“Jim Henson: Idea Man” Editors On Making a Documentary the Muppets Creator Would Have Made Himself

Ron Howard’s documentary Jim Henson: Idea Man, out May 31st on Disney+, is not only a tribute to the beloved, brilliant creator of the Muppets but feels like an artistic reflection of the creator’s own work. Cutting between Henson’s best-known creations, Sesame Street and The Muppet Show, along with his early short films, commercials, abstract videos, and Henson family footage, the documentary also uses visual effects, stop-motion animation, and regular animation alongside contemporary interviews to show Henson’s non-stop drive to create. And just as Sesame Street toggles between Oscar the Grouch’s garbage can and, say, a claymation short about the number seven, Idea Man toggles between these these different elements in a way that seems perfectly logical.

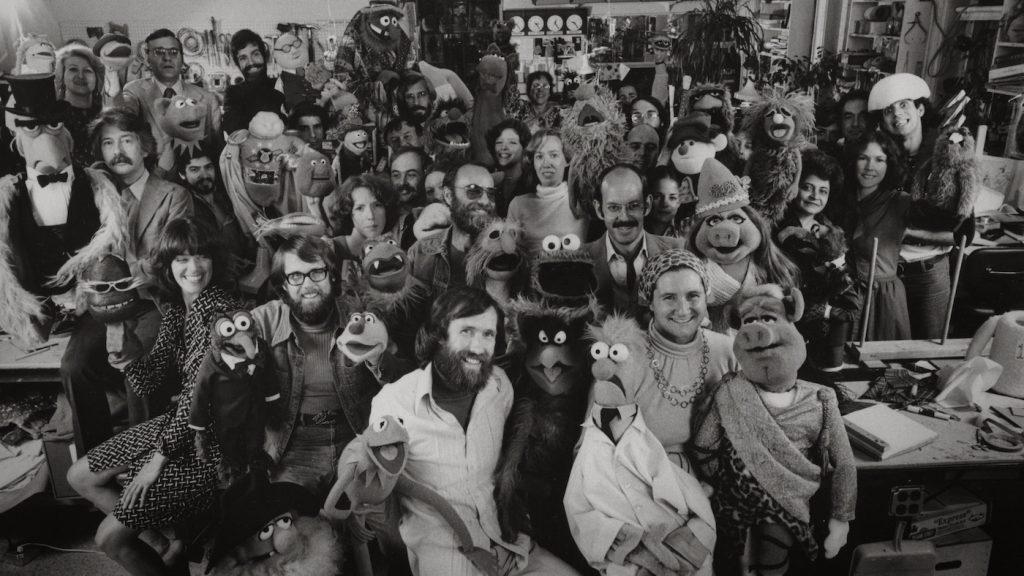

The process started with finding representative gems in thousands of hours of Henson’s work. The volume of “what we had to work with was insane,” said Paul Crowder, who co-edited the documentary with Sierra Neal (previous projects together include McCartney 3,2,1, Pavarotti, and The Yin and Yang of Gerry Lopez). Crowder and Neal went through the output of Henson’s 36-year-long career, coming out the other side with a fresh understanding of the creator’s “affectionate anarchy,” as one documentary subject described the early days of Sesame Street. In addition to combing through endless episodes of Sesame Street, The Muppet Show, and Fraggle Rock, at the Henson family’s behest, the editors visited the Jim Henson Company’s offices to screen footage of the creator’s earlier work, independent films and shorts made from the 1950s onward. This viewing was crucial to the final edit. “We tried to use Jim’s work to tell the story at different places in the film,” Neal said, using, for example, clips from the 1965 short experimental film, Time Piece, to help shape scenes from throughout Henson’s life.

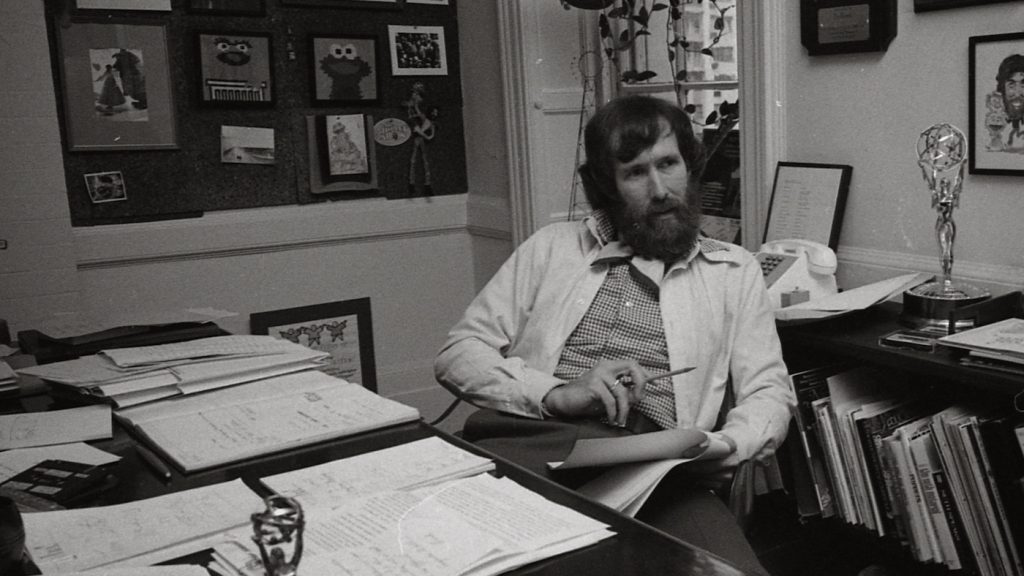

Given the volume of behind-the-scenes footage (Henson’s camera team filmed extensively in places like the creature shop, where the Muppets are made), the editors had a huge amount of material to mine to portray Henson’s career. “It’s a blessing to be able to make an archive film where you haven’t got to cheat anything,” Crowder said. What was more challenging was getting across a private sense of who Jim Henson was. He gave infrequent interviews about himself and comes across as shy, humble, and private in the rare footage where he’s asked questions about his family or how much money he’s making. More typically, “an interviewer would ask him some easy questions and then ask for Kermit to appear, and Kermit would do the rest of the interview,” Neal said.

But conveying what made Henson tick and, thus, what drove him to such dedicated creative lengths is what makes Idea Man gel. “It wasn’t until we really started to get in a little bit deeper to Jim’s life, and his relationship with his wife, his work, his staff, that Ron really pushed us,” Neal said, “and that’s when it started to really come together, and feel like we had a message to put forward.” Interviews with Henson’s adult children (who have their own distinguished careers in art and filmmaking) and co-creators like Frank Oz in a so-called cube, a boundary-less device that allowed for images and animation to be layered with the interview footage was one way into Henson’s personal life. The other was to work as much as possible with past interviews from Jane Henson, Jim’s wife from 1959 to 1986 (Jane passed away in 2013).

Jane and Jim Henson met in a college puppeteering class and had five children together. Despite never becoming its face, Jane was a part of the Jim Henson Company at its founding. A puppeteer herself, she quit working full-time in the 1960s to raise the children, coming back to Muppets projects in the 1980s and 90s. For Crowder and Neal, recordings of Jane’s past interviews, given for print, were among the most helpful finds in terms of detailing the inside story of Henson’s family life, and the production went to great lengths to clean up room sounds from the audio to make them usable.

The editors also used a creative avenue to represent Henson by editing the documentary as he might have done it himself. “The entire team, including Ron especially, was passionate about Jim’s work but was also on board with this idea of making it very Jim,” Neal said. “That meant it was going to be abstract at times. It was going to be a little kooky, and we were going to try to play an oddball joke sometimes.” After screening his lesser-known work, the editors sat down with Henson’s family to ask how he would have approached the project, from editing to additional animation. “We really just leaned into Jim-if this as much as we could,” Crowder said. We learn about this icon who revolutionized television, a shy artist who seemed to forever view himself as a tall skinny kid with difficult skin, not just from behind-the-scenes footage and interviews with his family and closest collaborators, but from a lively, effective edit of this footage creatively unified with choice gems from 36 years of his body of work.

For more stories on 20th Century Studios, Searchlight Pictures, Marvel Studios and what’s streaming or coming to

Disney+, check these out:

“Captain America: Brave New World” Adds Giancarlo Esposito’s Mysterious Villain

Hugh Jackman on the Secret to Bulking Up to Become Wolverine Again

“Deadpool & Wolverine” Reveal Popcorn Bucket Set to Rival Infamous “Dune: Part Two” Offering

Featured image: “Jim Henson Idea Man” takes us into the mind of this singular creative visionary, from his early years puppeteering on local television to the worldwide success of Sesame Street, The Muppet Show, and beyond. Courtesy Disney+.