“The Last Showgirl” Director Gia Coppola Pulls Back the Curtain on Pamela Anderson’s Career-Defining Performance

For a film set in Las Vegas, it’s surprising that director Gia Coppola chose grit over glitz for The Last Showgirl.

“I wanted to make a movie in an intimate way. I adore [John] Cassavetes and how he made movies,” says Coppola, who cites Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie as “one movie I looked at for sure.”

Coppola worked from a script by Kate Gersten, who adapted her own play. “By staying intimate, I get to keep my creative autonomy. When I came across Kate’s play, it lends itself structurally to doing a movie in that way. There are not a lot of locations and a small cast, so you can be insulated,” says Coppola, granddaughter of filmmakers Francis Ford Coppola and the late Eleanor Coppola. She began collaborating with producer and Coppola cousin Robert Schwartzman in 2021, opting for a modest budget and an 18-day shoot to keep creative control.

The Last Showgirl pulls back the curtain on a fading Las Vegas act called Le Razzle Dazzle, a Follies-like extravaganza featuring scantily clad chorus girls in giant headdresses. Le Razzle Dazzle is based on Jubilee, the last show of its kind in Vegas, which closed in 2016 after 35 years.

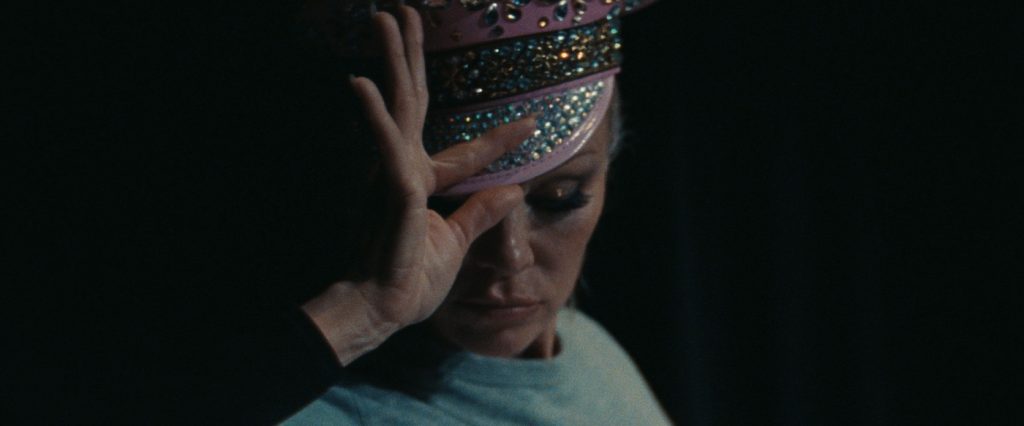

The film is anchored by Pamela Anderson’s tour de force as Shelley, who’s been with Le Razzle Dazzle for three decades and proudly sees herself as carrying the tradition of Les Folies Bergere. Shelley may be a bit delusional, but her dedication, professionalism, and pure heart are endearing and even noble. Anderson is being lauded for a role that mirrors her own career and reveals a depth few knew she had. But with the show about to close, Shelley is dismissed by the entertainment industry since she’s no longer useful and treated as a joke since she’s no longer young. Her college-age daughter Hannah (Billie Lourd) arrives to question her mother’s choices, and Shelley makes no apologies despite being painfully aware of the price she’s paid by focusing more on her career than on motherhood.

“I wanted to tell a mother-daughter story for a long time. I was raised by a single mom, so it’s very meaningful, and then I became a mother myself, so I understand that aspect of motherhood,” Coppola says. “But it’s also a story of chosen family and the workplace family, and a lot of people can relate to that.”

Coppola said she’s been drawn to “the landscape of Las Vegas” for a long time. “I always wanted to tell a story there. I was a photography major in college; I would drive cross country and always stop in Las Vegas to take pictures and wonder what the day-to-day life was like there. So, for all of that to be in one script, I couldn’t ask for anything better. I was like, ‘Please, Kate, let me be the one to do this.’”

Coppola was inspired by nonfiction views of Vegas, from documentaries to the work of the late journalist and art critic Dave Hickey, who lived in Las Vegas from 1992 to 2010.

“I didn’t look to movies for inspiration on this project; I was looking to photography. I knew this world because of that,” she says.

For the textured, intimate look of the film, Coppola reunited with cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw, who shot Coppola’s 2013 directorial feature film debut, Palo Alto, and her most recent, Mainstream, in 2020. Arkapaw shot The Last Showgirl on 16mm film to capture a raw, grainy quality, the director says, with Arkapaw using a handheld camera and custom anamorphic lenses.

“We came up together in some ways; she’s gone off and done Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, so we were fortunate to get her back for our small film,” says Coppola. “She used a handheld and stripped off the lighting budget so we could shoot on film. I trust her wholeheartedly. She can do whatever she wants, and I can focus on the actors and story. Most of the crew were women; it was who I gravitate toward and what felt right for this project.”

That includes Coppola’s mother, costume designer Jacqueline Getty, who coordinated all the contemporary outfits and selected various showgirl outfits. But Le Razzle Dazzle‘s actual costumes and headdresses are the original Bob Mackie pieces from Jubilee “that have not left the building in thirty years,” says Coppola. “We were fortunate that we got to use these pieces; otherwise, this would not have worked. A lot of choreography went into making it look like the dancers had been doing this for thirty years. We had a lot of Jubilee dancers come in and show us how to handle the headdresses. The dancers usually walk for just three minutes, but we were doing a movie so [the actors] must hold for longer. Their necks were cranking; they are giant and heavy pieces.”

The focus on character and the intimacy of the setting serves The Last Showgirl’s themes about how the entertainment business discards women as they age.

“I see it all around me. It’s a systemic issue,” Coppola says. “I see it with working mothers; I feel it in my own life as a working mother. It’s a juggling act and a sacrifice, and it’s hard to do both. I see it economically. I see it culturally, even as simple as going to the market and a machine taking over someone’s job. As things get older, whether it’s architecture to humans, it’s only more interesting. Why has our culture so easily discarded all that in exchange for consumerism or something overly sexualized? I hope my journey with this project is about how we can find a way to embolden the past and pay tribute as we forge our modern paths.”

The Last Showgirl is in theaters now.

Featured image: Pamela Anderson in The Last Showgirl. Photo by Zoey Grossman