How Blade Runner 2049’s Oscar-Nominated Sound Designer Pulled no Punches

As part of our Oscars week coverage, we’re re-posting our conversations with some of this year’s Oscar-nominees, as well as publishing new interviews with those vying for Oscar gold this Sunday. Sound editor Theo Green is nominated alongside his Blade Runner 2049 collaborator Mark Mangini. The Sound Editing category includes Julian Slater (Baby Driver), Richard King & Alex Gibson (Dunkirk), Nathan Robitaille & Nelson Ferreira (The Shape of Water), and Mathew Wood & Ren Klyce (Star Wars: The Last Jedi).

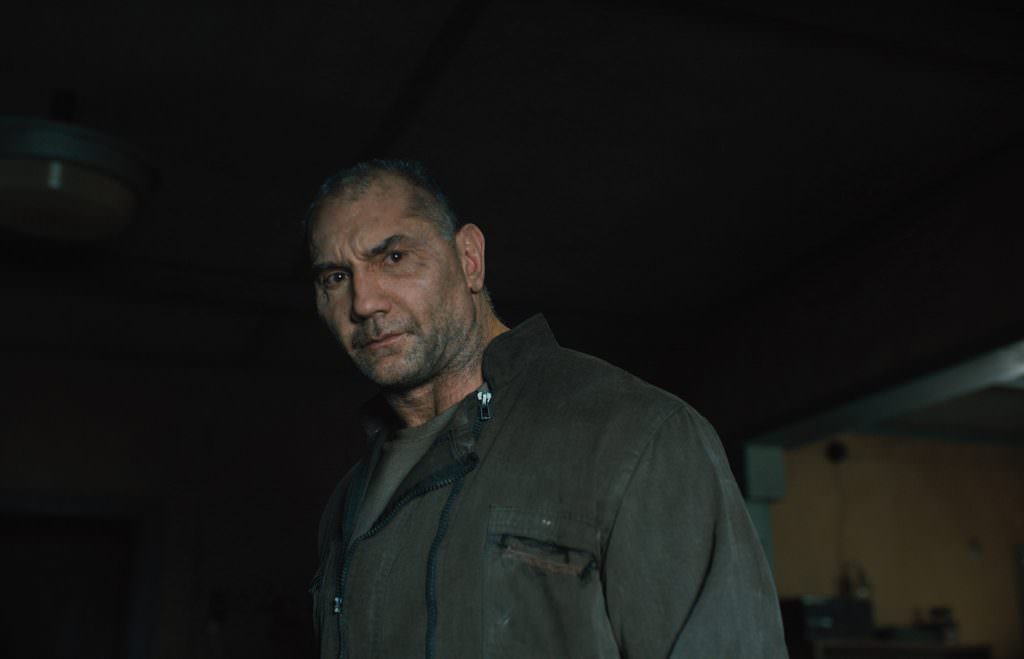

K. vs. Sapper

It’s a mismatch. One replicant is 6’0” and slender. The other is a goliath, standing at 6’3” and weighing 290lbs. They’re all alone in a creaky cabin on a distant, desolate protein farm, and they know they are about to have at it. The slender replicant, Officer K (Ryan Gosling), is there to “retire” Sapper (Dave Bautista, most well known as the lovable brute Drax in the Guardians of the Galaxy franchise), the rogue replicant whose existence is deemed an existential threat to the good people of Los Angeles, circa 2049. Retirement is, of course, a euphemism. K is seated in Sapper’s kitchen, the larger replicant standing above him, while a pot boils on a nearby stove. This is how Blade Runner 2049 begins, a scene of subtly building tension, shocking violence and minute detail that requires repeat viewing to take it all in. It’s a scene that sound designer Theo Green had been waiting to work on for years.

“Texturally, we’re seeing someone who’s been living off grid. We need to believe that Sapper has been self-sufficient on this little farm for some decades,” Green says. “He’s living in this shack, he’s got an old stove, old floorboards, old piano—relics of the old world. He hasn’t gotten anything technological in there, so all our sound work is really story driven stuff. He’s not really connected to the world K is a part of. So when we hear the floorboards creaking under his weight, that’s an important element. It sells just how badly matched they are, how under-powered K is compared to Sapper, who’s like a battle replicant.”

K’s got his gun on the table. Sapper asks him if he’d like something to eat. K tells him that he likes to keep an empty stomach before the hard work of the day is done. Meanwhile, the boiling pot on the stove does double duty in the scene, both placing Sapper in his relatively analogue world and signaling to the viewer, mostly subconsciously, that things are about to explode.

“The boiling pot sets up the underlying tension of the scene, and it leads to this mismatched fight that occurs,” Green says.

The pot comes to a boil.

“K’s half the size of Sapper, and he gets smashed right through the wall.” The sound of the melee is brutal, with Sapper’s every step causing the floorboards to groan, and his manhandling of K is thrillingly visceral. The hard thud of fist on flesh, the smash and crack of Sapper pounding K. into the living room floor. While we’re watching this initially lopsided fight, we’re hearing the sounds of a life being crushed. Yet K never panics. Even on his back with Sapper throttling him, the floorboards shaking, K.’s calmly waiting for his moment.

“I love the fact that it’s as if K has previous knowledge of what Sapper’s weak points are, and so he goes for the throat, and just like that, Sapper can’t breath,” Green says. The sounds are suddenly muted—Sapper grabs his throat, unable to breath. K. rolls over and finally gets to his feat. “We had to sell the idea that K, as a Blade Runner, has some background info on what a particular model of replicant’s weakness is, in this case he knows to go for the throat.”

As riveting as their fight is, Green and the sound team including Supervising Sound Editor, Mark Mangini, make great use of silence, too. They allow the viewer a measure of calm, a pocket of quiet, to assess what they’ve just seen. Something strikes you—Sapper is no monster.

“We set up Sapper as monstrously strong, but we didn’t want him to come across as merely a dangerous, violent monster,” Green says. “In many senses we wanted what K hears Sapper say in this moment to come back to him later, which it does when he’s flying through the neon canyons in Los Angeles. This is when the audience hears that flashback of Sapper’s voice saying, after he’s been beaten but before he’s been killed, ‘You’ve never seen a miracle.’ We realize in this moment that Sapper was part of the replicant uprising, and we develop our sympathies for him. We use sound to help set up how strong and dangerous a replicant can be, but also how sensitive.”

The original Blade Runner didn’t just change the way we looked at sci-fi films, it changed the way we heard them, too. Greek musician and composer Vangelis created the now iconic score for Ridley Scott’s neo-noir classic, which was nominated in 1983 for a BAFTA and Golden Globe for best original score. Using contemporary electronic instruments, Vangelis scored Blade Runner at his own studio, improvising the atmospheric sounds of a futuristic neo-noir Los Angeles while watching videotapes of scenes from the films, in effect creating an almost live score of Scott’s film. The results literally speak for themselves.

Yet Vangelis didn’t just score Blade Runner, he also contributed to the sound design, augmenting his lush, foreboding atmospherics with brilliant foley techniques. Not only did Vangelis capture the sense of levitation when a Spinner car lifted off with his music, he also imbued the sets and props with subtle sonic signatures. For example, when the polarizing windows in Tyrell’s office reduce the amount of daylight pouring in, Vangelis created a specific, whirring sound provided by ‘musical drones’ that were integrated into the score.

Green already knew all of this. The British-born composer and sound designer was not only a huge fan of Vangelis and the original Blade Runner’s score, he was also something of a student of the iconic composer. Years earlier, Green learned about the incredibly subtle, intricate sounds Vangelis created to color Blade Runner by obsessively listening to the bootleg “Los Angeles, November 2019.”

“I’m enough of a geek that maybe fifteen years ago, when I got my hands on a copy of ‘Los Angeles, 2019,’ I realized it was way more than just Vangelis’s score. It was extracted from the soundtrack of the film itself, so it included sequences like Deckard’s apartment, or the police station, or Chinatown, and these were atmospherics and sound ambiences that had been created for the film.”

This was sound design meant to slip, unnoticed, into the viewer’s subconscious, work that not even the most astute Blade Runner fan could identify. It turned out the world of the original Blade Runner was much deeper than most people realized, yet as a sound designer, Green was particularly primed to appreciate just how brilliant Vangelis’s work had been.

“For one track, its pure rain with wind chimes in the background. That’s it. Another track was a passing spinner craft in the night. It’s just such a richly atmospheric, ambient album. So I dug into Vangelis’s work and put together the constituent parts of the album,” Green says. “I’d say about fifty percent of it was him just experimenting with sound textures, while another half was the work of the sound designer Jim Shields, with additional sounds from Ben Burtt, the famous sound designer of Star Wars [the man who created, among other iconic sounds, the purr and whoosh of a lightsaber].”

When you watch a film, what you see is limited to the size of your screen. When you listen to a film, however, the sound escapes those borders and fills your entire world. This is certainly what director Denis Villeneuve wanted when he was auditioning composers. Green got his shot—a six-week trial on set in Budapest.

“Joe Walker [Blade Runner 2049’s editor] and I compared notes, as we both realized we had listened extensively to ‘Los Angeles, 2019’ and we really geeked out to it,” Green says. “What an inspiration to be able to move past just the original score and listen to a piece of sound design instead. It takes you back into that moment when you saw first saw the film. That kind of notable sound signature that every scene has in the original, it really stayed with me. I’d been obsessing about it for years.”

Villeneuve was quick to learn that Green was his guy, and the six-week trial turned into 3-months on set. This is a highly unusual arrangement; most sound designers don’t work with the directors during the shoot, but for a film as lovingly obsessed over as 2049, it made sense.

“When the job came, one part of me was slightly unnerved,” Green says. “I had a sense of great responsibility and caution with the fact that we’re following up a film with such a strong visual and sonic identity. Denis had taken some visual liberties, but to counter balance those liberties, he felt it was important that the sound and music return us to that universe. And this was born from obsession. We all believed that there was something special in creating this extremely textured, layered, identifiable sound design.”

Green followed his work on set with another 9 months in L.A. designing the sound with Mangini and the team at the Formosa Group. Green brought everything he had learned over his career, and his close study of Vangelis’s work in the original, to bear on 2049’s sound, which included lush electronic music, foley techniques, and, crucially, silence.

K vs. Deckard

K’s central mission in 2049 is to track down the infamous Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a former Blade Runner who went from hunter to the hunted by the end of the original film. K. eventually locates him in an eerily empty, utterly dystopian Las Vegas, one saturated by radiation and devoid of all life. Save Deckard, and his dog. K finds him living in an abandoned casino, with a lifetime supply of whiskey and a very low tolerance for visitors.

K.’s arrival quickly devolves into a manhunt, where K.’s the prey—Deckard chases him through the casino, which he’s booby-trapped, and eventually they find their way into a theater. What follows next is a masterpiece of sound design, where what you don’t hear is as important as what you do. As K. scrambles through the dark with Deckard in pursuit, a hologram of Elvis Presley appears on stage. It’s a gorgeous shot, and had that been the backdrop of this part of the chase it would have been enough, but we’re in a post-apocalyptic Vegas where nothing works as it should. Soon enough, the hologram glitches out, appearing and reappearing in different locations. The same thing happens with a holographic Marilyn Monroe and a Bollywood dance number—they come alive, only to disintegrate moments later, and then pop up again somewhere else. The holograms randomness increases the tension and confusion, making it more likely that Deckard will get to K.

This is far from the scene that had been originally conceived, and exists in this thrilling form thanks in large part to Green and editor Joe Walker’s collaboration, saving the holograms from the cutting room floor.

“The Vegas scene had the most back and forth, the most iterations, the most planning,” Green says. “When I first saw it, it looked a little bit like a computer game, like someone built what it looked like very roughly, and we were planning where the music would go.”

The way the scene was original scripted, Deckard hunts K in this ballroom, and once inside they trigger the Elvis hologram. Elvis was supposed to give way to Marilyn Monroe, who would perform her legendary “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” number. The two would be fighting by this point, and then you’d have an entire Bollywood production going on around them. The idea was that Deckard and K would have to find each other amidst all of this holographic commotion. The scene was envisioned to be like a kind of musical dystopia, with one Blade Runner trying to kill another. A brilliant idea. So this was what they shot.

“The scene was shot in separate passes, so the VFX team could composite Elvis, Marilyn and the Bollywood number. After the first cut of the entire film, Denis was happy save for one scene—this ballroom fight. Denis felt like it didn’t belong in the Blade Runner universe. Instead it felt like we were going into a song and dance movie, and it didn’t feel tense enough. This is a manhunt, and we have to get across the fact that Deckard’s scared for his life— the last time he encountered a replicant he was in mortal danger.”

One of the issues was there was too much going on visually. Deckard and K were getting lost amongst the holographic performers.

“It became visually and sonically confusing, and tonally a break from the film.”

Villeneuve’s first idea was simply to strip out all of the music completely and see what the hunt looked like on its own. Yet Green felt like there was another way to include the holograms, but to strip them down and make them more of a piece with the rest of the Blade Runner 2049 world, which is a mixture of the technological and environmentally devastated.

“I started to focus on what the sounds could be in an empty room. So we stripped it down just the sounds of Deckard and K’s breathing and footsteps. Then Joe [Walker] and I figured out we could use little bursts of those holographic performances. We imagined the hologram projector that was creating Elvis, Marilyn and the Bollywood production was old and broken down, and the speakers are cutting in and out,” Green says. “So we developed the idea that actually the little bursts of Elvis could be glitching out, adding randomness and unpredictably to the scene. You never know where someone is going to appear. Once we did that, it suddenly started to feel like the manhunt aspect came back, because everything was unpredictable and therefore so much more tense.”

When you re-watch the scene, you’ll notice how beautifully tense the sound makes you feel. K comes into the room, Deckard chasing behind him, and Elvis bursts out of nowhere in a glitchy, three second performance. If you listen closely, you’ll hear another clever element—the sound of the projectors whirring overhead that Green added.

“You hear this machinery in the ceiling, which I created to make give you a better sense of what’s going on, first you hear the sounds of the hologram itself, then I imagined the ceiling is filled with all these tiny little projectors and they’re all breaking down. It’s like when we first see Joi and she’s tethered to a machine in the ceiling to K’s apartment, I imagined there might be some sort of old school hologram on an arm, so there’s sounds of something moving, and you occasionally see K looking up, which disorients him, and then suddenly BAM, he’s got a gun shot right next to his ear, then Elvis is glitching out again. We needed the musical performances to be surprising, unexpected, and Deckard is using them to his advantage to advance towards K. Suddenly it didn’t have that song and dance number anymore, it was tense and scary.”

We’ll be publishing the second part of our chat with Green later today. For now, you can listen to some of the sounds he created for Blade Runner 2049 below.

Featured image: (L-R) DAVE BAUTISTA as Sapper Morton and RYAN GOSLING as K in Alcon Entertainment’s action thriller “BLADE RUNNER 2049,” a Warner Bros. Pictures and Sony Pictures Entertainment release, domestic distribution by Warner Bros. Pictures and international distribution by Sony Pictures. Photo by Steven Vaughn.