Oscar Watch: Barry Jenkins on his Lyrical Adaptation of If Beale Street Could Talk

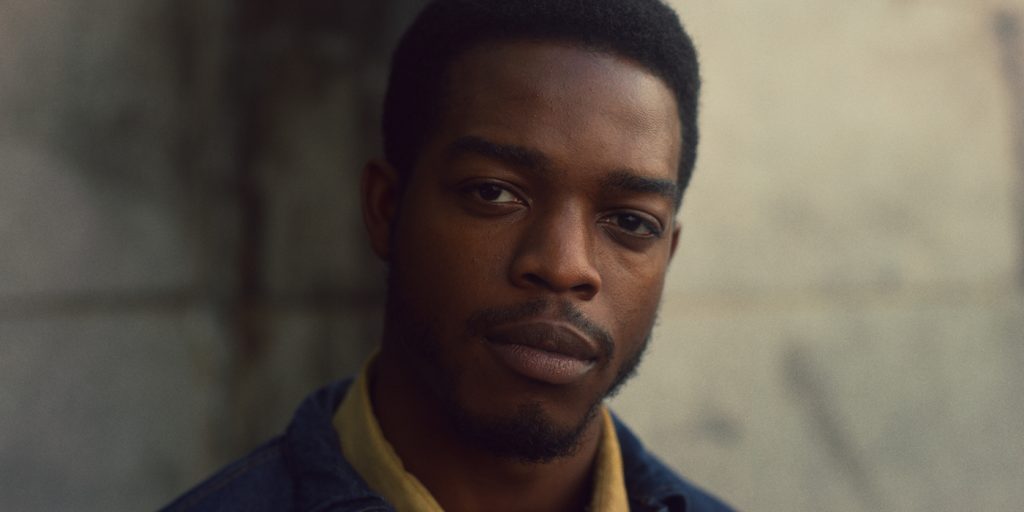

If Beale Street Could Talk has been getting awards buzz and accolades for months, and with the Golden Globes set to arrive this Sunday, Barry Jenkins second masterpiece (in a row, no less) will be one of the night’s big winners. Still hot from his 3 Oscar wins for Moonlight, Jenkins is reaffirming he’s a major force in film, with Beale Street already winning or nominated for dozens of awards, including being named Movie of the Year by the AFI. An adaptation of a 1974 novel by James Baldwin, the story is set in 1970s Harlem, and is about young lovers Fonny (an excellent Stephan James) and Tish (dynamite newcomer Kiki Layne), who are struggling to prove Fonny’s innocence (he’s been accused of raping a woman, something that would have been impossible for having to have done, logistically and psycho-emotionally, considering the man he is) all in time for the birth of their child. The Credits spoke to Jenkins about working in Hollywood, his visual influences for this project, and how his desire to connect with his audience informs his choices as a director.

How did you get connected to the Baldwin estate and get approval to bring this novel to the screen?

James Baldwin’s legacy is very important and very protected. It wasn’t like there was one person to grant me the rights. The family as a unit had to agree that this was something that was going to be worthwhile. I think the fact that I wrote the book without the rights was beneficial.

There’s so much narcissism in the film industry. It is almost expected from auteurs or directors with a strong point of view, yet everyone you work with says you are very collaborative and nurturing, and in your work specifically, with the level of vulnerability and trust required, there’s no room for it. How do you get out of your own way in such an often inauthentic environment?

I think it’s been a process of how I learned about film. In a film school environment you have to do everything, and so you go from being the director to being someone’s boom operator. I realized really quickly that I was learning a great deal from the people I was making my short films with, in film school in particular, which is why I’m still working with them today. My cinematographer, my editor, and my producer are all people I went to film school with. On Medicine for Melancholy, you’re really seeing how much (actor) Wyatt Cenac brought to the film, just by just allowing himself to truly embody the character. On Moonlight, there was a limit on how far my own experience dovetailed with the many characters’ experiences, in that I had to allow the characters the space to truly express themselves in the film. I think it’s been through my experience, which I’ve been very fortunate to have, that has reinforced that I can’t be an egomaniac. I have to be someone who plays nice, and trusts my collaborators and empowers them.

Harlem feels such an essential part of the film, it’s like a living character, and the visuals recall the photography of Gordon Parks and Roy DeCarava. What were some of the influences that brought the look of the film together?

This movie, unlike Moonlight, was meant to be a portrait in a certain way, and when we were looking up, doing visual research, the majority of what we found was still photography, so it was a lot of Parks and DeCarava, and Dawoud Bey, who was a generation later, but still Harlem-based. It was just this idea of trying to find a way to root the audience in an authentic experience of what Harlem was, which we didn’t truly have the budget to do, in a way that maybe in a pie-in-the-sky way you sort of want. So we thought, it’s a Harlem of faces. We allowed the visual research to inform so much of what we were doing, we even used this 2 x 1 aspect ratio as opposed to 2.35 or 1.85, because it’s close to portraiture, but still cinematic. Even the Alexis 65, which is sort of a medium-format camera, informed so much of what we were doing. So that was our primary visual inspiration, these still photographers, and pairing that with the literal syntax of the way Baldwin wrote. This book is very detailed and expressive in the way he is describing things, and we felt it was safe and ok to allow that expressiveness to inform the way we framed the images, even through this portrait lens.

What is it that attracts you to asking the audience to engage with and witness intimacy? When you center the characters in the frame, they are asking us to be engaged with them, and be connected to them.

It’s something we stumbled into on Moonlight, and it came from a very visceral place. It was a scene with Naomie Harris, where she’s in the throes of her addiction. It felt unfair that the audience was allowed to exist outside that sequence, because I had a personal connection to that, and I was feeling things, so to me it was about creating a moment of direct engagement. It wasn’t an intellectual thing, it wasn’t an artistic thing, it was a very personal, visceral thing, that has now become an intellectual tool because I do think it works in the way that you’re describing. I think when an actor is performing as a character, there’s a bit of distance between them and the character. There has to be. They know that they are performing, but I think there are moments the actor and the character kind of fuse in this way where it’s just one being. That’s when I want the audience to directly connect to the person onscreen. We don’t plan them, and it’s why they rarely have dialogue. If you are performing dialogue, you go back to being removed. It is about not forcing the audience, but if they are willing, allowing the space for the audience to directly connect with the character. This idea of intimacy, that’s where the power of cinema is. You read a novel, and all the voices are in your head, but you walk in the cinema, and these actors are there. Two dimensional, but they are there. Then this idea of empathy, and linking between the audience and the characters, and between myself, Mr. Baldwin, and you guys, that thing becomes so potent, so intense, that you can’t walk out of the room and not say that you didn’t meet these characters, and you didn’t feel what they felt. Once you feel what they feel, you can’t deny it. Their issues become as important to you as they are to them.

Featured image: (l to r.) Actor Stephan James, director Barry Jenkins, and actor KiKi Layne on the set of IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK, an Annapurna Pictures release. Photo by Tatum Mangus / Annapurna Pictures