“Nosferatu” DP Jarin Blaschke on Giving Robert Eggers’ Masterful Vampire Tale Its Bite

Horror fans were given a fresh infusion of Dracula mythology on Christmas Day courtesy of Nosferatu. Written and directed by Robert Eggers, the gothic tale, set in 1838, follows the bloodsucking Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) as he preys on beautiful Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp) and her new husband (Nicholas Hoult). Nosferatu boasts an impressive supporting cast who are, like its stars, all-in on yet another of Eggers’ deliciously detailed period pieces, including co-stars Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Emma Corrin, and Willem Dafoe.

Shot mainly at Prague’s Barrandov Studio and inspired by F.W. Murnau’s 1922 film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, the movie marks Eggers’ sixth collaboration with cinematographer Jarin Blaschke. Oscar-nominated for his black-and-white filming of 2019’s The Lighthouse, Blashcke deployed mood-evoking light and meticulous camera movement to conjure a sense of Central Europe-rooted dread. “My dad was an engineer, and his dad was an engineer, so sometimes I approach things as an engineering problem,” says Blaschke. “If I don’t want the camera bouncing off around the room, how can I engineer the shot elegantly by trimming away all the excess? For me, the experience of watching a film should be as clean and pure as possible.”

Speaking from his new home in London, Blaschke talks about the power of single-take scenes, praises 35 mm film, and breaks down Nosferatu‘s slow and spooky reveal of the shadow-cloaked Count Orlok.

Nosferatu transports viewers to this 19th-century realm of horror in a completely absorbing way.

We tried to make something that had an effect adjacent to hypnosis.

Lily-Rose Depp as Emily delivers an unnerving performance when she’s in the throes of possession. It seems like your camera captures her climactic breakdown in a single unbroken take.

That came out of the rehearsal room. Robert’s there with the movement coach and Lily. We have a conversation about, “Here’s the bed; that’s where the wall would be.” They put [the action] in a certain order. Then I meekly hold up my hand and say to Lily, “Well, what if you did it in a different order so I could get it all in one [camera] move? If you did the shaky bit first and then the backbend—would that still work for you?” I look for a three-act structure in the [camera] movement: What’s the right energetic sequence, and how do you get the camera there?

There are several one-take scenes featuring several actors who must hit their marks and speak their lines without any mistakes. Was that stressful to pull off?

I understand that some people will push back because we pre-position the camera and then put the actors in the shot. But remarkably, the actors in Nosferatu seemed to like the live tension of doing sustained scenes. It’s lovely to watch things melt away where you’re being led but not fed.

You shot Nosferatu on a 35-millimeter celluloid film. Why?

I just think there’s more complexity and subtlety to the color with celluloid film. With digital, if you have mixed light, it’s orange and blue — very clean-cut. But with film, it can get messy in a really nuanced way that I like.

Most of the movie was made on a soundstage in Prague, right?

We went to eastern Czech Republic for a couple of exteriors and built a gypsy village on a farm estate outside of Prague but other than that, yeah. Our production designer, Craig Lathrop, and his team built the castle’s interiors completely on the soundstage. And I had my specifications. I needed sets raised so I could have lights bounce up from underneath and come back through the windows, or sometimes, I’d need a bunch of space on one side and not the other. And there were a lot of discussions about how to move the camera. If it’s a crane shot, they’d have to maybe take a wall out and build stuff with a remote head on a crane in mind, allowing us to go in a straight line. That also means they had to line up the doorways. You could do a kind of fish around, but our camera doesn’t want to fish around. You want this relentless, uncanny camera [movement], and you want it to be precise.

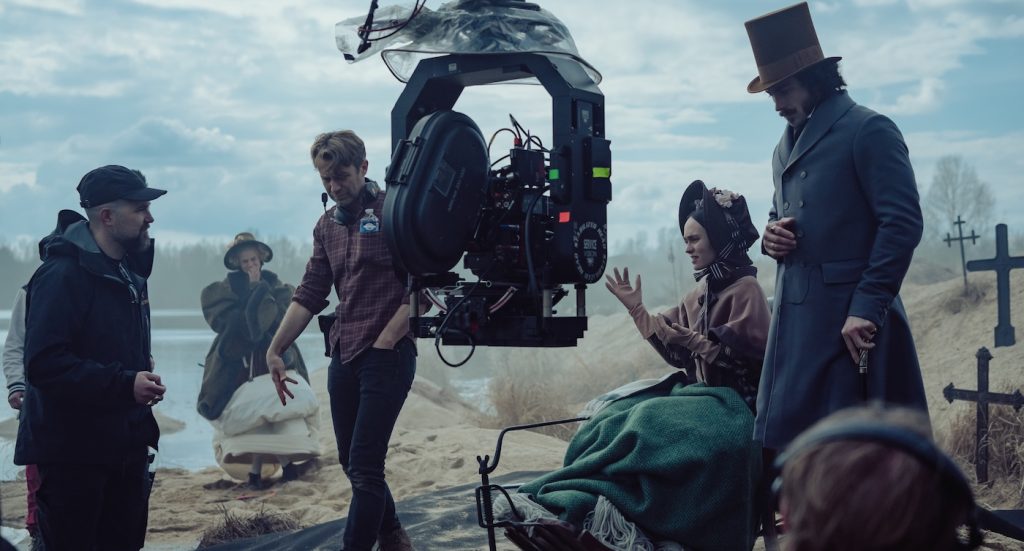

Credit: Courtesy of Focus Features / © 2024 FOCUS FEATURES LLC

Several shots position the character’s face dead center, almost like a formal portrait. How does that level of symmetry reflect your aesthetic?

If you pause the movie at any point, I want the frame to work. With other directors, a lot of time, the first week, they’ll be, “Okay, let’s do a rehearsal, and we’ll find it in rehearsal,” and I’m like, “That’s putting the cart ahead of the horse here.” For me, it’s about planning a series of frames and then figuring out how to move the camera. And then we place the actors.

Credit: Courtesy of Focus Features / © 2023 FOCUS FEATURES LLC

So, camera moves come first?

The actors go where the camera wants. That [approach] came out of The Northman, which is all about fate and how everything’s inevitable, so there’s not anything you can do about it. Similar logic here in Nosferatu. We frame to the architecture, especially in an oppressive magical castle, and then you put the actor’s action there. We wanted to create illustrative images that give you a storybook feeling.

There are basically no over-the-shoulder shots in Nosferatu. Intentional?

When you go to a photo gallery, do you ever see an over-the-shoulder shot? That’s not a good picture! That’s not a portrait. How many out-of-focus shoulders do you need in your movie? It’s not a good frame.

Do you have a background in still photography?

Not professionally, but I’ve had a camera since age ten. [Jarin gets up and retrieves a binder from a book shelf]. This is binder number 20 of negatives that I started collecting in 1994. Still photography definitely offers ideas I can explore in our movies.

Lighting plays a huge role in Nosferatu, creating atmosphere and shadows. The moonlight, the candlelight, and the firelight all seem very organic.

I’ve learned most of my lighting through trial and error for the last 20 years after film school, just from observing things in the world. Like “This scene would be great if it looked like that cathedral I visited in some European city during the winter. What would the colors be? What angle would the light be?” I want the audience to believe that this is what a Transylvanian nobleman’s castle really looks like. I’m not going to set up a backlight that wouldn’t be in the room. Or moonlight: What does that look like for me at night? Well, I don’t see color. That answers the questions in a really clean way.

Credit: Courtesy of Focus Features / © 2024 FOCUS FEATURES LLC

You’ve teamed with Robert Eggers on six movies now. How did you guys collaborate on the look of this film?

Sometimes, it’s hard [to figure out] what’s Rob and what’s me, but Rob likes the symmetrical frame for sure. He’s very classicist. He got as far forward as the Renaissance and saw no reason to go into anything else. [laughing]. In this context, it works because our story is set in 1838. The way we see things in Nosferatu is inspired by the taste of the characters in the movie and the era they represent.

When we first see Count Orlok in his castle, he’s lit and photographed as a shadowy figure. Can you break down the slow reveal of this mysterious character?

All the ways you could obscure this person, we used them all! Silhouette with the lights behind him. Then we cut to the other side where Thomas is front-lit, but you only get Orlok’s back and his hands. At the end of the scene, Orlok is front-lit, but you do a chop and only see his hands because everything above is dark, or it’s a shot of his eyes, so you don’t see the rest [of his face]. Every which way, we exhausted all the options.

Credit: Aidan Monaghan / © 2024 FOCUS FEATURES LLC

What kind of equipment did you use?

Panavision Arriflex. Arricam ST camera. We shot on Kodak 5219 stock. For the dream sequences, I used a lens based on a 19th-century design. We also had high-speed lenses made by Panavision for our production. We went through five different versions. One had too much character, and Another was too clean. Version number five was great.

Why did you need a new type of high-speed lens?

To capture the candlelight. In the [gypsy] inn, for example, we’re able to see the old grandma with a single candle, and you can actually read the lighting on her face. I wanted to use real fire, as opposed to The Witch or The Lighthouse or The Northman, where we simulated firelight, but it wasn’t actually fire.

Being able to work four months on this movie must have meant a lot, economically, to the camera department you assembled for Nosferatu. What kind of qualities do you look for in your crew members?

I want nerds. Even though I’m a very technically oriented person, I tend to get along with actors even more than crew members because actors really put themselves into the work. Those are the kind of people I’m looking for.

Featured image: Lily-Rose Depp stars as Ellen Hutter in director Robert Eggers’ NOSFERATU, a Focus Features release. Credit: Courtesy of Focus Features / © 2024 FOCUS FEATURES LLC