Let’s Not Turn Back the Clock on Internet Video

As the Internet has done with many aspects of our culture and economy, it is liberating audiences and content creators from the constraints of the old, brick-and-mortar world. Critics say the movie and television industry was slow to embrace the Internet. But ironically, now that online video is ubiquitous, some of these same critics are trying to reverse time and drag the creative community—along with audiences—back into the pre-Internet era.

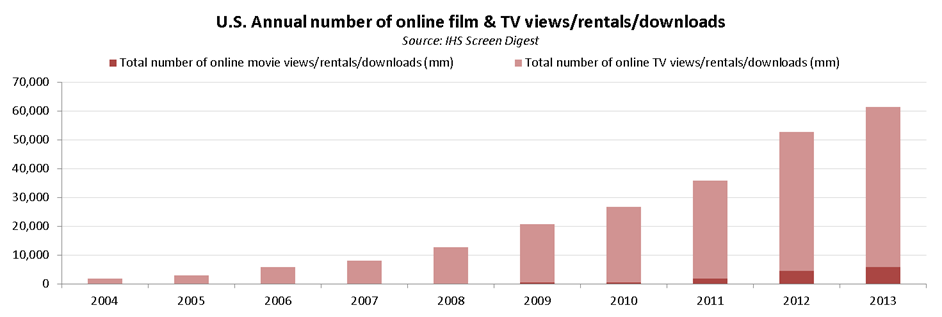

Immersing yourself in a story, a song, or a movie on your own schedule once required you to obtain an object: a hardcover or paperback book; a record or CD; a DVD or Blu-ray disc. Today, movie and television fans enjoy a variety of additional choices over the web. And those choices continue to grow. In 2009, more than 50 legitimate online services in the United States were already providing access to movies and television shows, and U.S. consumers accessed 376 million and 20 billion of them, respectively, that year. By 2013, the number of legitimate services had jumped to more than a hundred and U.S. consumers accessed 5.7 billion movies and 56 billion TV shows. You can see the remarkable 10-year uptick in Internet video consumption in the chart below. Yet apparently this isn’t good enough for some.

The current debate, highlighted in a Congressional hearing today, centers around whether Congress should intervene in this burgeoning and innovative Internet marketplace to impose a new government mandate that some call a “digital first sale” doctrine—a new rule that would significantly undermine these new and emerging business models.

The actual first sale doctrine, established by the Supreme Court in 1908 and codified the following year, is a limited exception to the copyright owner’s exclusive right to authorize distribution of his or her work. The doctrine says it’s not copyright infringement for owners of physical objects that contain copyrighted material to resell or otherwise dispose of those objects. It’s what enables you to resell books, DVDs, and CDs to a second-hand store. The doctrine’s effects on copyright owners’ rights are limited by the qualities inherent in physical objects: they take up space, require at least some effort to transport, impose costs to produce additional units, are often manufactured in limited quantities or otherwise become scarce over time, and decay with age. The U.S. Copyright Office has noted that the limitation of the doctrine to physical objects is not a relic of outdated technology but “a defining element of the doctrine and critical to its rationale.”

Technology now makes it possible to provide consumers new options by distributing content in non-physical form over the Internet, such as through download, streaming, and online subscription services. These license-based services are designed around flexible access to content, not the acquisition of physical objects, with prices varying depending upon the scope and duration of the access. Some of those choices are affiliated with UltraViolet, Disney Movies Anywhere, iTunes, Netflix, Hulu, Google Play, Amazon.com, and other cloud-based services. They enable consumers to watch programming anytime, anywhere, across multiple devices, and to share within a household.

Unlike with the physical ownership model, you don’t need to plan in advance, take all the content you might want to watch with you when you travel, or worry about forgetting to bring it. Moreover, if you lose or break physical copies of content you own, you will need to pay to replace them. You can’t lose or break Internet content, and if you lose or break your device, many services will reload the content for free.

Internet video also takes up relatively no space, is easily retransmitted and theoretically never decays. And if you know you are going to watch the content only once, you can often rent it as a stream or temporary download, thereby avoiding some of the cost up front, rather than buy the physical book, CD, or DVD, hoping to resell it later to recoup some of your investment and clear space on your bookshelf.

These services create flexibility for consumers that overcome the inherent limitations in physical objects, making creation of a new first sale doctrine for the online world unnecessary or at best of limited utility compared to the added benefits consumers enjoy from these digital services

More troubling, a new government mandate requiring creators to allow reselling of licensed Internet content would undermine incentives to create, reduce consumer choices, and deter innovation. Because of the inherent limitations of physical objects, the market for used goods is often distinct from the market for the goods when new. Sometimes the used good is cheaper because worn; other times it is more expensive because rare. Used physical copies of content therefore often serve as imperfect substitutes for new copies of a work. “Used” Internet content, by contrast, is indistinguishable from the original. It would serve as a complete substitute, supplanting the market for the originals and depriving creators of a fair return on their investment. Forcing creators to allow resale of Internet content they license would either require creators to substantially raise prices or discourage them from offering flexible, Internet-based models in the first place.

Licensed Internet content simply provides consumers more options, supported by a well-established foundation of copyright and contract law. The industry is moving toward the licensed Internet model because consumers are demanding on-line flexibility, and licensing is the best way to meet that demand. Those who prefer the physical ownership model still have the option to buy books, CDs, and DVDs. The fact that consumers are flocking to the licensed models indicates those models meet many people’s needs and preferences. If for whatever reason they don’t, consumers will turn back to the physical ownership model, and the content community will need to keep refining the license-based models or move on.

This is a relatively new marketplace. Government intervention now, seeking to force the content community to return to a 1908 construct built around physical ownership, will only short-circuit the experimentation and innovation that is going on all around us. The many options for viewing content today is solid proof that the best way to encourage choice and competition is to allow creators and distributors to innovate through new technologies and business models, rather than create expansive new exceptions to copyright.