First Man‘s Oscar-Nominated VFX Supervisor on Building the Biggest LED Screen Ever

*In the run-up to this Sunday’s Oscars telecast, we’re sharing some of our favorite interviews with nominees.

Watching Damien Chazelle’s First Man offers the earthbound viewer the chance to realize they don’t have the right stuff finally. For folks of a certain age, becoming an astronaut used to be one of the coolest possible professions, the kind of thing you said you wanted to be when you were little and didn’t know what engineering was. Or math. Or physics. And, most crucially, you didn’t realize how insanely dangerous it is. There have been many great films about space. There have been many great films about the plight of the astronaut in particular. These include Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity, Ron Howard’s Apollo 13, and Phillip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff. It’s fair to say that none have been as visceral as First Man. Damien Chazelle’s film captures the blood, sweat, and tears that went into making the Apollo 11’s historic 1969 mission to the moon possible. Strapping yourself to a rocket so that you might enjoy the most hostile environment known to man (should you survive the flight) is, practically speaking, terrifying. First Man straps you to that rocket and, like the G-forces working on Ryan Gosling’s Neil Armstrong, pins you there.

One of the people responsible for making sure the dangerous test flights, as well as the Apollo 11 mission to the moon itself, was as riveting and tense as possible was Oscar-winning VFX supervisor Paul Lambert (Blade Runner 2049). Once Lambert joined Chazelle’s team, the young director sent him a 300-page PDF outlining the entire film.

“I’ve never had access to this kind of thing before,” Lambert says. “It just showed why he’s one of the top filmmakers in the country. This PDF outlined exactly what he was thinking, down to specific sounds and visuals, and what he wanted it to feel like. I’ve never experienced something so open like this.”

Lambert had a novel idea for approaching the visual effects, and it required making his job immensely more difficult.

“I explained to Damien how I’m a big fan of not trying to break things down into various levels in VFX and then recombine them in post-production,” he says. “I’d much rather put as much effort into the camera knowing that it’s going to be a much harder composite later, and doing the work myself. I know you’re always going to get a better result this way. Yes, it’s going to hurt more, but you get a better visual.”

Chazelle wanted First Man to have a documentary feel, which is always tricky for the VFX crew because it means the camera’s ceaselessly moving, and a moving camera makes it harder to capture the information that the VFX team needs. Luckily for Lambert, Chazelle had spent years thinking through First Man (screenwriter Josh Singer told us they began talking about the film before Chazelle La La Land) and had visuals ready for Lambert to peruse.

“Damien sent me an animatic [a preliminary version of a movie created by filming successive sections of a storyboard] of the X-15 flight and the Apollo launch,” Lambert says. “Incredibly, it included pieces of Justin Hurwitz’s score—this was all before the first shot was made! I found that to be incredible. We were going for a visceral feel,” he says. “We knew we had to produce the visual effects in a way that wouldn’t take you out of the movie. We knew we were shooting with 16mm, 35mm, and IMAX [for the film’s climatic lunar sequence]. So we came up with a few guiding principles; we were going to use miniatures, we were going to use archival footage, we were going to use an LED screen, and we were going to use full-scale builds of certain ships.”

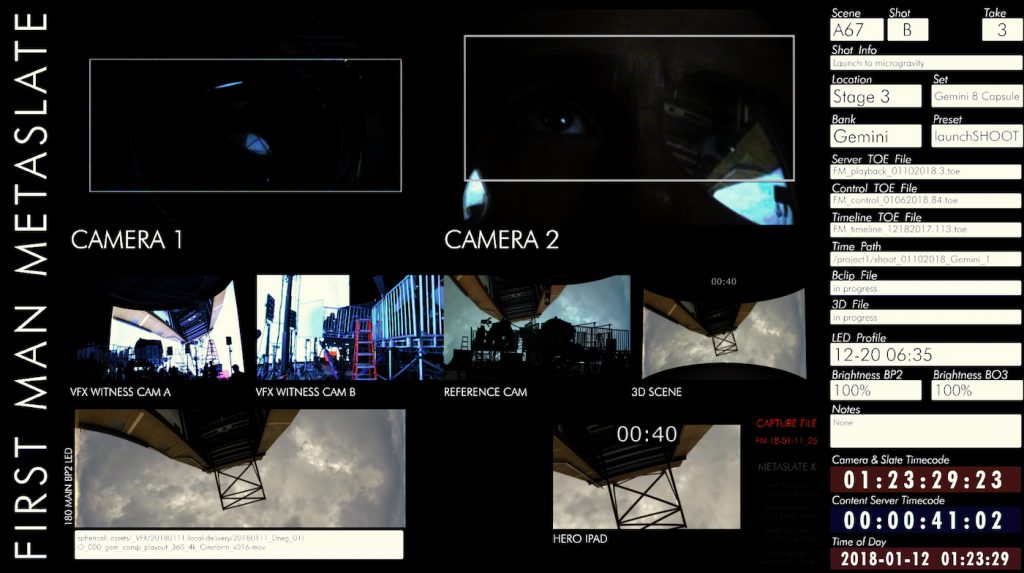

That LED screen became the biggest ever used on a film, with 90 minutes of rendered footage captured on the spherical behemoth.

“The LED screen was pivotal for our VFX work,” Lambert says. “We built this 35-foot tall, 60-foot wide, 180-degree circular screen. We’d project content onto the screen that you’d see through one of the capsules or cross mounted shots, so what you see through the camera is what you see in the film. We were trying to redefine what ‘in camera means. That’s a term that’s used a lot today, which means you tried to avoid using any CG, but what we were able to do with this LED screen was get subtitles into the film that you’d usually need a green or blue screen to achieve.”

The results were evident in the thrilling X-15 test flight, in which Gosling’s Neil Armstrong pierces the atmosphere and makes it into space, only to bounce off the atmosphere and nearly die in the process.

“When Ryan’s in the X-15 and breaking through the atmosphere and you see the horizon line on his visor, that’s the actual reflection from the LED screen,” Lambert says. “What’s more, you also see the reflection in his eyeball. If I had got that shot on a blue or green screen, I’d have had to spend a lot of time trying to get that visual, and I know I’d never get it exactly as I got it ‘in camera.’ Thanks to the LED screen, we didn’t do any post work on that particular shot. No additions were added to it, and that was the guiding principle for a lot of our work.”

This approach allowed Lambert and his team to fulfill one of Chazelle’s main objectives; to film entire sequences rather than shooting bite-sized moments ultimatley rendered for VFX. This made Lambert’s job more difficult, but the results speak—and sparkle—for themselves.

“It was a huge undertaking,” he says. “We had an entire section of the X-15, from when it drops from the B-52 to when it lands—that’s all one sequence. Damien wanted to do it that way so he could do long takes with Ryan, who was in a full-scale cockpit on a gimbal all day. I didn’t exactly envy him, we shook him in that cockpit for the entire day. We filmed these major sequences all in one section; the entire Gemini launch as they’re going through the clouds; the entire Apollo launch as they’re going up to the first stage of space; and the entire run to the approach of the moon. We had built that world so it could be projected on the LED screen, so if the ship was banking or turning, we were able to program that on the day. This was huge. The actors could then see where they are at any given moment. They could see that they’re up in the clouds, or they’re just piercing the atmosphere, or approaching the moon.”

Then there was the second novel approach to making First Man‘s flight sequences feel as real as possible. Lambert’s team found and fine-tuned archival footage. The First Man crew learned that every Apollo launch included a bunch of engineering cameras trained on different parts of the ship. These videos, which captured the exhaust or a clamp or a part of the rocket, were created in case there were any accidents so that NASA scientists and engineers could see what went wrong and try to fix it. NASA stored the footage in military bases throughout the country, and First Man producer Kevin Elam tracked them down. Some of them were then handed over to the VFX team to make them work in the film.

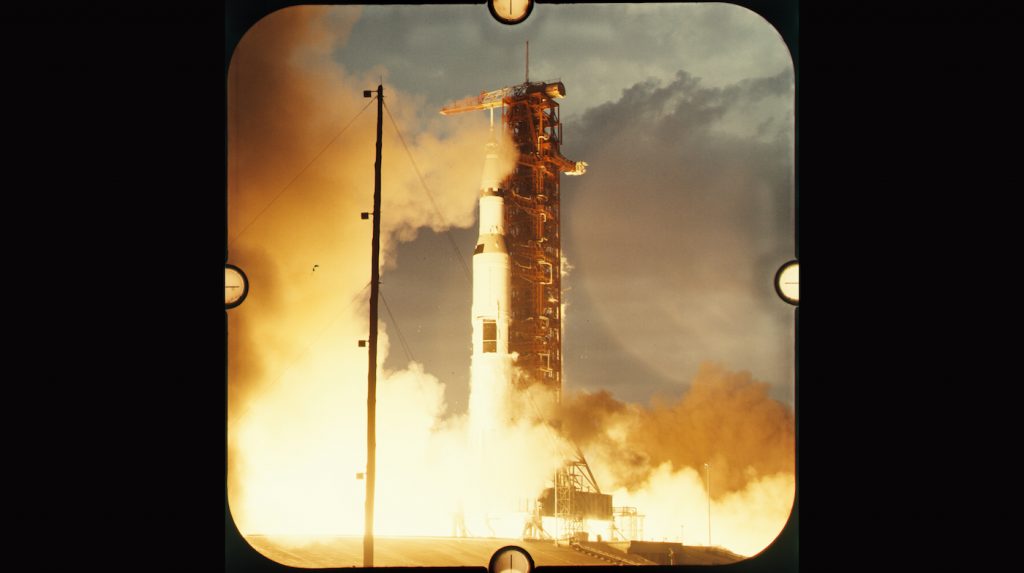

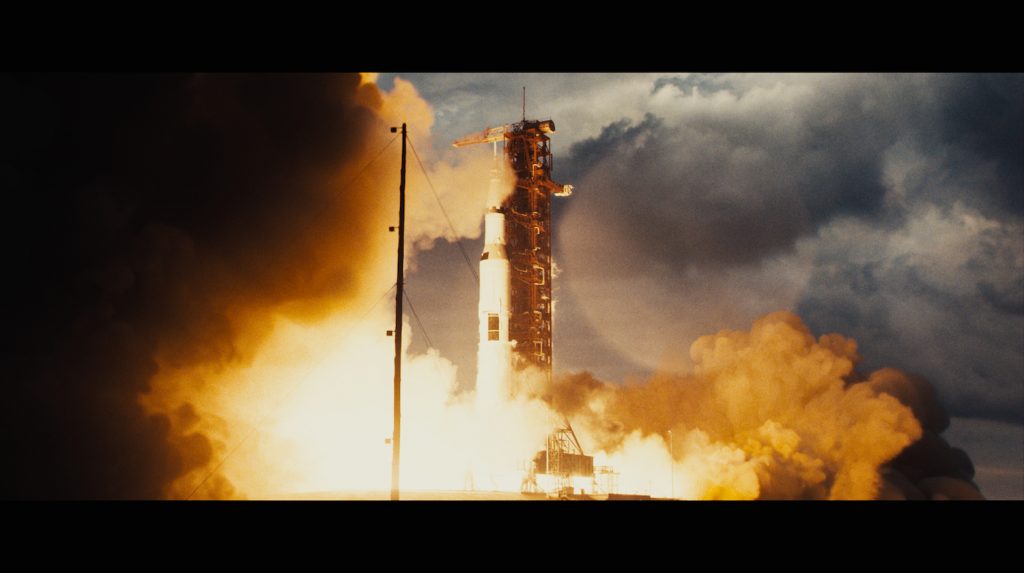

“Some of the stock was on a NASA 70mm stock footage,” Lambert says. “You couldn’t play it back anywhere, and we spent ages trying to find something we could scan the stuff with. We finally came across a place in London with an experimental scanner that you could scan sprocket-less film, so we got this archival footage and played with it. Damien didn’t want anything in slow motion, so we sped up this old footage, cleaned it up until it looked super sharp, then we were able to degrade it to match the visuals of First Man as if it had been shot on the day. So there are various shots in the launch sequence where we used this old footage. One of my favorite shots was a cleaned up 70 mm shot of the Apollo 14 that we added CG smoke to make it more cinematic. Taking archival footage and adding CG to it to create something new was a novel approach. Nothing stands out as being a visual effect, even though you know the effects are there.”

And finally, some of the film’s remarkable effects were created much in the same way a child might pretend he’s walking on the moon—good old fashioned playfulness.

“When you see they’re out in the Apollo craft and it looks they’re like weightless, while we did use wires on a few shots, we also used a very old technique—we had the actors stand on one foot and pretend to float, and it works so well [laughs]. There are quite a few shots when Ryan or Corey [Stoll] is on one foot pretending to float. We used every technique in this movie.”

First Man is in theaters now.

Featured image: Final Composite of Apollo 11 launch. We augmented archival 70mm NASA footage of the Apollo 14 launch. To create a more cinematic visual we reframed it, cleaned it up and the extended the sides with CG smoke and sky to match. Courtesy Paul Lambert/Universal Pictures.