Garrett Brown: An Interview With a Visionary—Part II

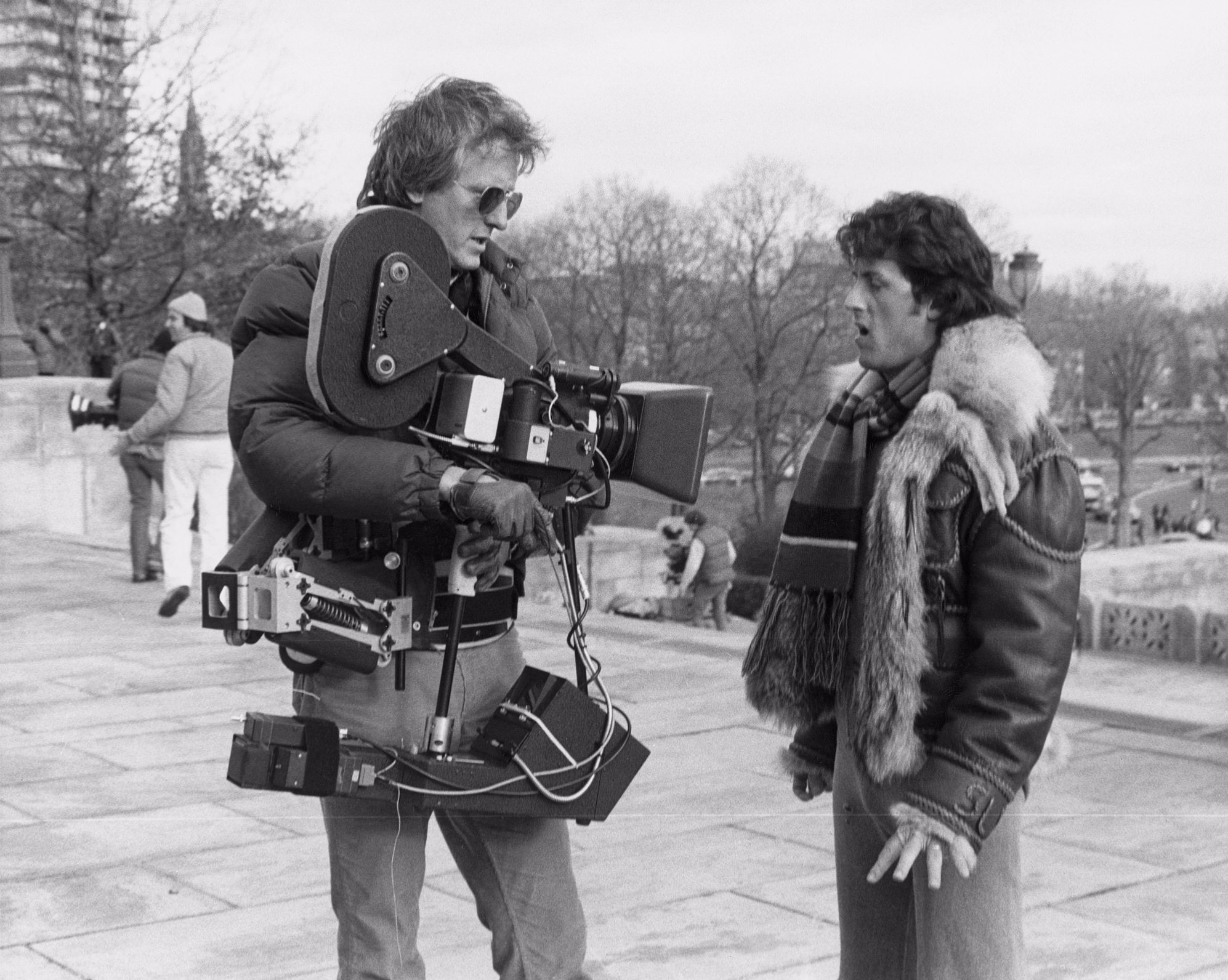

In part one of our two-part conversation with Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown, the Philadelphia-based cinematographer talked about holing up in a motel for a week in the early 1970s to experiment with designs for a more commercial version of his revolutionary camera stabilizer. He talked about shooting his first-ever feature film using a Steadicam on Bound for Glory. And he described his improvised solution for filming one of the most famous scenes in all of cinema history: Sylvester Stallone running up the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum in Rocky.

In part two, Brown takes us behind-the-scenes with director Stanley Kubrick while shooting The Shining, describes his favorite scene from more than four-and-a-half decades of work in the industry, and speculates about the future of Steadicam.

You worked on Reds with director Warren Beatty. A photo from the shoot on your website features the caption: “on the camera car with [cinematographer] Vittorio Storaro before being humbled by Spanish potholes.” What happened?

We were shooting in Almeria, Spain, as a stand-in for Baku, and our camera car had to keep pace with a steam train dressed with Soviet flags as it pulled into view. Vittorio offered to fill in some of the obvious potholes in our path. I said, “Not necessary, it’s the Steadicam!” Well, Warren was riding along, looking at the monitor, and at the end of the rehearsal, he turned to me and coldly said, “Garrett, that wasn’t very good.” It was the greatest chill of my young career, and I squeaked, "I know Warren, I’ll fix it! Don’t worry!” So of course I took Vittorio’s offer to have the potholes filled in, plus some giant windscreens, and we finally got the shot.

Let’s talk about Kubrick and the scenes in The Shining with the little boy, Danny, zipping around the empty hallways of the Overlook Hotel on a Big Wheel. How did you set that up?

Knowing that Stanley liked multiple takes, and that Danny seemed tireless, it was clear that I could not run along with him and do more than a take or two without being completely 'knackered' as the Brits put it. So I auditioned every possible vehicle that I might ride on including a dolly and even a skateboard. The winning contraption, although imperfect, was a custom wheelchair that Ron Ford had designed years ago, with input from Stanley, for handheld shooting. It came with a crude seat, which I positioned very low, and hard-mounted the [Steadicam] arm with a bracket I had made at the studio machine shop.

So you didn’t have to wear the Steadicam apparatus itself?

No. In fact that was the origin of so-called 'low mode', with the camera mounted underneath, a mere inch above the ground. Our poor grip Dennis (Winkle) Lewis pushed the chair and we skimmed along at the fastest speed he could maintain. Fortunately, I had the microphone mounted on my camera, because no one anticipated how amazing the sound of the Big Wheel running alternately over the bare floor and carpet would be. Unfortunately we could only use the audio from that very first take, as Winkle began huffing and puffing so loudly, and saying things like, “F— me, Stanley, I can’t do it, the kid’s tireless!” and subsequent tracks were mostly unusable.

How many takes did you do?

At least thirty, each several minutes long. And true enough Danny was completely tireless. Apparently there is some kind of perpetual motion unknown to science going on with a Big Wheel; a kid can ride one of those things forever. But when we heard the dailies, with that incredible sound of floor and carpet, it became the main attraction for that shot—and of course we all immediately took credit for the idea.

The exteriors of The Shining featured a lot of snow. What was it like working in those conditions?

They used so-called ‘dairy salt' as a stand in for snow—900 tons of it. Unfortunately rain turned it blue so it constantly had to be covered up with new salt, and little fragments of Styrofoam, shaken out of giant hoppers overhead on cranes, stood in for falling snow. And then there was smoke—oil smoke in that era—to make things look misty and cold and wintry. We trudged through salt in the labyrinth on days that sometimes reached 100 degrees. But deep blue color timing made it all look startlingly real, except for the breath of the actors, which Stanley agonized over, but we didn’t have a choice.

Today much of that set, and the actors’ breath, might have been created digitally.

That’s true. Many of the sets that I worked on will never be built again because it no longer makes sense financially. And that’s too bad because those great old sets were grounded and real and at least obeyed the laws of physics, unlike the occasional carelessness of low-end CGI. The rope bridge in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom was actually 380 feet in the air with large gaps between the boards, yet navigable! A digital remake would have absurdly huge gaps and be 1,000 feet or 10,000 feet in the air! Why not? It takes just a keystroke—but somehow it isn’t as viscerally impressive to viewers. It becomes a cartoon. I feel lucky to have to have worked in the era when we actually built stuff and shot it! On the other hand, Spielberg got it right in Jurassic Park with the Tyrannosaurus Rex, particularly that shot of the surface of the liquid in that glass vibrating as the T-Rex is getting closer.

Turning back to your career, what do you consider the highlight?

The sequence that gave me the most satisfaction was in 2000 when I got to work again with Vittorio Storaro on the opera La Traviata in Paris. It was live TV but had the quality of a movie. I shot three of the four acts, concluding with a 23-minute nonstop sequence as Alfredo arrives and Violetta finally expires at a window in a little apartment on the Île Saint Louis overlooking Notre Dame. The cathedral was lit by Vittorio and the bells went off at midnight just as Violetta dies. It was astonishingly intimate and emotional. Although I am not a big advocate of non-stop shots, this one made sense to me. The emotional quality of it just kept building, in part because it was uncut. It was beautiful.

The Steadicam looks relatively easy to use. Do you think that’s a misperception?

It’s an invention that doesn't work by itself—it's an instrument. And when you finally learn to play it really well and, in essence, make visual music, you get at the aspects of camera operating that I love, and that are so important to the success of a movie. One's emotional connection to the material has a lot to do with the way the operator moves and accelerates and decelerates our viewer’s eye. So it’s not exactly easy—not because its physically so challenging, but because it is an instrument, and you have to, in effect, read the score six bars ahead to perform effectively in the moment.

Finally, you not only invented the Steadicam, but the Skycam that we see zipping over stadiums during sports events, and the Divecam and Swimcam that we see primarily at the Summer Olympics. What’s next from the mind of Garrett Brown?

That’s a secret!