Dawn Porter on her Netflix Docuseries Bobby Kennedy for President

It’s been 50 years since the turbulence of 1968 changed this nation forever. From the escalating Vietnam War to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. to the riots outside the Democratic convention, that year was one of the most difficult our nation has ever faced, and that serves as measuring stick anytime a particular year in America feels especially fraught. Last year was one such year. So was 2016. The same could said of 2018. Yet do they reach the level of world-shaking events that were contained within 1968?

Consider that was also the year that New York Senator Robert Kennedy, brother of the late 35th President, campaigned to become the 37th President of the United States. That campaign ended in tragedy when Kennedy was murdered only two short months after the death of Martin Luther King Jr.

In her new Netflix documentary series Bobby Kennedy for President, director/executive producer Dawn Porter explores the life and legacy of RFK. From his work as the United States Attorney General to his tenure as a New York Senator who spoke out about poverty, the four-part series focuses its attention on the beloved Democrat.

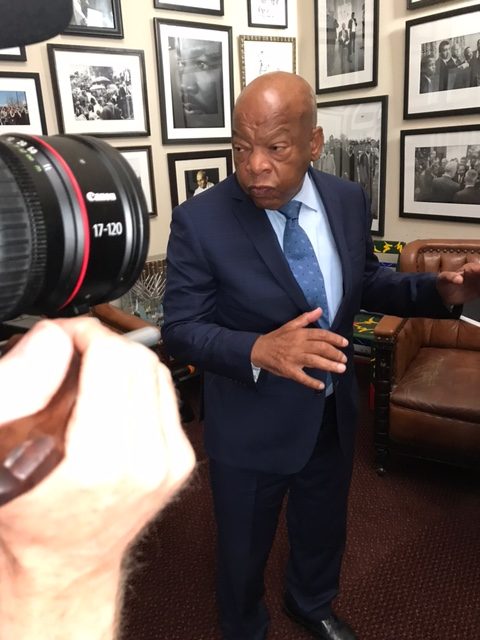

Porter explores Kennedy’s important work using archived footage of the presidential candidate and interviews with many of his associates, including Congressman John Lewis. In addition to interviewing known political allies, Porter also interviews other people whose lives were forever affected — directly or indirectly —by RFK. Juan Romero, the busboy who held up Kennedy’s head after he was fatally wounded, is featured prominently in one of the episodes here and so too is Munir Sirhan, whose brother Sirhan Sirhan was convicted of murdering Senator Kennedy.

I recently had the opportunity to talk to Porter about the challenges in locating her interview subjects, the appeal of RFK and how his legacy can serve as an inspiration today.

Below is a slightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Before you started work on this documentary, did you already know a lot about Robert Kennedy?

I would say I didn’t know enough. Obviously, [I knew] about his life, his assassination, his legacy. It wasn’t like I was a Robert Kennedy scholar or anything like that. I was approached by a German production company that I work with a lot and they had a particular angle and then we started talking and developing it and I just really felt like there’s so much to the Senator’s life. It was a good time to take a look back and reexamine that. The one thing I will say is that Robert Kennedy was always a really important figure in the African-American community because of his later work on civil rights and so that was really interesting and important to me. I wanted to explore the roots of that.

How did you decide what to focus on?

I felt like there’s a whole new generation of folks including my kids – I have teenagers; I have a fourteen and a fifteen year old – who would be interested in a politician who spoke truth to power [and] who was compassionate. I felt like I wanted to go back to the beginning enough to get an understanding of why he was so important and what he did that changed politics and change American culture. That was the first objective. The second thing was, ‘Well it’s a film, you gotta have either an eyewitness or footage to tell that story.’ We had great story producers. They did this exhaustive mini-book on Kennedy and then we matched that up with our archivist. There are just thousands of Bobby Kennedy stories and they’re all great and so like you say, you have to exercise some restraint, which was hard to do.

Can you talk more about the archivist and the process he went through to get the footage?

He is Rich Remsberg. He’s spectacular. He went to literally a hundred different sources. We ended up using 75 different sources in the project, so he went everywhere and looked over as much as he could, and then one of the big challenges was just getting it organized so that we could make sure that somebody was putting eyes on all the hours of footage that we collected. So figuring out that process was our first big challenge. Rich went to the big sources and a big source for us was news networks. They had just started covering Bobby Kennedy’s life and campaign in the 60s, so there was a rich source of footage and we got a lot that had not been seen before. And then the third source was independent filmmakers. There were all these people that would become legendary filmmakers like D. A. Pennebaker and Robert Drew, so we went to them — their families in the case of Drew and [Charles] Guggenheim and then to Pennebaker himself—so we did that exercise. There were some really wonderful moments from that effort.

How did you decide who you wanted to interview for the program?

The goal there was to really have people who closely worked with him, not people who were observers. We didn’t want to have just historians. I think that’s been done and that is done very well in many places. I was more interested in who were the people who were there, the people who were in the fight. They didn’t know what was gonna happen at the time. They just were living it and could they recall the experience of living it, so we went to very specific people and most of them, mercifully, were available.

Was it difficult to locate specific people like Juan Romero, the busboy who held up Kennedy’s head after he was shot, or Sirhan Sirhan’s brother Munir?

Juan Romero, who came to our screening, is now really speaking extensively for the first time. It took a little detective work to find him. He lives in Southern California but once we found him, he was eager to be re-united with a Kennedy aide Paul Schrade.

Sirhan’s brother Munir — who is just a lovely person — we got through conversations through Sirhan’s legal team. They were close with him. Once we talked about it and they understood what we wanted to do — we didn’t want something salacious or anything like that —they had us meet [Munir], get him comfortable and then he agreed to do filming with us.

There’s a scene in the story when Congressman John Lewis is talking about the death of MLK and RFK and he starts breaking down. Was it difficult to get people like him to open up emotionally about these tragic events?

It’s very fresh for all of them. It’s so important to tell those stories, particularly Congressman Lewis. He’s still so respectful. Obviously, I admire him for so many reasons. He is an icon. John Lewis is an icon himself and he is so respectful of working with Bobby Kennedy and that time of his life. He is a very, very busy person and gave us a lot of time. He’s an authoritative, moving, compelling voice and the film would not be the same without him in particular.

How do you explore Robert Kennedy without making him into a saint?

I think viewers are sophisticated. We understand that people are human. I think that makes us love them more. For them to be flawed. Also, you can’t understand how far he developed unless you understand where he started and if we just make people monuments— and not living, breathing creatures— it makes it seem like greatness is beyond us and that’s not true. I think one of Senator Kennedy’s greatest strengths was his ability to grow, learn and listen, and that’s something that anybody can aspire to. I’m not gonna be president of the United States but I can listen. I can welcome opposing sides. I can be more empathetic. Those are things that anybody can do so that was important for me to show.

USA. New York City. 1966. Portrait of Robert KENNEDY in his apartment.