The Grand Budapest Hotel Production Designer Adam Stockhausen Goes Handmade

Seven years ago, a young art director was given an appropriately quirky assignment on the set of The Darjeeling Limited: design the dishes for the dining cabin of Wes Anderson’s India-traversing train. It took “an awful lot of versions” to win over the discerning director, but Adam Stockhausen must have made a good impression—since then, he has served as production designer on Anderson’s last two films, Moonrise Kingdom and The Grand Budapest Hotel. And whether his assignment was large (turning an abandoned east German department store into the epitome of 1930s grandeur) or small (designing an entire currency for the fictional Republic of Zubrowka), Stockhausen rose to the challenge. Fresh off an Oscar nomination for his work on 12 Years a Slave, he talks to The Credits about working with a director famous for his attention to detail.

Wes Anderson’s films had a set aesthetic by the time you did production design on Moonrise Kingdom. Did you have to take a crash course in his style to learn the ropes?

Wes has a definite vision coming in and is intimately involved in every choice we make, from scenery to costumes. But there’s no handbook to working with Wes. Each project is unique and we really start from the references, talking about how to make something from scratch.

What does that research phase involve? Were you literally just studying up on Eastern European hotels in the 1930s?

It’s stuff on the Internet, it’s archives from hotels, it’s books, it’s movie references, it’s all kinds of stuff. For instance, we looked at this collection of photochrom postcards from the period that are black and white and then hand-painted. They were a nice big picture way into this. But then we dove very quickly into specifics—and there was a mountain of specifics. It goes down to the tiniest detail, like the fobs attached to the hotel keys. We have a whole folder of reference images for those. We even custom designed a currency, the klubek. So it was a whole research process of just looking at difference currencies that we liked.

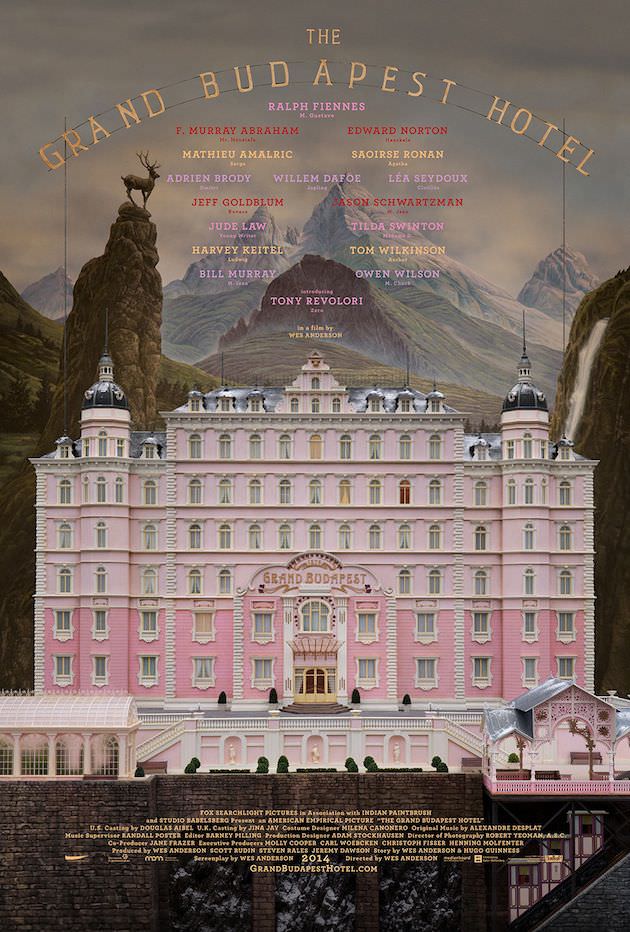

You built an actual 14 foot by 7 foot model of the Grand Budapest, the same one that made the movie poster. Why go the miniatures route?

With the hotel exterior, we knew early on that Wes wanted to present it in a very specific way with the hotel on a hillside reached by funicular train with the pastel-colored town below. That’s not something that exists, so we had to make it. You can go down the digital path, but the old-school technique of making a physical model is appropriate with the handmade quality of the film and the period that we’re referencing, because that’s how they would have done it in the thirties.

Why build it so big?

The trick with making models is you can only go so small before the detail becomes impossible. So to get the level of finish we wanted with all the mullions in the windows, for instance, there’s only so small you can get before you lose the cost advantage. Bizarrely, if it had been half that size it would have been harder to do.

So did Wes want you to take bits and pieces from real-world places? Would he go so far as to say, ‘take the windows from here and the concierge desk from there’?

Exactly. We take that in the real-life places where we go and scout. For instance, in the hallway outside of Madame D’s suite, the windows and general layout comes from a hotel in Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic, but then the doors come from a Bergman film called The Sound. So we take the bits that excited us from all those sources and just shake it up. Then you have to synthesize that so it doesn’t just look like a collage. That’s the tricky part.

But some locations did meet your standards. How did you transform a bankrupt department store in East Germany on the Polish border into the Grand Budapest?

The department store we took over in Görlitz, Germany had the basic structure we wanted and then we built into it. So take the shootout under the atrium. That’s the top floor of the store. The railing and big window were already there, but then we added the walls with all the rooms where everybody was ducking in and out.

You also shot the lobby in the department store, but where did you find your grand ballroom?

That’s also in Görlitz and it’s kind of a civic center. It was a big hall for concerts and speeches so there was a stage, but it’s been out of commission for a long time so the seats were all ripped out. Then we added the carpet and the mural you see at the end of the room, which is a stag on a rock that references the German painter Caspar David Friedrich.

There are also the bleak staff quarters of the Grand Budapest. What inspired those?

What Wes wanted there was the upstairs-downstairs quality to be pushed to an extreme level. That gives us a tremendous amount of range all the way up to Madame D’s suite. For instance, Gustave’s room is extremely small, and that was a little room in a little building we found right in the center of Görlitz.

Speaking of bleak, we also see the Grand Budapest after the war in a drab sixties style that’s almost like a reverse Mad Men. What was your inspiration for that?

Well, it was definitely brutalist architecture in general, but then there’s that look that’s specific to when buildings were redone in East Germany. No one is concerned with detail, so they take what had been the beautiful, hand-painted thing and slap a sign on it that says, ‘the toilet is right over there.’ We made that a feature of the place.

When all is said and done, do you have a favorite moment in the film from a production design standpoint?

The one I love is a shot where Bill Murray is taking Gustave and Zero to the train. Their car drives in under the bridge and out of the frame. Then it comes back from the other side, the train pulls up and the guys hop on. It was a complicated little shot because there wasn’t enough time to get the first car up and around, so we had to time two cars. And then we pushed in this piece of train that was low-relief, so it was about two feet wide and literally made from cardboard and beeswax. But somehow it all worked. I loved that shot.

You went from 12 Years a Slave straight to Grand Budapest Hotel. Was that as big a leap for you as it would appear to be from the outside looking in?

The process is very different because the way Wes shoots is very different from the way Steve McQueen shoots, but the skill set is the same. It’s still the same process of finding the truth in the historical research. And we’re still asking how are we going to execute this? What do we need to do to make this happen? Believe it or not, it’s the same job.

Featured image: Tony Revolori and Saoirse Ronan in The Grand Budapest Hotel. Courtesy Fox Searchlight Pictures