Oscar Watch: DP James Laxton on Creating Radical Intimacy in If Beale Street Could Talk

Oscar-nominated cinematographer James Laxton (Moonlight) and his longtime collaborator director Barry Jenkins did something novel with If Beale Street Could Talk, and we’re not just talking about the fact the film is adapted from the legendary James Baldwin’s titular novel. Unlike their previous collaborations, 2008’s Medicine for Melancholy, set in San Francisco, and 2016’s Oscar-winning Moonlight, set in Miami, Beale Street unfolds in a city neither had an intimate knowledge of—New York.

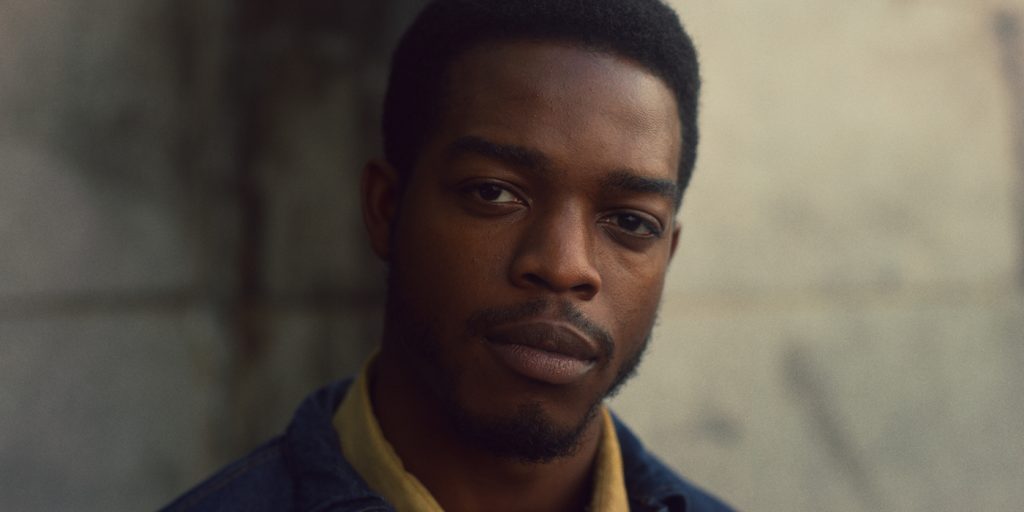

Set in 1970s Harlem, If Beale Street Could Talk provided Laxton and Jenkins the opportunity—and challenge—of depicting the lives of Tish (brilliant newcomer Kiki Layne), the fiancée of Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt (played by Stephen James) in a city they’d need to get to know, fast. Tish becomes pregnant, and as the two begin to plot their lives together, along with the loving support of Tish’s family, their lives are upended when Fonny is arrested for a crime he didn’t commit. A race against time begins as Tish, her family and Fonny’s father try to prove his innocence before the baby is born.

“Moonlight was shot in Miami, Barry’s home town, and Medicine for Melancholy was shot in San Francisco, which I knew well,” Laxton says. “This is the first film Barry and I made that wasn’t set in a city or place we were very familiar with, so both of us had some deep concerns about making sure we were depicting New York and filming it appropriately. Place is such a huge thing for Barry and me, we make so many visual approaches based on our surroundings. I have such a hard time visualizing a movie until I’ve spent time in a place. When we did Moonlight, I didn’t even take my camera around to scout for 2-3 weeks, I wanted to let the place soak into me. I did the same thing here. Lucky for us we had an amazing production designer in Mark Friedberg, who is a New Yorker, and he was alive during the 70s and sort of knew the story in a much more intimate way than Barry and I. Another thing about New York is there are places that haven’t been overly developed since the 70s.”

Laxton and Jenkins didn’t want the film to look like it was shot in the 70s, but rather, that we were seeing the film the era through a modern prism.

“I was more involved with trying to find a way to choose the right lenses and create a visual language that more broadly hinted at the 70s,” Laxton says. “While we hinted at some vintage qualities, it’s not the New York hand-held documentary approach, like a Cassavetes film. We wanted to make it very different kind of film, with a different language, and find a way to blend that decade without it feeling dated because the story is so topical.”

One location that gave Laxton everything he hoped for was a bar where Tish and Fonny’s fathers, played by Colman Domingo and Michael Beach respectively, plot what they’re doing to do to help pay for legal counsel to spring Fonny from prison.

“That was a bar in Harlem called Showmans, and that location, like so many others, were gems,” Laxton says. “Our team for a lot of locations that hadn’t really been touched since the seventies. This bar, in particular, is such a wonderful example of that. New York is a fabulous city with such a deep, deep history. If you’re paying attention, you can find these places and pockets that have found ways to hold onto their roots.”

Anytime you adapt a novel for the screen, you’re wrestling with what to leave out. When you’re adapting a novel from a legendary, iconic writer like Baldwin, this process is all the more delicate.

“I think we usually talk about adapting novels from a screenplay point of view, or the art department can look at the novel for more detailed indications of what the spaces look like,” Laxton says. “For us, it was a way we could think about the visual language. When I think of James Baldwin’s writing, I think of his detail, his specificity, his nuance, and his moral clarity. When thinking about how to move the camera, what lenses to use, what format to choose, it was about finding ways to bring Baldwin’s voice and approach into the visual choices we made from a camera and lighting perspective.”

One example of this is the film’s format. Laxton chose the Alexa 65, which has a field of view that’s much larger than most 35mm cameras.

“This camera has more resolution, and that spoke to me about the specificity and detail that Baldwin has in his writing,” Laxton says. “That field of view has great power I felt, great strength, which is also in his writing.”

Laxton also spent a lot of time thinking about Beale Streets themes.

“I think the movie is about a lot of different things; race relations, being black in America, the prison system, but it’s also about love,” He says. “If we found a way to see this film, this story, through a prism of love, through the gaze of two young lovers, it would feed the conflict that surrounds their love. You can find ways to identify and engage with their emotional route if you saw it through their eyes, how they related to their families, and that’s the context we wanted to view the other issues through. Everyone understands family love, young love, no matter where you come from, black or white or Asian or Latino, we all have family and we all know what love feels like, hopefully. If we can experience things we understand as people, like love, that’s the context all other issues pass through.”

In one of the film’s most potent scenes, Brian Tyree Henry plays Fonny’s friend Daniel, recently released from prison. What begins as a casual conversation among friends who haven’t seen each other in a while becomes a moving, harrowing meditation on what prison does to a man, especially a black man, especially one who was innocent in the first place. It’s a haunting, beautifully rendered sequence made all the more powerful for how Laxton’s camera lingers on Daniel and Fonny’s faces.

“The question we had was how do we want to pan back and forth between those two men at the table,” Laxton says. “The patience and time we spent on them was rewarded by the editors, who didn’t cut too much, and who let that space provide such an intimate capsule where these two gentlemen could share deep and dark and vulnerable moments together. In doing so, with the way the light plays through the windows and how the camera moves between them, we created both brotherly bond between them, but also this deep, dark intensity as well.”

The more Daniel gets to talking about his experience in prison, the more vulnerable and shattered he reveals himself to be. Baldwin’s clarion-clear voice, so eloquent and so impassioned, comes through with the specificity and clarity with which Daniel describes being tortured by the white prison guards.

“For someone like me, these are conceptual, theoretical talking points,” Laxton says. “I may have a cursory conversation about prison reform at a dinner table with friends who look like myself, but in actual fact, these are much more real, tangible, intimate issues for people of color of this country, and they have a very different kind of conversation,” Laxton says. “That’s the context we wanted to portray.”

Once Tish returns home with the groceries, Daniel changes the subject, not wanting to spook her (although she’s strong enough and then some to take it) and to enjoy what he’d only dreamed of while in prison; a warm meal with friends. It’s a heartbreaking shift, one people like Daniel have long been forced to make.

“That break when they go from this extremely painful conversation to a casual dinner moment, that’s how people of color in this country have to approach things on a daily basis on some level,” Laxton says.

Some of the film’s most crucial scenes take place in the partitioned room where visitors can speak to inmates, separated by a thick wall of glass, via phones. This is where Tish and Fonny are forced to talk for much of the film.

“Going into the prison scenes, one thing was always on our mind was to make sure we were crafting visual choices in ways that gave Barry and the editor choices later,” Laxton says. “We wanted to give them options to make sure we can feel the distance between Tish and Fonny. One way we did that is sometimes we shot them in profile, and you felt like you were on one side of the glass or the other, and sometimes we removed the glass entirely. There are moments where they feel like they can reach across through the glass and hold each other, and then clearly there are moments where there’s this distance between them, and it’s such a tragedy.”

If Beale Street Could Talk pulls the viewer into the love Fonny and Tish have each other in a way that’s unusually intimate. Some of that intimacy is generated by Jenkins and Laxton’s choice of having the performers look directly at the camera, giving the viewer the sense they’re the ones being looked at with love.

“Barry and I, being who we are, like having the performers looking at the camera because for us it says something more broadly what experiences we can hope to have watching a film,” Laxton says. “Through those shots of our characters looking directly into the lens, we’re asking the audience how would you really feel if you were in this character’s position in a very serious and intense way. That’s the question one hopes people ask when they leave theater; we’ve all been in love like this once in our lives, especially as young people, only I didn’t have to ask the questions that Tish and Fonny are asking each other at that age, yet here they are at that age having to do so. That technique of having them look into the camera is a little about that; we’re asking our audience to put themselves them into the character’s positions.”

Featured image: KiKi Layne as Tish and Stephan James as Fonny star in Barry Jenkins’ IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK, an Annapurna Pictures release. Photo by Tatum Mangus / Annapurna Pictures