Painting a Renaissance Masterpiece From Scratch for The Grand Budapest Hotel

Renaissance painter Johannes van Hoytl the Younger (1613-1669) worked in solitude. Known for his use of light and shade, as well as his attraction to the lustrous and velvety, the painter was particularly un-prolific and a financial failure. Yet, van Hoytl nevertheless produced up to a dozen of the finest portraits the world has ever seen.

He also never existed.

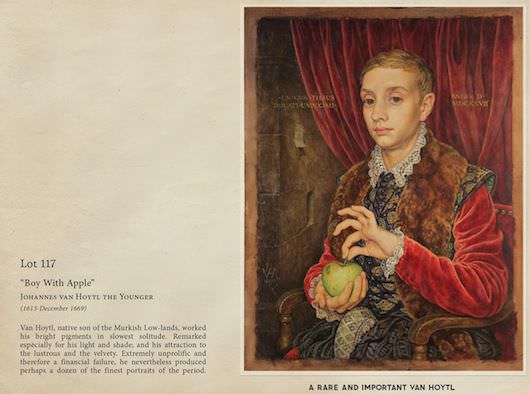

In 2012, director Wes Anderson approached 62-year-old British portrait artist Michael Taylor with a unique challenge: create a fictional Renaissance painting—not too Italian and with a bit of a northern spin—for his upcoming film, The Grand Budapest Hotel. Willed to super-concierge Gustave H (Ralph Fiennes) after the death of his wealthiest (and oldest) paramour, Madame D (Tilda Swinton), van Hoytl’s “Boy With Apple” hangs proudly at the center of the caper that follows, as Gustave is framed for murder, steals the priceless painting, and eludes the goon squad hired by his lover’s greedy children.

An artist whose works have appeared in London’s National Portrait Gallery and Parliament’s House of Lords collection, Michael Taylor had never worked on a motion picture before. And to this day he has know idea how the besuited auteur found him. “Wes just called me up,” Taylor explains. “This was completely new ground for me—and there ended up being a pretty steep learning curve.”

The work began when Anderson gave Taylor the film’s script and a stack of reference images. “He sent me all kinds of stuff for inspiration, from old postcards of Bohemian castles and handed-tinted photos of grand hotels to even some pictures of fancy cakes,” Taylor remembers. “Among the paintings there was an Albrecht Dürer, a Hans Holbein and some other Tudor portraits along with Bronzinos and, as I remember, Lucas Cranach. Rather weirdly, he also included my own portrait of Lord Falconer!”

Though Anderson shared a few specific requests for “Boy With Apple,” such as incorporating a slip of paper nailed to the back wall (a touch inspired by Georg Pencz’s “Portrait of a Young Man”) and the use of actor/dancer Ed Munro as the model, the director gave the artist freedom to create his own portrait. “We bounced ideas and suggestions back and forth quite a bit at first,” Taylor explains, “but Wes left specifics very much to me.”

Take the way our subject toys with the apple stem. Taylor had always been fascinated by the fingers holding the nipple in “Gabrielle d’Estrées and One of Her Sisters” in the Louvre, so he decided to incorporate that.

The same goes for another inspiration: Bronzino’s portrait of Lodovico Capponi. “That cropped up several times as a reference,” says Taylor. “We were trying to create something parallel, something that never really existed but seemed like it might have. It had to have a familiar look but actually be an original.”

Unsurprisingly, Anderson was most opinionated when it came to the costuming. “Wes was very insistent that we had furs, and the cod piece was a must,” laughs Taylor. “There was also quite a bit of rummaging about in the dressing up box to get the costume right. In the end, we mixed up several costumes—the sleeve from one, the collar from another and so forth.”

Taylor spent the first few months working on his own in an appropriately Jacobean house near his Dorest home. Anderson asked to see the unfinished picture as filming neared, offering an initial round of critiques. The director’s first complaint: the painting looked too much like one of Taylor’s. (“I thought that quite funny coming from someone whose films are unmistakable from seeing one frame!” says the artist.) The pair found common ground through a lengthy email exchange, with Anderson giving his (apologetic) notes and both deciding to sacrifice some elements (a pewter plate with a bird skull, a picture of a castle, a curtain rail) in the name of simplicity. All told, it was a process that would have made the error-prone Old Masters proud. “Rather authentically, an X-ray would reveal several versions!” says Taylor.

From first sitting to delivery, the process took four months, including a break for Taylor to travel to Korea for his son’s wedding and few stops and starts after model Munro was cast in a West End production of “Singin’ in the Rain.” In the end, Taylor commends Anderson for what he calls the director’s “non-specific specificity,” an uncanny ability to get exactly what he wanted while remaining courteous and respectful of the process.

In a tasty slice of art imitating movie life, Taylor knows nothing about the current whereabouts of “Boy With Apple.” “One of the charms of making paintings is that you send this thing out into the world where it has to make its own way,” Taylor muses. “I constructed a nice padded box to protect it for the rough and tumble life on set with instructions on how to care for it pasted to the lid. That was the last I saw of it until I watched the film.”

As The Grand Budapest Hotel continues to resonate with audiences after its wide release, Taylor can take pride in the fact that the 400-year-old portrait he painted is a key to the film’s success. But creating an invaluable masterpiece hasn’t gone to his head. “I don’t think ego comes into it,” says the artist, “and I didn’t find it hard to put a price to the priceless!”

Featured Image: Gustave H. (Ralph Fiennes) showing off "Boy With Apple." Courtesy Fox Searchlight Pictures.