The One Tech Platform Used in Game of Thrones, Avengers: Endgame & (Much) More

From a remote outpost in Adelaide, Australia, a handful of techies in 2005 brought together far-flung filmmakers so they could critique VFX shots—not in the same room, but on the same screen. Today, cineSync software plays a behind the scenes role in nearly every spectacle-driven popcorn movie including this summer’s Men In Black, Spider-Man, X-Men and Godzilla sequels as well as recent hits like Avengers: Endgame and Game of Thrones. Cospective CEO Rory McGregor, whose company developed the Engineering Emmy award-winning technology, said “Game of Thrones is a great example of how cineSync pulls VFX teams together. In Season Seven they filmed certain shots from that huge frozen lake battle in Iceland at the same time they were shooting the “loot train” sequence in Spain. During post-production, you had maybe half a dozen visual effects companies based in Australia, New Zealand, the US., Canada, The UK, Spain.”

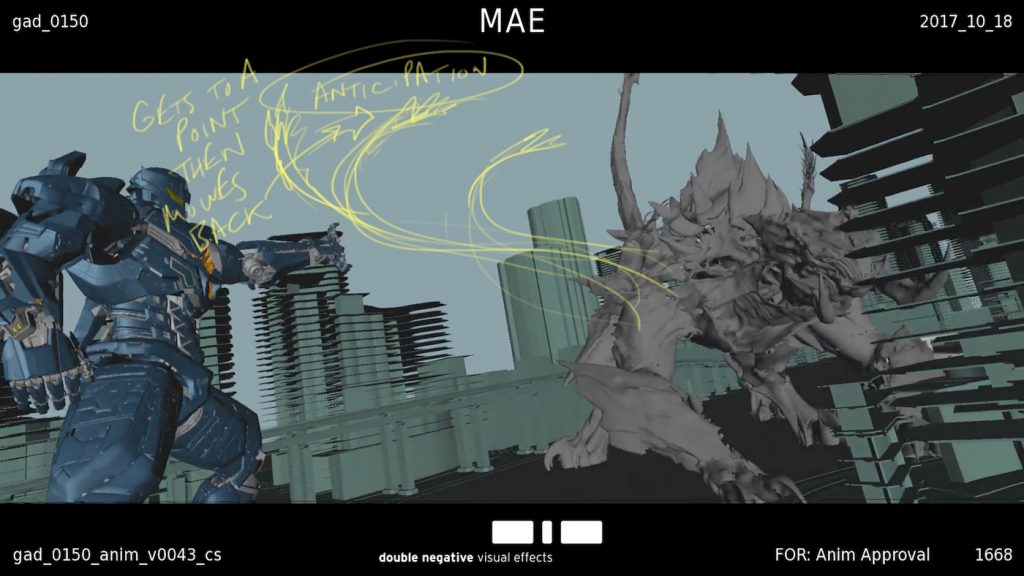

This season, the sheer quantity of dragon shots compelled geographically disparate GOT vendors to collaborate via cineSync, according to Game of Thrones visual effects associate producer Adam Chazen. “There were more dragons than we’ve ever had before in our final season,” Chazen said in a separate interview. “Image Engine did a lot of the dragon animation and then they’d share the animation caches with all of the other vendors working on the shot.” McGregor elaborates: “Think of it like spokes in a wheel. We have synchronization servers in different locations around the world. So if you have ten licensed users logged in from their desktops to our servers for a session, that’s ten machines showing ten reviews of the same shot. For example, a director can type notes into a frame: ‘Make this lighter.’ You can use a slider to change the color, or draw on an image to make adjustments, or circle some background element you want to remove or re-rack the shot to show more of the sky and less of the ground. When one person makes a change, the server propagates that change to everybody else.”

Not that long ago, VFX artists from different countries often contended with spotty connections and out-of-synch footage if they tried to collaborate remotely. Visual effects work on Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire and Superman movies stretched filmmakers’ patience to the breaking point and inadvertently inspired the quick fix that would become known as cineSync. McGregor explains, “Warner Brothers produced both shows and there were continual breakdowns in communications when people tried to clearly articulate feedback on the shots. Had it continued, the frustrations could have become a crisis.”

In response, cineSync engineers at Cospective, then known as Rising Sun Research, hacked a solution over the course of one intense weekend. “The platform that we built mashed together Quick Time Player and some chat room code into this core product,” McGregor said. “Industrial Light and Magic also worked on those shows so they had a copy and from there, cineSync took off. Steven Spielberg used it on War of the Worlds even before we commercially released the official version, which propagated by word of mouth throughout the film industry quite quickly.”

CineSync’s ascent has coincided with a 21st century diaspora of VFX shops, motivated in part by tax rebates, that feed production pipelines 24 hours a day across multiple time zones. To prevent leaks to spoiler-hungry movie fans, cineSync time-matches movie files for licensed users while maintaining a strict hands-off policy regarding the content embedded inside those files. “We don’t touch the media and have no access to the content, which is one reason we’ve been embraced by the industry,” McGregor says.

Creatively neutral by design, cineSync aims to spark epiphanies for remotely connected users. McGregor, whose Cospective team won an Academy Award for Technical Achievement in 2011, says “Being based in Adelaide, which is not exactly the center of the filmmaking world, it’s been fun to develop a platform that encourages the free flow of ideas between filmmakers so they can challenge themselves: ‘How far can we push this? How far can we go to make things visually interesting?'”

In the realm of visual stimulation, little details can make a big difference, like the time a prank VFX shot helped give birth to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. McGregor explains, “For Iron Man, as a joke, one of the VFX artists put Captain America’s shield in the background of Tony Stark’s workshop. During the review session, director Jon Favreau saw the shield and thought it was funny so he decided to leave it in and see if anybody else noticed. They did, and it became a thing where people started asking how a shield from a 1940’s character could show up in Iron Man’s workshop. That moment came out of a creative visual conversation, whereas if they’d only been talking on the phone like we’re talking now, that idea probably wouldn’t have happened.”

L-r: Chris Evans is Captain America in ‘Avengers: Endgame.’ Courtesy Walt Disney Studios. A shot from episode 5 in season 8 of ‘Game of Thrones.’ Courtesy HBO