“Dune: Prophecy” Cinematographer Pierre Gill Captures the Many Moving Pieces of a Dangerous Game

A frequent collaborator with director Denis Villeneuve, award-winning cinematographer Pierre Gill respects the filmmaker’s legacy but also relishes being able to play in the same sandbox and create his own vision with Dune: Prophecy.

A prequel to Villeneuve’s Dune films, Gill maintains the epic scope of the universe in the three episodes he directed, including the pilot and finale of the acclaimed six-episode HBO show, which focuses on the origins of the powerful, secretive sisterhood known as the Bene Gesserit. Tasked with establishing a look for the show, set 10,000 years before Dune and Dune: Part Two, he shot 75 percent of his episodes in camera [meaning using practical effects and designs rather than CGI] and using an almost entirely local Hungarian crew.

Here, Gill explains how he used everything from eyeliners and necklines to silhouettes and Danny Elfman’s Batman theme to help him create tension and identity in the science fiction series visuals.

What were your first creative thoughts when you read the scripts for Dune: Prophecy?

It was really fun, actually. A really cool thing happened in the scripts: You discover things that are related to Denis’ movies, which is good information. The films are complex, and it’s good to have more pieces of the puzzle. I get involved if the script touches me. It’s often very hard to read sci-fi because there are a lot of things like, ‘Exterior Salusa: The spaceship lands.’ Well, what the hell is Salusa? What does it look like? Unless you read something like Star Wars: Episode V, where you know the universe, it’s very difficult to understand what’s happening. This one was like, ‘Okay, it’s 10,000 years before, so what does it look like?’ My mind stayed in the Dune universe of Denis. Right away, I saw in my mind things like the Sisterhood and felt it would be great if this planet was always stormy, dark, and gray. Then I thought the other place should have a high sun, with a very bright, white light. I wanted to make sure you know where you are. It’s a TV series, not a movie, meaning there are going to be more scenes and more sub-stories, and you can get lost. It was clear to me that as I was reading it there were two worlds and then a third one, which you get to see as the series progresses.

Something you carried across from the films but made your own is the stark geometry.

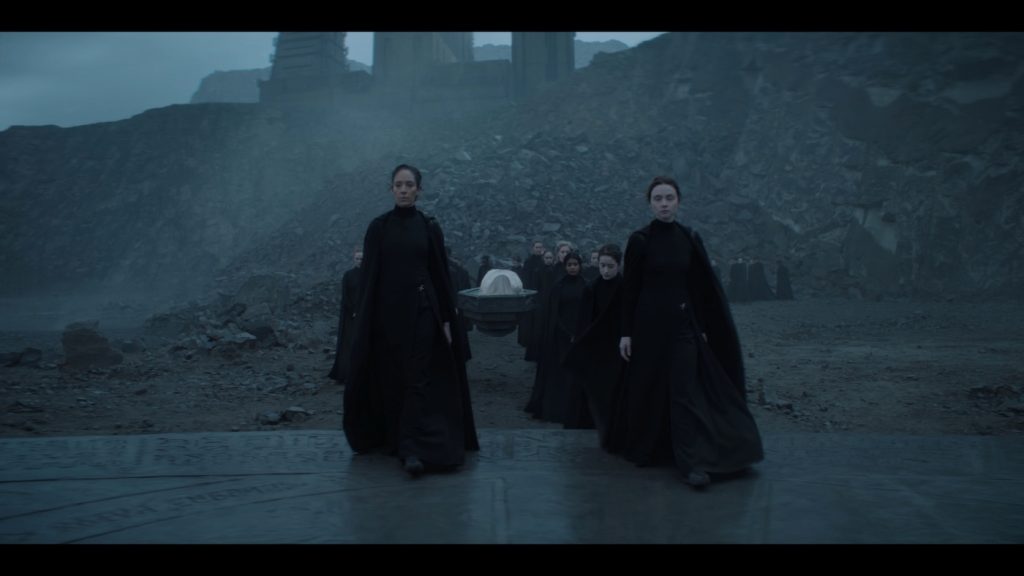

The production design is really cool. When I got there, the Sisterhood was being built, and it was not straight. It’s crooked on purpose. There’s not one line that is actually a real vertical. It’s really crazy because once you start to do symmetrical, it doesn’t work. All of it is on an angle. It’s a decision to break the equilibrium and make it more strange and lonely. It’s very stark. I was trying to cheat the camera, sometimes going as far back as we could with the actors so there’s more background. I was trying to embrace the sets as much as possible. If we did a scene around a table that’s in the middle of a room, when I do all the coverage, I would bring the table to the side. The audience doesn’t see that but there’s more background, it’s bigger. I was trying to keep it in scope. About 80 percent of the set was built, so it was huge; it’s gorgeous.

How else did you use framing to give an identity to characters and locations?

What I really like to try to achieve is that the eyes of the audience go to the eyes of the character. If they’re small in a room, I want you to look at their eyes. If you’re super close-up, I want you to look at the eyes. I don’t like to have messy frames. I like it when it is eyes to eyes. I will work on the lighting or shadow as much as I can. I wanted to shoot anamorphic to be closer to the actor with the camera, so you feel them, and it’s not as flat. However, because you’re closer to the actors, they end up looking at each other sideways, which I don’t like. I was stripping the camera so an actor could be tight against it and see the other actor, but just barely. It’s very powerful. It’s one of Denis’ strengths. You look at his shots, and you really feel the actors. Of course, they’re gorgeous and photogenic, but when you look at it, the eye line is dead on.

Something I noticed in your close-ups is that you tend to include necklines. Why?

I don’t like to have a head floating in space. Once you start doing television, you start to think you have to do a big close-up, but a lot of people are still going to watch it on a 55 or 60-inch TV, which is pretty big. Even on an iPhone, it doesn’t look small when it’s well achieved. For example, Valya Harkonnen has this incredible necklace, and I was like, ‘Go back. Keep the necklace in there.’ It makes them a bit stronger. You’re not telling a story with kids wearing a t-shirt in a cafe, and you don’t really care. The costume is very important, very strong, I love to incorporate it. I also like to see the hands as they tell a lot about the character.

There are a lot of epic scenes where you only see the silhouette of a character. How and why did you want to use those?

I would have done much more of it if it had been possible. I think it gives a very powerful mood and gives the audience a chance to participate. If somebody is in silhouette, you’re intrigued, but you have a connection. First of all, it’s gorgeous, and it has a romantic element. In episode one, young Valya and Dorotea stop in a big room, and I get them to be silhouetted. We did this shot, and everybody was like, ‘Oh, wow, it’s amazing,’ and the great thing about it is that they talk, and you listen completely to what they say. I was very happy because they kept it in the edit. The silhouette goes with the beauty of these types of movies and shows because they are part of the architecture. You have an arch, then you have a small character, and it makes them part of the world and puts them into their environment.

You shot this in Budapest. Did you use a lot of local talent?

I have shot in Budapest many times. I filmed The Borgias there, went back for Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Casanova, and did Blade Runner 2049 second unit for Roger Deakins and Denis Villeneuve, but I think I’ve gone back there about six times in total. For certain reasons, I will bring my own Steadicam operator and focus puller, but the camera crew and assistant focus pullers were Hungarian local crew. I only bring three or four people. Some people bring 10 to 15 crew members, but now I use the gaffer, grip, SFX, DIT, and all of them in Hungarian. I know the three main crews that can do a production like this. These are humongous productions, so you need a very strong people. I’m very proud to say that 90 percent or more of my department was made up of the Hungarian crew.

There are a lot of scenes in Dune: Prophecy that are very still. How did you find movement in those so that they didn’t feel stagnant?

It’s a good question, but it’s difficult to answer because when there’s a lot of dialog, it’s hard to nail down when and how to move. We could do an interview just about this. Sometimes, we decide, ‘Okay, we’ll move on this line.’ Sometimes, you’re not sure because the scene is being built. That’s a fun part of filmmaking. I have the main operator that I bring with me; he’s my Steadicam guy, but we have the camera on a Technocrane most of the time. I had two Steadicam operators all the time, so I have them working around and making ballet. I talk to them a lot via a headset and build it live. With some scenes, we establish a very slow drift, so there’s a buzz going on all the time. It works pretty well. A lot of it is made on the crane, where we creep in slowly, stop, and then wait and creep again. It’s very precise. I’m always doing the Danny Elfman’s Batman theme in my head, so I can tell my crew, ‘Okay, you’re moving too fast,’ or, ‘It’s too slow.’ It’s that level of subtlety. Most of the time, we try to keep it elegant and strong. You’re doing many more scenes with a TV show, so you must build your show in the editing. I drive the movement to make sure I know it will not get annoying in the editing. There’s nothing worse than a camera that moves too much, or it cuts during a movement. It’s important to keep a nice flow.

Dune: Prophecy is now streaking on Max

For more on Dune: Prophecy, check out these stories:

Official “Dune: Prophecy” Trailer Unveils a Powerful Sisterhood Rising in a Troubled Universe

Featured image: Courtesy of HBO.