Lethal Force: Sheriff Confronts SWAT Team he Founded in Peace Officer

“Since the late 1970s, there has been a 15,000% increase in SWAT team raids in the United States.” This alarming fact is revealed in Peace Officer, an extremely timely, unsettling documentary that swept the Audience and Jury Awards for best feature documentary at this year’s SXSW Film Festival. Directed by Scott Christopherson and Brad Barber, Peace Officer focuses on the increasingly militarized state of American police, told through the story of Dub Lawrence, a former sheriff (and brilliant investigator, as a young officer he helped break the serial killer Ted Bundy’s case) who established his rural state’s first SWAT team only to see that same unit kill his son-in-law, Brian Wood, in a controversial standoff 30 years later. Dub was at the scene when it happened. Wood had been accused of physically abusing his wife, and was in the cab of his pickup threatening to kill himself when the police arrived. He was calm and threatened no one else, but when dozens of officers from multiple SWAT teams surrounded the house things got out of control. Amassing around Wood’s pickup in armored vehicles, with a helicopter overhead, the standoff devolved into chaos and Wood ended up dead. The police claimed he committed suicide.

The film follows Dub’s mission to uncover the truth, using his extensive investigatory skills, in both his son-in-law’s death and those of other, recent shootings in his community, looking at several cases where the no-knock search warrant laws, typical throughout the country, turned potentially peaceful situations into confusing, tragic outcomes. Yet the film is hardly a polemic against the police; the filmmakers talk with officers who were willing to go on record about their experiences in these raids, and the changing nature of their jobs that is taking place nationwide. Christopherson and Barber spoke to us about the timeliness of their film, making adjustments on the fly when Ferguson happened, and more.

So where were you in your process when Michael Brown was shot and killed in Ferguson?

Christopherson: We started two and a half years ago, we had wrapped production and were knee-deep in post and pretty close to finishing when Ferguson happened. We were so surprised this militarization of the police was happening in rural areas that we realized it must be happening everywhere, and then Ferguson confirmed that for us. After Ferguson we realized that our story acted as a microcosm for what was happening all over the U.S.

Many of these SWAT team raids appear, in retrospect, so galling and brutal. And considering SWAT teams in Utah have a pretty brutal track record, how did you get them to talk?

Christopherson: Some of the challenges with connecting with the police officers was we had to pitch the film to them almost as if they were Hollywood execs. It was intimidating at first. I took one of the commanders of the raid to lunch and talked about his experiences in shootings, and we did a pre-meeting with almost all of the officers to talk to them and earn their trust and build a relationship. For example, in the Matthew David Stewart raid [in which a SWAT team raided his house in the middle of the night, on allegations he was growing pot in the basement, and Stewart, an veteran suffering from PTSD, assumed they were breaking in and exchanged fire, killing one of the officers–he later hanged himself in his jail cell], the commander took me to meet all twelve of the officers involved, and they grilled me for two to three hours. In the most sincere way possible, I explained that we really wanted to put the audience in their shoes and let them know what it feels like to put your life on the line. We wanted to show them what it’s like to be involved in a raid. Out of those twelve officers, only two were willing to participate in talking about that particular shootout, but you see several other sheriffs open to talking about it. I think for us we always wanted to be compassionate to them, not villianize them, to show they’re humans and they’re put in these situations that are very difficult. We have a great respect for law enforcement, and one of our angles has always been that if we can find a way to protect the lives of officers and citizens, that would be the goal.

Do you feel like there’s hope for improvement with the way SWAT raids are conducted?

Barber: I hope there’s a teachable moment at the end of this. As we show in the film, Utah is currently the only state that tracks the use of swat teams, and that’s a pretty recent development that just started last year. Maybe it took Ferguson to get there. There should be public oversight for how swat teams are used. If Utah can do it, other states can do it, too.

Christopherson: We didn’t set out to make a film about the militarization of police. We meet Dub, then all of these things started happening and we became more aware. It was a learning experience for us, and I want to believe there’s hope in influencing policy and lawmakers to make a change for the better. If that means something as simple as body cameras on police, that would be great. In Utah, they have the government records access management act, which means that as a citizen you can request things like dashboard cameras or body cameras or evidence from cases. Things like this make the citizenry more aware.

What was it like working with Dub?

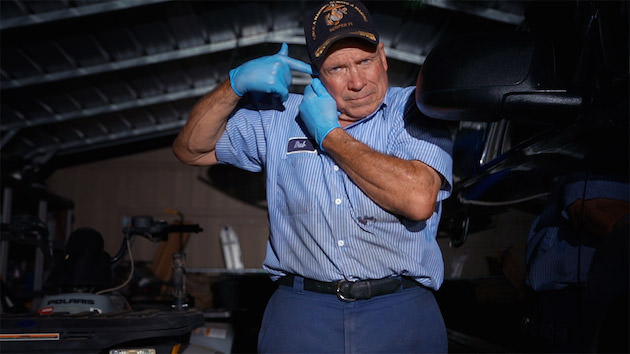

Barber: It was really inspiring. When he goes into a crime scene, you see him analyzing where and how things happened, he’s almost 71, but he’s so sharp and he comes alive in this really interesting way when he investigates a scene. There’s so much meticulousness and care, he was just completely dogged and tireless. He’d call us and say, ‘Okay, I figured out something else, I’m going back!’

Christopherson: Certainly, with someone so invested and passionate about it, it was actually a challenge for us. We had creative control over directing this film, and Dub understood that, but I think for me this film was especially draining throughout just because Dub has been through so much. You get to know and love our subjects, both police, citizens, and especially Dub, and you see in a sense this PTSD he has from seeing so many horrific cases throughout his life. By proxy, as a filmmaker, it took its toll on me and it was draining to see someone you care about, all of these characters, go through something so horrific and difficult. It was hard for me to see so much pain and suffering on all sides, especially with Dub. It’s certainly not a light film–he really wades through this shit.

You have two very passionate forces on either side of this story; the police and the people who lost loved ones in their raids. How did you manage working with both?

Barber: We didn’t want to alienate or antagonize one side against each other any more then they already are. The people we filmed on both sides really impressed us with their ability to be compassionate to each other. Liz, Brian Wood’s widow, talked at the end of the film about how she feels compassionate for the particular officer who pulled the trigger and killed her husband. There’s another part of the film where the parents of Officer Francom, who was killed during the raid against Stewart, neither of them talked bad about him, at least not in front of us. They talked about their son and how they felt about the officers, and those things give us hope. We believe in the power of documentary being an empathy machine, and that would be a great outcome of this film.