“Merchant Ivory” Director Stephen Soucy on His Must-See Doc for Film Lovers

The name Merchant Ivory is so synonymous with lustrous period films, particularly literary adaptations of the works of E. M. Forster and Henry James, that even some astute filmgoers assumed it was a studio or a brand. It was both those things, but it was foremost the names of two men—US-born director James Ivory and India-born producer Ismail Merchant—who together formed a partnership that changed modern moviemaking.

That’s the major takeaway from Stephen Soucy’s illuminating and entertaining documentary Merchant Ivory. It details how the filmmaking team that included writer Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and composer Richard Robbins managed, against the odds, to bring so many luminous classics to the big screen in the 1980s and ‘90s such as The Bostonians (1984); A Room with a View (1986); Maurice (1987); Howards End (1992); and The Remains of the Day (1993). Besides this rich film history, the film offers a delightful behind-the-scenes look at the often tumultuous personal relationship between Merchant and Ivory, a couple from 1961 until Merchant’s death during abdominal surgery in 2005.

“The Merchant Ivory story is the iceberg above the water, but there was all this big stuff beneath the water’s surface that I wanted to navigate through,” says director Stephen Soucy. “They were such fiercely independent filmmakers from day one and for many, many years. They didn’t even get into the studio system until the ‘90s.”

A theater producer who’s made several short films, Soucy directed the animated short Rich Atmosphere: The Music of Merchant Ivory Films in 2019. The film focuses on composer Robbins, who scored 21 Merchant Ivory productions. It impressed James Ivory, now 96 and the only living member of the Merchant Ivory quartet.

“I interviewed him twice, then brought the finished film with narration and super cool animation that Jim loved. He was over the moon with it. So I sensed an opportunity,” said Soucy. “I said, as a huge Merchant Ivory fan, [he should] let me make the definite look at what Merchant Ivory was.” Even though Soucy had not yet made a feature film, Ivory said yes.

“That’s very Jim. Many people, such as Maurice producer Paul Bradley, said that when they first started with him, they didn’t have much experience. But Jim gave many people the chance, and they stepped up. I’d only made shorts, but Jim thought I could do it.”

Ivory’s blessing led Soucy to the dazzling array of interviews he assembled for the film, including actors Hugh Grant, Helena Bonham Carter, Vanessa Redgrave, Emma Thompson, Rupert Graves and James Wilby; Jenny Beavan and John Bright, who won an Oscar for their costumes in A Room With a View; and many more who share how much the films meant to them and to their careers but also the struggles of grueling, unpredictable shoots for little money.

The documentary spans the 40-plus films in the Merchant Ivory oeuvre including their early, India-set dramas The Householder (1963), based on screenwriter Jhabvala’s novel, and Shakespeare Wallah (1965), about a troupe of actors traveling across India that took the Berlin Film Festival by storm and put Merchant and Ivory on the world cinema map. There are deep cuts from their later movies such as Slaves of New York (1989); Jefferson in Paris (1995); and Surviving Picasso (1996).

“I wish I could have taken a deeper dive with some films, but you run out of time,” said Soucy. “We came upon the structure of early, middle, then the bigger [films] and ending it with Call Me By Your Name. That idea came from Jim when he told me Howards End was “Ruth’s film.” When we showed [the documentary] at BFI in London, some were disappointed that we didn’t have more about Heat and Dust. But I chose to take a deeper dive into the core films, especially since these were the ones that more people could talk about …. [The structure] occurred naturally based on who was available to talk to me.”

“Emma and Hugh were hard to get. But they were happy to talk about this period. It was a gift to meet with them. Some of the decisions were based on availability; luckily [writer] Tama Janowitz could talk about Slaves of New York, a film I love; it’s such a time capsule.” Soucy said some extended interviews will be posted on the documentary web site.

As Soucy earned Ivory’s trust, the filmmaker opened up about being gay in the 1960s and his relationship with Merchant who hailed from an conservative Indian family. Merchant was also involved romantically with composer Robbins, inspiring the kind of volatile yet genteel drama that propelled their films, particularly with Bonham Carter’s revelation that she, too, was in love with Robbins.

The documentary includes a clip of Ivory, who at 89 became the oldest Oscar winner in history for his adaptation of Call Me By Your Name (2017), when he accepted an award from the LGBTQ organization GLAAD and acknowledged the broad shoulders of his late partners Merchant, Jhabvala and Robbins. He also cited the trial blazed by his own film Maurice. Now considered a gay classic, Merchant Ivory documents Ivory’s singleminded determination to make that film in the mid-1980s, not the most friendly time for queer projects with AIDS at its peak and with Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government enacting the homophobic Section 28.

It was also personal for Soucy. “It was important for me to showcase Maurice. For many gay men, myself included, it was a hugely important film. I was a teenager [when it came out], and it was the first time I saw myself onscreen grappling with the same things,” he said. “I’m proud I was able to showcase the long arc of Maurice and the impact it’s had.”

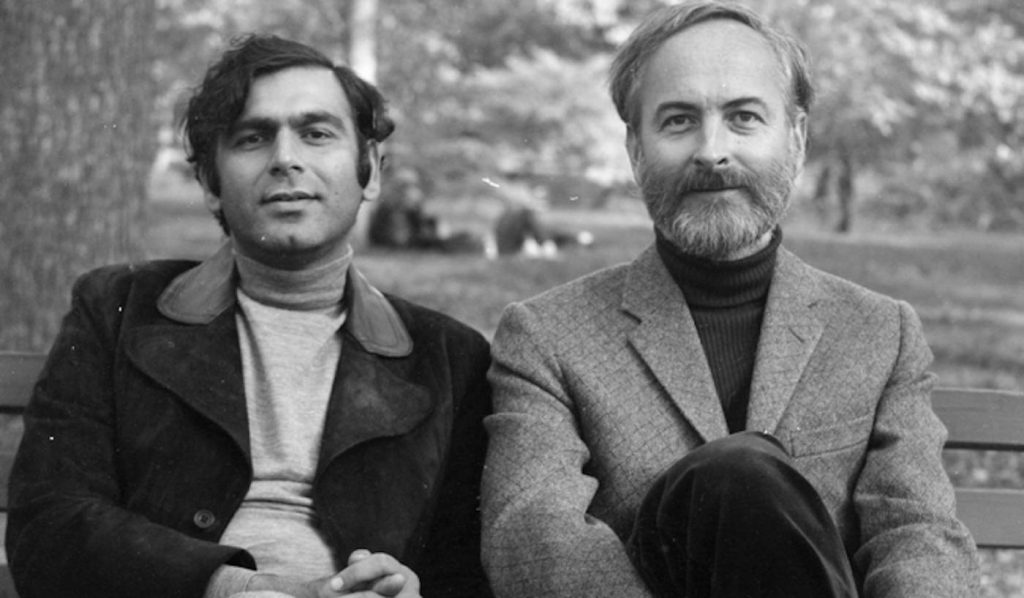

Featured image: L-r: Stephen Soucy, James Ivory