Artist & Populist Both: HBO’s Spielberg Goes Deep on a Living Hollywood Legend

Is Steven Spielberg a populist or an artist? Like his exemplar, the iconic director Alfred Hitchcock, critics have often pointed to Spielberg’s fame to detract from or overlook his artistic accomplishments. At what many consider the height of Spielberg’s career in the 1970s and 80s, the director was one of the best-known filmmakers in the world, as well as one of the highest-grossing, with movies like Jaws, E.T., and Raiders of the Lost Ark smashing box office records. And yet, a move from such popular fodder to darker fare like Schindler’s List and The Color Purple, offered Academy recognition without the expense of losing his audience. Director Susan Lacy’s Spielberg, a new documentary premiering on HBO on October 7th, seeks to obliquely answer that question — populist or artist? — through highly personal interviews with the director and his family, as well as effusive reflections from scores of actors and Spielberg’s Hollywood peers.

As a primary source for much of Lacy’s more investigative material, the normally private Spielberg himself is candid and modest, discussing his childhood, Judaism, the trepidation he feels every time he shoots a new scene. In an interview with Dustin Hoffman, the actor appraises his director from 1991’s Hook: “Steven’s like a guy who works for Steven Spielberg.” Most of the actor interviews, which include Drew Barrymore (E.T.), Leonardo DiCaprio (Catch Me If You Can), and Oprah (The Color Purple) offer typically high but informed praise — “I can’t tell you how many people I interviewed who, ten minutes in, said ‘oh you’re making a serious film,’” Lacy says of her probing — and thanks to Lacy’s pursuit of reflections beyond sound bites, Spielberg is a pleasant, in-depth meditation on the director’s cultural influence and the wellspring from whence it came.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSdSYmXCPXU

Susan Lacy. Courtesy HBO.

The gray-haired cadre of male directors — Martin Scorsese, Brian de Palma, and George Lucas — once the “movie brats” who sought to change Hollywood together and are now its standard-bearers, also rhapsodize on the director’s accomplishments, but interspersed with a charming array of days-gone-by anecdotes. One might be tickled to learn, for example, that Star Wars’ iconic prologue was born from a recommendation made over dinner at a Chinese restaurant, from de Palma to Lucas, to better frame the characters’ backstory. To that end, film buffs of this era in particular will likely separately enjoy the documentary’s natural wealth of vintage footage, a late 70s and early 80s microcosm of flared jeans, beards, and aviators as normal glasses.

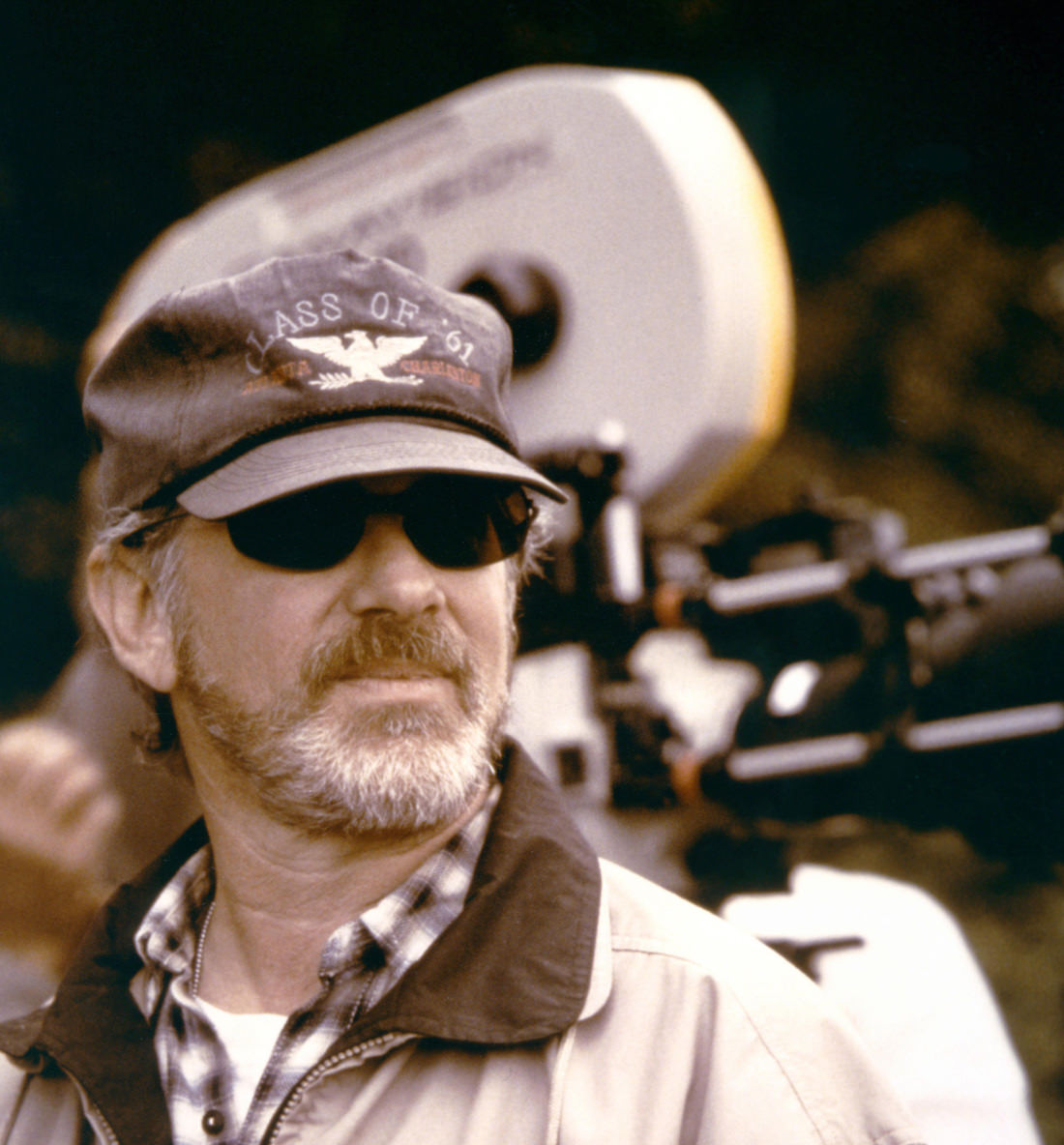

Steven Spielberg. Courtesy HBO.

As it pertains to Spielberg’s career, however, the documentary could also be called Spielberg, Director, 1961-2015. The movie offers a close read of Spielberg’s greatest hits as they relate to an usually intimate look at the historically private director’s autobiography. It hardly mentions his career as a producer (you’ll find no answers for Transformers 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 here), and stops short of discussing more recent work like The Terminal or The Adventures of Tintin. That said, at an amply-filled two-and-half-hours, Lacy’s “through line” for refusing to squeeze her thoughtful examinations of Spielberg’s most iconic works, in order to fit in, say, a meditation on The BFG, is understandable. “I wanted to delve into his work as a director, not as a producer, empire builder, or nurturer of talent,” she explains. “That would have been a ten part series.” Thanks to her tight focus, what emerges is a very clear picture of how aspects of Spielberg’s early life have become a foundation for almost all his work.

Spielberg’s audiences are accustomed to films that reflect one of two themes: a fundamental separation followed by cathartic reunion, or escaping bullies. These are both directly related to his own formative experiences growing up in the Arizona suburbs and Northern California. Interviews with his three sisters establish Steven as a restrained, imaginative child with his peers (even if he apparently enjoyed finding theatrical ways at home to terrify his siblings), who subsequently was picked on. Spielberg connects that experience with many of his films, even his directorial debut Duel, from 1971, in which a mostly unseen tanker driver stalks a terrified driver, for apparently no reason whatsoever. It is also Spielberg’s family who offer insight into the other theme to which the director has returned again and again. While it has been reported before that the Spielberg had a fraught relationship for a number of years with his father Arnold, the underlying reason (Arnold actually protected his wife, Leah, who left him for his best friend) remained mostly private. However, as one of Spielberg’s sisters points out, the director wanted a “Father Knows Best” kind of family — and this plays out in the Spielbergian themes of separation and reunion, as well as revealing itself in a well-known affinity for the master of quaint Americana, Norman Rockwell. Lacy, in fact, first got to know Spielberg because she interviewed him on Rockwell for her PBS series American Masters.

If exploring Spielberg’s childhood and revisiting his most lauded directorial works are the first two pillars of Spielberg, the third is most definitely a candid assessment of the director’s relationship to his faith. In short: it wasn’t always easy. Spielberg describes, in touching detail, the embarrassment he felt hearing his Russian grandfather call “Shmuel, Shmuel!” from the front steps of his suburban Arizona home, as he played with friends down the block. Of course, some might see this as an experience universal to American Jewish children (outside of ultra-Orthodox sects) from Spielberg’s born-in-the-New Deal generation — what kid of that era wouldn’t be susceptible to the self-consciousness of this moment? But for Spielberg, who was raised Orthodox, it didn’t fit with that “Father Knows Best” image he craved, and when his relationship became strained with his father in his teen years, so too did his faith.

The documentary reveals that it was his marriage to Kate Capshaw (meeting her was like hearing “bells ringing,” he tells the camera) and her conversion that brought Steven back to Judaism. The film also draws a connection between this shift in thinking and a sea change at that moment in his work. Crediting his second wife with a renewed focus on authenticity in filmmaking, he says he got to a point where “truth began to upstage make-believe.” He and Capshaw married in 1991; in 1993 Schindler’s List premiered, in 1997 he directed Amistad, and in 1998 came the WWII epic Saving Private Ryan. The shift was fortuitous: the director won an Oscar for directing both Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan, while Amistad was at least a critical if not a commercial success.

But Saving Private Ryan was also the year’s highest-grossing movie in America, which brings us back to the most pervasive question about Spielberg: is he a populist or an artist? Critics will keep the debate open, but Spielberg is a definitive defense of his earned right to be seen as both. “I think he is a genuine artist, and he has really good commercial instincts,” says Lacy, his most in-depth biographer to date, “and they can exist in the same person. And they always will.”

Featured image: Steven Spielberg. Photo: courtesy of HBO