Celebrating the ASC’s Top 10 Films of the 20th Century

The American Society of Cinematographers recently released their “100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of 20th Century.” For the uninitiated (which is 99% of the viewing public), the ASC is “an honorary organization made up of the best cinematographers in the world,” says cinematographer Richard Crudo, ASC (this explains why you often see an “ASC” after a cinematographer’s name in the credits.) “Membership is by invitation only and is extended after the candidate has been proposed by members and has passed a screening process.”

The titles in the ASC’s list were compiled through an internal poll conducted by the Society. “I believe that gives it a special significance because it reflects the opinion of an unusually well-qualified group of people,” Crudo says. Yet he also acknowledges, “It’s only an opinion. There are so many great films on the list that I don’t think you could argue with any random ten of them being placed at the top.”

But indeed, ten were placed on top, and those were ranked, which brings us to our business here. The top ten is as follows, in order: Lawrence of Arabia, Blade Runner, Apocalypse Now, Citizen Kane, The Godfather, Raging Bull, The Conformist, Days of Heaven, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and The French Connection. Let’s dig in.

One of the Greatest Entrances in Film History

While Star Wars‘ didn’t make the cut, if you’re curious as to where the conceptualization of filming the broad desert vistas of Tatooine came from, look no further than the number one entrant – David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. The legendary film was shot by Freddie Young, BSC (the British Society of Cinematographers) on Super Panavision cameras that were hauled into the sands and hills of Jordan and Morocco (and later Spain). This where they recreated the WWI-era story, with the crew would sometimes finding itself as isolated in the desert as the original Lawrence was.

The film remains distinct, with its sun-dappled widescreen look, from many of the shadow-strewn films it shares the list with. It does share some of the hallucinatory aspects seen in the river journey in Apocalypse Now—in the sense of reality emerging from a mirage.

This would be the entrance of Omar Sharif. Peter O’Toole’s Lawrence and his guide are at a well. Out of the desert heat, impossibly far away, is a rider. He doesn’t ride a horse, but a camel.

The suspense grows—is this is a friend or foe? There is one quick cut in the middle to briefly compress time, but otherwise, we are waiting almost in real time with the actors. Even Maurice Jarre’s iconic score is missing, as the ambient sound ratchets up the tension. It remains perhaps the greatest screen entrance a new actor has ever had.

Magic Hour

Of course, the alchemy of the cinematographer’s art is also a collaborative effort, as movie making always is. Or as the late Haskell Wexler said in an interview on Roger Ebert’s website, “what’s in front of the camera is not just what we do through the lens…the wardrobe, the grips, all that are part of what we do. And that’s not to make me sound like some generous guy, but actually, that’s what photography is.”

Wexler knows that of which he speaks. He shares credit on Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven. The film is credited solely to cinematographer Nestor Almendros (ASC), but he actually had to depart halfway through production, leaving Wexler, with an “additional photographer” title, while Almendros took home an Oscar. Wexler wasn’t bitter. He believes Almendros deserved the award for establishing the “magic hour” motifs of waiting to shoot most of the film during dawn or sunset. This gave Days of Heaven its stunning hues, which erupt in what may be the movie’s most memorable sequence—an out-of-control prairie fire sparked in a vain attempt to control an invasion of locusts.

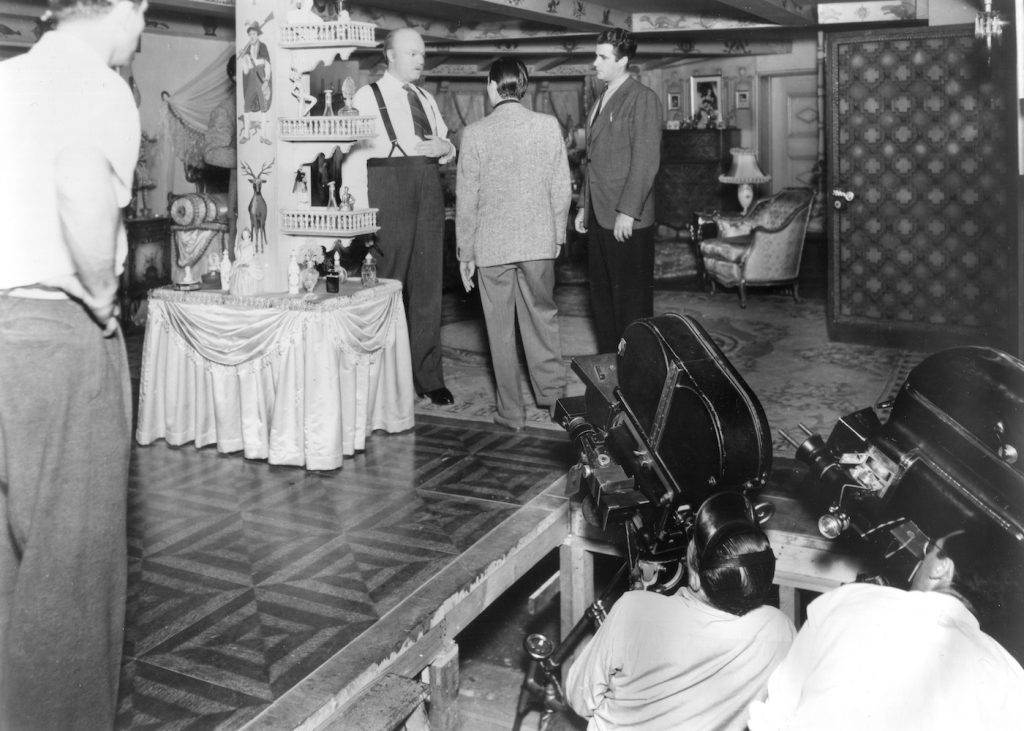

Changing Cinema Forever

The oldest film in the Top 10, Citizen Kane, was also one of the most inventive. One of the many novel approaches Orson Welles and his team took was sawing away floorboards in order to rig cameras. Cinematographer Gregg Toland (ASC) wrote in an issue of Theater Arts magazine that every set in the film “was provided with a complete ceiling, an unheard-of procedure in set construction but one which opened up entirely new possibilities in camera angles.”

So consider every ceiling that you see in Citizen Kane as the innovation that it was, in terms of camera placement, lighting, and more. Toland’s extreme depth-of-focus, with foregrounds and backgrounds staying equally sharp, was also both innovative and startling. The famous shot—but aren’t they all?—of Welles as an elderly Kane, trapped in his palatial Xanadu, walking by a mirror which is then infinitely reflected in an unending row of mirrors, becomes, in a sense, a meta-commentary on what Welles and Toland are up to. They are providing infinite reflections that had never been available quite like that on a screen before.

Shadow & Light

Francis Ford Coppola was greatly influenced by Bernardo Bertolucci’s period piece The Conformist, and the way cinematographer Vittorio Storaro (ASC) lit the story of Jean-Louis Trintignant’s repressed cipher seeking to find “normalcy” in an arranged marriage and membership in Italy’s growing fascist party.

Storaro played with shadow and light to such an extent that some of the scenes almost feel accidentally underlit. They were, of course, shot in such a way to evoke the deep, darker waters beneath the veneer of what appears on the surface like a fairly normal environment.

The play of light and shadow is exactly how Coppola wanted The Godfather to look. In his collaboration with cinematographer Gordon Willis(ASC), we have Brando’s Vito Corleone in slats and shadows as he takes kudos and requests in his office on his daughter’s wedding day.

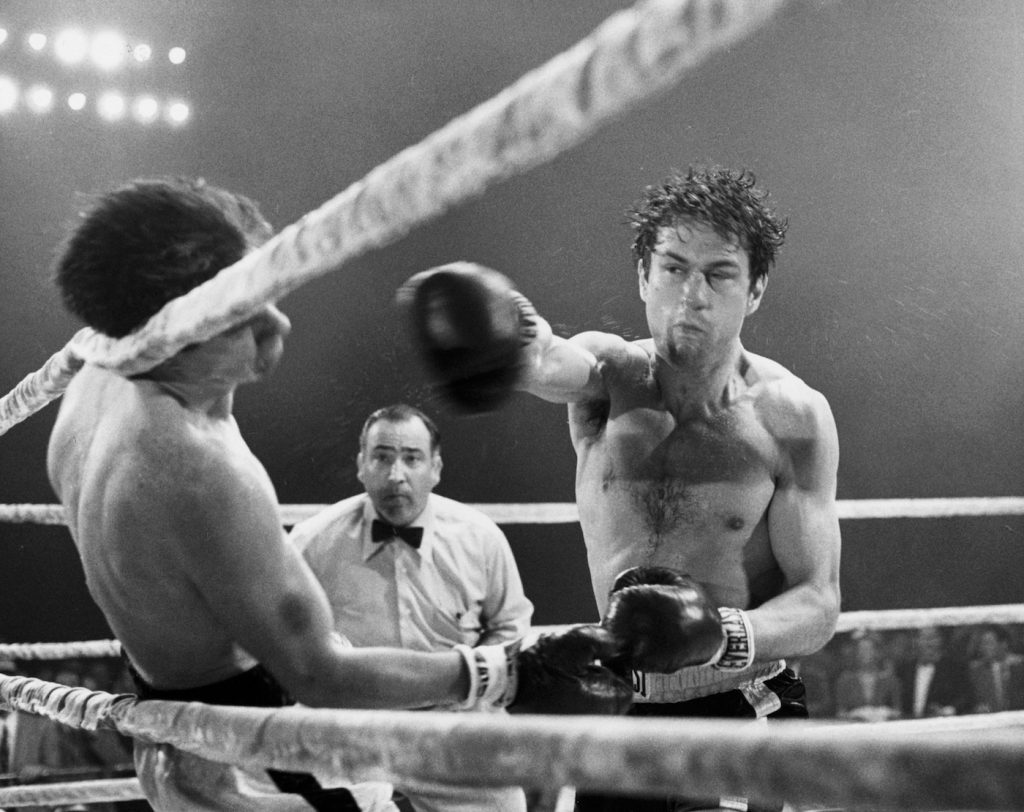

Brando’s face would again be introduced in even more profound darkness when Coppola finally collaborated with Storaro on Apocalypse Now, as Martin Sheen’s Captain Willard finally arrives upriver. Martin Scorsese uses a similar approach for one of the most affecting moments in Raging Bull, shot by his Taxi Driver collaborator Michael Chapman (ASC).

The first half of Raging Bull looks like 1940’s-era crime photographer Weegee shot—replete with flashing bulbs in the ringside scenes—that changes once boxer Jake LaMotta (Robert DeNiro) finds himself in a Florida prison on a vice charge. LaMotta smashes the wall with his fists, sobbing that he’s a man, not an animal. And in the end, all we see peeking out of the darkness is part of one arm.

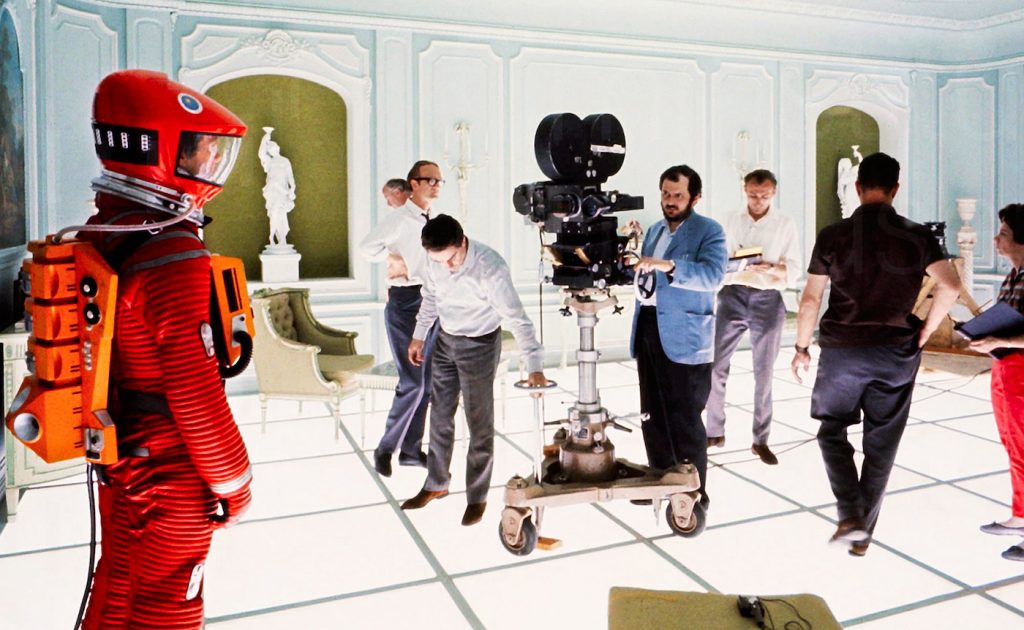

Re-Defining Sci-Fi

Technically the only “neo-noir” on the list is Blade Runner, with cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth (ASC)’s smokey, hazy shots collaborating so stunningly with director Ridley Scott’s sense of rain-slicked streets and prevalent neon. But we’re back to shadow and suggestion again for perhaps the film’s spookiest sequence—when both detective and replicants arrive for the final showdown at the at the salvaged loft home of robot-and-toy designer J.F. Sebastian.

It’s also the only other science fiction film near the top along with Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was shot both by the BSC’s Geoffrey Unsworth (BSC) and John Alcott (BSC).

Unsworth and Alcott worked with the director in essentially ushering in the era of “modern” visual effects, including Unsworth’s use of a Polaroid camera shooting black and white ASA 200 film to get the lighting setups, since they were not only shooting into practical lights, but needed to everything to be as absolutely crisp as possible. This was because Kubrick wanted to minimize the standard FX technique of using traveling mattes for spaceships, to preserve that “you are there” sense of the imagery which still holds up to this day.

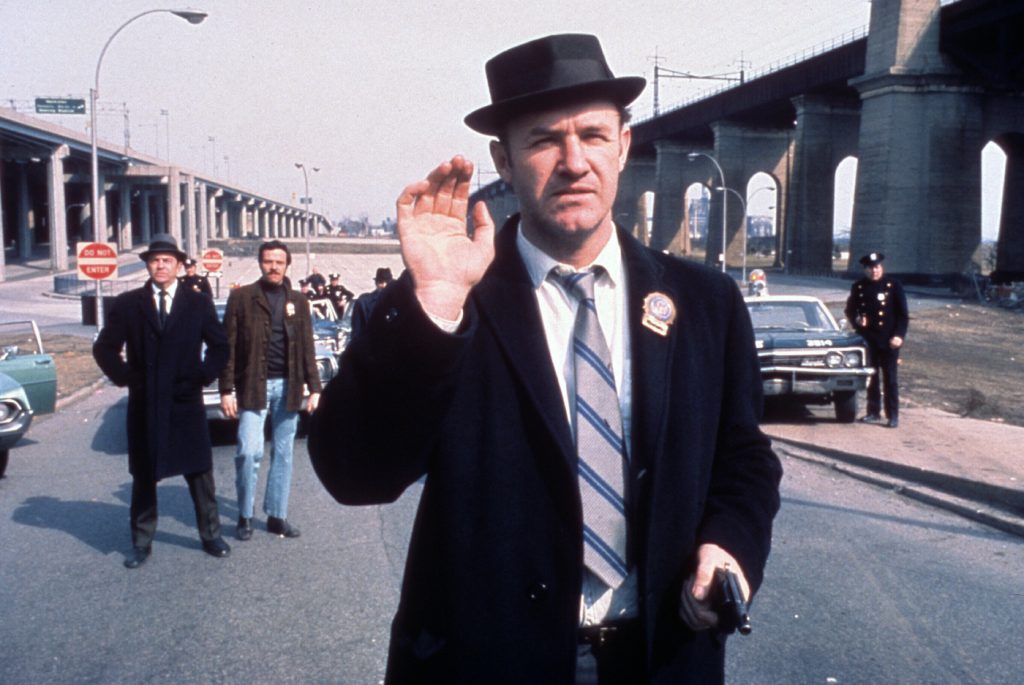

The Great Car Chase

Number ten on the list, The French Connection, contains one of cinema’s greatest car chases. Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle is rampaging under an elevated train as he tries to track down a French drug runner. The scene is also a credit to stunt driver and chase designer and Bill Hickman and editor Gerald B. Greenberg—who won an Oscar—for their work. But of course, it was cinematographer Owen Roizman (ASC) jury-rigging that fabled Pontiac, tearing out seats and mounting cameras inside the car (with the director wielding one from the back seat!) making it even more visceral.

“The landscape of 20th-century cinematography was so rich in so many ways that we felt compelled to give it its own moment in the sun,” Crudo notes, perhaps inadvertently referencing that number one pick. “No distinction was made between film or digital—it’s just that the sheer volume of the work was overwhelming on its own. Next year will already place us twenty years into the new century. We’ve certainly seen our share of masterpieces since 2000 and I should imagine that a new poll might not be very far in the offing.”

Hopefully, we won’t have to wait eighty more years for it. That would be a very long camel ride, indeed.

Featured image: A scene from ‘2001: A Space Odyssey.’ Courtesy ASC/MGM.