been fascinated with death,” Renck says. “It’s such a deep well to tap into, and I find that tragedy has beauty in it. Or to say it the opposite way, the greatest beauty always has some element of tragedy.”

Emmy-nominated Renck spent two years on Chernobyl, directing the entire five-part series in Lithuania, Latvia, Ukraine, and Russia. Speaking from New York City, where he lives with his wife and four kids, the filmmaker talks about “Method directing” in a wetsuit, his obsession with authenticity and the autistic relative who helped inspire Chernobyl‘s central performance.

You were living in Sweden just across the Baltic Sea from the Soviet Union when Chernobyl blew up. How did you and your country react to that catastrophe?

On the day we heard news about Chernobyl, I remember my friend’s parents took her out of school and they moved to New Zealand. We were not allowed to eat any berries or mushrooms from northern Sweden. We’d had a referendum a few years earlier in Sweden about nuclear power and I’d been against it, so when we heard about Chernobyl, it was kind of like “See, I told you.”

Flashing forward 30 years, what grabbed you about Craig Mazin’s script?

I read the first episode and it suited me on a lot of levels, but my instinct was to turn it down because I’d just come back from a long venture in Eastern Europe [making The Last Panthers mini-series] and it was exhausting. I didn’t want to travel. But then they sent me the second episode and I really liked the subject matter. I’m always drawn to darker tragedies with a lot of layers of humanity.

Given the scale and scope of Chernobyl, what was the biggest challenge for you in bringing the story from page to screen?

To be honest, the biggest challenge for me was to do this project while trying to keep my family happy. Chernobyl took two years to make, and when I do a project, I’m completely absorbed. It’s almost like being a Method actor, except you’re the director. You sink so deep into it that you have very little of yourself or your energy to give to the rest of your life, whether it’s your relationship or your kids. I’m on my third marriage. I lost two of them because my eagerness to work had a price. This time, my family moved with me to Lithuania for eight months. We like to stick together.

Some of the wide shots in Chernobyl feel almost like oil paintings, including your vistas of the nuclear reactor glowing at night. How did you approach the visual storytelling?

I’m interested in what an image does psychologically. Filmmaking is not about making people think. It’s about making people feel. I set up the shots to make sure they draw you in, so it feels like you’re rubbing shoulders with reality. You’re in the conference room at the Kremlin, or you’re in that courtroom. Paired with that, you need a tremendous amount of authenticity.

That authenticity comes through on so many levels including these massive Soviet buildings and the power plant itself. How did you find those structures?

We spent eight months in the former Soviet states of Lithuania, Ukraine, Latvia and a little bit in Russia. We filmed Chernobyl’s sister power plant, Ignalina, in Lithuania. We went where ever we could find this type of architecture called brutalism, which emerged in this post-Stalin era. These massive, concrete buildings are not just occupying space; they’re also expressing the power of the totalitarian state, which definitely worked for our story.

What was your approach to re-creating the period?

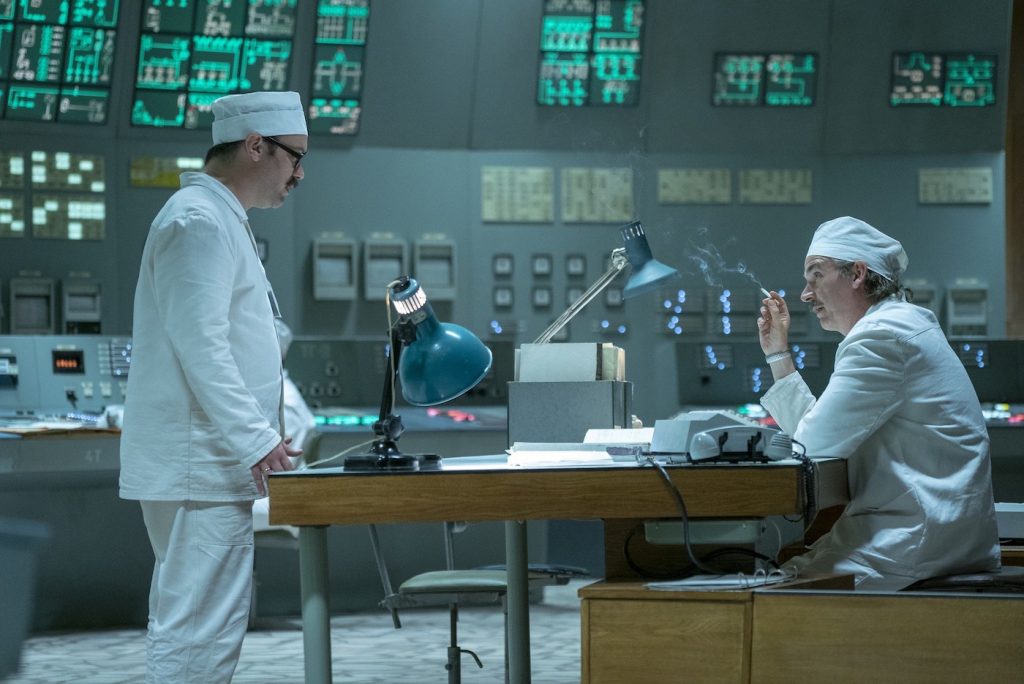

One of my main goals with Chernobyl—and this is what I told all the department heads—is that I wanted anyone who was actually there when this happened to see this series and say: “Yep, that’s exactly the way it looked, the way it felt, the way it smelled.” I wanted it to be 100 percent authentic. We put a lot of work into finding every little gadget, every little button from the right time period.

photo: Liam Daniel/HBO

And these details extend even to the supporting characters?

It’s an easy trap to think that people in Russia were worn down, miserable people wearing grey suits, because that wasn’t true. They smuggled in films and music from the west, they made their own clothes, they tried to be as cool as possible. I explained to Alex Ferns, who plays the lead miner, that he was going to have a mullet for his haircut because “You’re the chief miner but you also happened to see a Hollywood movie from the early eighties where the main character had a mullet and you wanted to look like him because you thought it was cool.” That kind of stuff is tremendously important when you’re depicting a culture.

Jared Harris gives a moving performance in Chernobyl as real-life scientist Valery Legasov. What’s he like to work with?

Jared has a lot of theater in him, which is such an important tradition in British acting, but he completely dispensed with all that to becomes this very idiosyncratic character. There’s a naiveté to Legasov because he is, I think, on some level on the autistic spectrum. Many times Jared reminded me of my father’s brother, a brilliant economist, who was on the spectrum as well. As I assessed and fine-tune Jared’s performances, I realized at some point that I wanted him to be like my sadly passed away uncle. You can’t just invent an idiosyncratic personality. I was tremendously impressed with Jared. He’s a smart guy, but also an instinctive animal when it comes to acting.

Photo: Liam Daniel/HBO

The themes of death and decay figure into Chernobyl and also played an important role in the music videos you made with David Bowie in the months before his death. What did you take away from that collaboration?

David Bowie was brilliant, tremendously clever, funny, charming, naked, truthful. I didn’t really know him at the beginning, but over the eight months of doing those videos, our relationship gained a certain intimacy because he had to tell me that he was ill and was going to die. I walked away from that experience believing you should never mask your own voice. Don’t shy away from your ideas however personal they might be because when they come out on the other end, people feel like they’re watching something different and specific.

In one of Chernobyl‘s most suspenseful sequences, three volunteers wade into the dark Chernobyl power plant after its’ been flooded with radioactive water so they can open up valves and prevent a catastrophic steam explosion. How did you pull that off?

We built a massive set with a big tank that enabled us to be there with all the camera equipment and lights. It was tricky to wade around in the water talking to the actors and the Steadicam operators, then run back to the monitors and see if it felt right. And it was hot as f**k also so I was half-naked wearing those rubbery things up to my waist. As I said earlier, there’s a method aspect of being a director where you have to become part of what’s happening. I remember those days as being bleak and austere, but in the end, the scene works. It is horrifying. But it’s not as deadly as you might remember because two of those divers are still alive today.

Featured image: Johan Renck on the set of ‘Chernobyl. Photo credit Liam Daniel HBO