Trial by Fire Director Edward Zwick on Revisiting a Heartbreaking Story

Cameron Todd Willingham, who’s played by British actor Jack O’Connell in director Edward Zwick‘s Trial by Fire, was not an exemplary character. But he almost certainly didn’t set the 1991 blaze that killed his three young daughters, an alleged crime for which he was executed by the state of Texas in 2004. The fire was likely accidental, as was demonstrated by the evidence presented in David Grann’s 2009 New Yorker piece and Incendiary: The Willingham Case, Joe Bailey, Jr., and Steve Mims’s 2011 documentary.

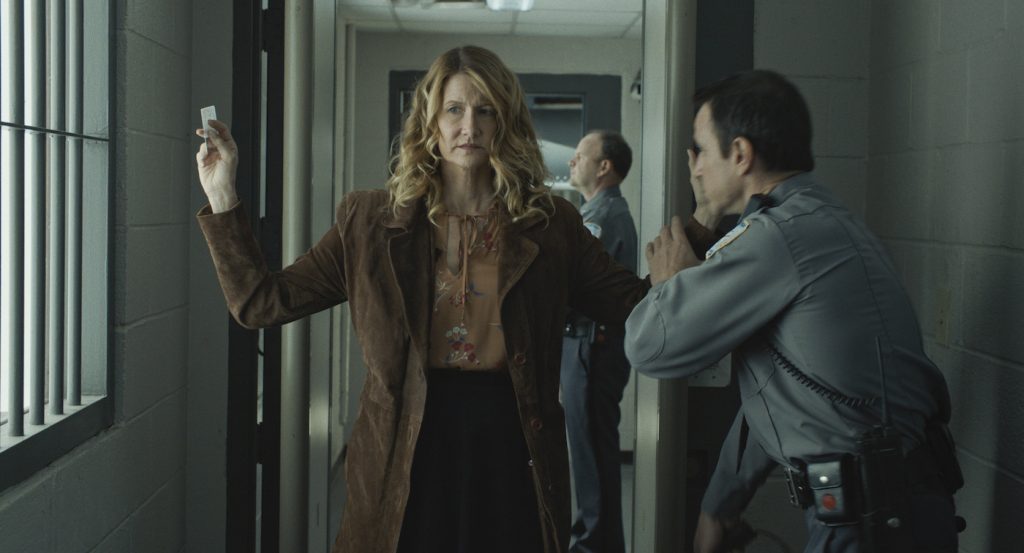

Zwick visited Washington recently to promote his dramatization of the case, in which Laura Dern plays Elizabeth Gilbert, a Houston playwright who campaigned without success to get Willingham a new trial. In his interview with The Credits, which has been edited for length and clarity, Zwick discussed how and why he made his latest movie, which opens May 17. He began by explaining how he approached telling a story that had already been recounted in a nonfiction film.

“I saw two opportunities. One was that when you put a human face—which is to say an accessible dramatic experience—on a true story, there’s the possibility of reaching a different audience. Of having it land and penetrate in a different way than documentary. That is by no means to diminish the power of documentary, which I love, and watch avidly. I think there’s a place for each. But often, for better or worse, narrative film becomes part of the permanent record. And sometimes a larger part of the permanent record…

“The other thing is that I found the relationship between Todd and Elizabeth to be very compelling. As I met Elizabeth and read her correspondence with Todd, I felt there was something else that could be told about these two people and their unexpected and very important relationship. That’s very different from what the documentary sets out to do.”

Is it fair to say that you prefer protagonists who have difficult pasts?

I’m trying to think. I’m going through my own movies here. I guess I’ve done that more than once before. But not always. Can’t say that of Robert Gould Shaw in Glory. I could say that of Bobby Fischer, God knows. Let me think. The character in Courage Under Fire, yes.

The Last Samurai.

OK. Your point’s made. [laughs] Look, is that a dramatist’s impulse, or is it something more personal? I guess it’s both. I am interested in redemptive sagas. In this particular case, had he been an utterly sympathetic figure, it might have rendered it sentimental. This man was disreputable but nonetheless did not deserve what he got.

Watching Jack O’Connell play Todd, I thought I’d never seen him before. Afterward, I realized I’d seen him in several movies.

Maybe with a British accent.

Yes.

And you go, “Oh my God, that’s a great performance.” His dialect work here is quite brilliant. But what I think is really amazing is the willingness to show someone who is reactive and abusive, and has never been exposed to things that might be more redemptive. Which he finds in the relationship with Elizabeth. Which he finds, curiously and ironically, in prison. In books and in art.

So it had to be an actor who was willing to embrace those things. Some actors are self-protective. They’re just too concerned with the audience’s sympathy. He is clearly an actor who was willing to not do that.

How important was it to have Laura Dern opposite him?

I’ve known Laura for a long time. An actor can suddenly seem to have a moment, but those of us who’ve watched her know that she’s just done great work. What I know about her, that maybe was privileged, was that she’s been involved in activist causes. That she’s extraordinarily empathic. And she’s an amazing listener. I knew this was going to be a quiet performance in many ways.

The scenes where Elizabeth visits Todd in prison, where it’s the two of them alone in a little box, are like a theater piece.

That’s right. In fact, I kept them apart until that moment. We didn’t rehearse the prison visiting-room scenes. I wanted to bring them together, and then shoot it chronologically so they would have the experience of each other, as close as possible to approximating the characters’ experience of each other. I think that helped give it a certain sense of discovery.

Obviously, it had to be two actors who can handle a lot of words, and liked the theatricality of the two-hander. We did probably two of the scenes a day over four days. It’s the armature of the piece, the spine.

In the press kit, Laura Dern says of you, “As a filmmaker, he’s a writer first.”

I should look at the press kit. [laughs] That’s interesting. Look, this is with no disrespect to any screenwriter who’s worked with other directors, or who’s worked with me. But I think, at the end of the day, the director is writing the movie. He’s writing it with the camera, and with the staging and the interpretations. As well as with the words. And often the words change.

I’ve worked with some of the best screenwriters in Hollywood, and I’ve written for other people and for myself. The words become what they need to be, I find, organically. It’s what happens in the collision with the actors. And what the director brings, whether the director and the writer have adapted together. Even when I’ve been the writer of my own stuff and find things that so need to be adjusted as we go.

Before the shoot began, how did you work with screenwriter Geoffrey S. Fletcher?

Geoffrey is a really smart guy. We met a lot and talked. David Grann’s piece had one thing that was really so available to use. You meet the arson investigators and you hear them talking about the fire science with such certainty. I wanted the audience to feel that, too. I wanted the audience to be complicit in their judgment of Todd Willingham, as the jury was. So their experience would be active as Elizabeth investigates and as we discover that we were wrong. Because we were complicit in his condemnation, we have to then participate in the whole process. And that’s something Geoffrey and I talked about a lot.

The movie’s treatment of fire science, or fire not-science, dovetails with today’s controversies about pseudoscience, such as anti-vaccination disinformation.

That’s interesting. It’s funny about how you do a movie and it takes a certain amount of time, and then you find that contemporaneously it’s a different thing than you set out to do. History sometimes catches up to you. That happened when I made a movie called The Siege.

I also thought a lot about the demonization of Willingham. I look around at some very upsetting demonization that’s happening now. That seemed to be relevant. We have a need to identify the other and to get rid of the other. Particularly when there’s something that happened that is senseless. We try to make sense of it, and one of the ways we often try to make sense of it is by identifying a scapegoat.

This movie was financed outside the usual Hollywood system.

I did a movie called Blood Diamond. During it, I worked with a group called Global Witness, which is an organization in Britain. They were instrumental in the Kimberly Process, which helped create fair-trade diamonds and get rid of blood diamonds. They asked if I’d serve on the board, and I’ve been on the board since.

On the board, I met a young man, Alex Soros. He would ask what I was doing. I would invite him to the movies I’d done. It was just a friendship. He knew I was trying to do this movie, and he told me that the Soros Foundation was very involved in criminal justice reform. They financed an initiative in California to try to get rid of the death penalty, which failed.

He said, “Maybe I can help.” I said, “Don’t tease me.” [laughs] I’m Charlie Brown with the football, in terms of the number of times that people have said that.

I guess all directors are.

We are. But he said, “No, no, let’s sit down.” And we talked about what he could do. Without that help, it never would have gotten made.

When I interviewed the directors of Incendiary in 2011, they said they didn’t oppose the death penalty. Did you see that opposition as a crucial part of this film?

Maybe, yeah. I was casually opposed to the death penalty before I began, and I am now violently opposed to it. Because of what I’ve learned about the process.

What do you hope for people who see the film? That they’ll see it as an issue film, or as more of a human drama?

Is it possible that they would see it as both? That’s my wish.

Featured image: Jack O’Connell and Laura Dern in TRIAL BY FIRE. Photo credit: Courtesy of Roadside Attractions