“Lakota Nation vs. United States” Director Jesse Short Bull & Editor Laura Tomaselli Bring a Profound Injustice to Life

Director Jesse Short Bull knew he’d found the right collaborator in editor Laura Tomaselli when he watched her early cut of Lakota Nation vs. United States, their documentary about the Lakota’s ongoing quest to reclaim the Black Hills of South Dakota, sacred land that was stolen by the government in violation of the Black Hills treaty of 1868.

“Laura cut an amazing scene with a ‘50s western where a man and woman are in a wagon signing about the Black Hills and why ‘the Indians fight so hard for their land,’” recalled Short Bull. “For someone who grew up far from Lakota country, she gets it, and she can see beyond the things we get hung up on in day-to-day life [such as] native versus non-native; Lakota versus non-Lakota. Laura could see it, and I knew from that moment.”

The use of familiar Hollywood clips featuring heroic white settlers and villainous Indians is jarring in the documentary since it exposes an often hidden, long, and shocking history of government-sanctioned betrayals, deception, and brutal massacres. “My mother’s generation watched Gunsmoke and Shane and spaghetti westerns. Some people have no clue about indigenous history,” Short Bull said. The use of Hollywood film clips “showed me how effective our film could be beyond education and entertainment. It has the potential to register with people on the deepest levels. It’s something people recognize deep in their psyche, but we turn it on itself and show people what was really going on though they didn’t realize it at the time.”

Lakota Nation vs. United States, which won best documentary in June at the Provincetown International Film Festival, opens in New York on July 14 before expanding to additional cities on July 21. Short Bull and Tomaselli, who co-directed the film, wanted a textured approach to a story that blends past and present and juxtaposes truth and myth.

“We didn’t want people to feel blame; it wasn’t about ‘how dare you.’ We wanted to get around the walls people have up that [tells them that] this doesn’t matter to them,” said Tomaselli, whose credits include editing the documentary MLK/FBI. By weaving the personal testimonies of Lakota activists with clips from movies such as The Searchers and Calamity Jane, “We thought we would get around the walls and get people thinking that of course this matters, even to non-indigenous people, that we uphold the policies we made,” Tomaselli said.

The narration by Oglala Lakota poet Layli Long Soldier, winner of the National Books Critics Circle award and a finalist for the National Book Award, is the heart of the film as her poetry gives voice to the land itself.

“We can’t interview the Black Hills. And it was paramount to try to capture the Black Hills in the most beautiful way that we possibly could,” said Short Bull. “Once Layli got the chance to know us and what our approach was, then she gave us an amazing structure for this whole film. The language in the treaty itself [says] something that’s not delivered. Language is tricky. We wanted someone who looks at language with a fine-tooth comb, who explores the space between letters, what’s behind a word, and what’s around it? What does it mean if I flip it upside down? Layli does that, and that’s the only way to tell this story.”

Layli Long Soldier recites two poems: 135 Xs and 38. A scene from Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln accompanies 38 and makes a devastating point about the erasure of history. During the same time period as events depicted in the film, Lincoln ordered the execution by hanging of 38 Dakota men as punishment for their role in the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising. It was the largest legal execution in American history. Yet, there is not one mention of it in Lincoln.

Matching the film’s lyrical language is the visual poetry of Kevin Phillips’ cinematography. The voices of Lakota activists, including Nick Tilsen, Krystal Two Bulls, Henry Red Cloud, and Phyllis Young, bring the issues right up to the current moment with footage of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protest at Standing Rock in 2014 and the current Landback movement.

These ongoing efforts to persuade the government to acknowledge and right past wrongs underscore what Tomaselli calls the film’s “radical optimism.”

“The most punk thing you can be right now is hopeful,” she said.

This understanding of the past coexisting with the present is central to Lakota heritage. “History is not a relic; it’s not an old, dusty story that you can’t do anything about. You can make it right,” said Short Bull. “Growing up in Lakota country, I learned that no matter how dark and how hard things can be, you are alive, you have a spirit, and things can always get better. I’m grateful to Lakota country for teaching me that.”

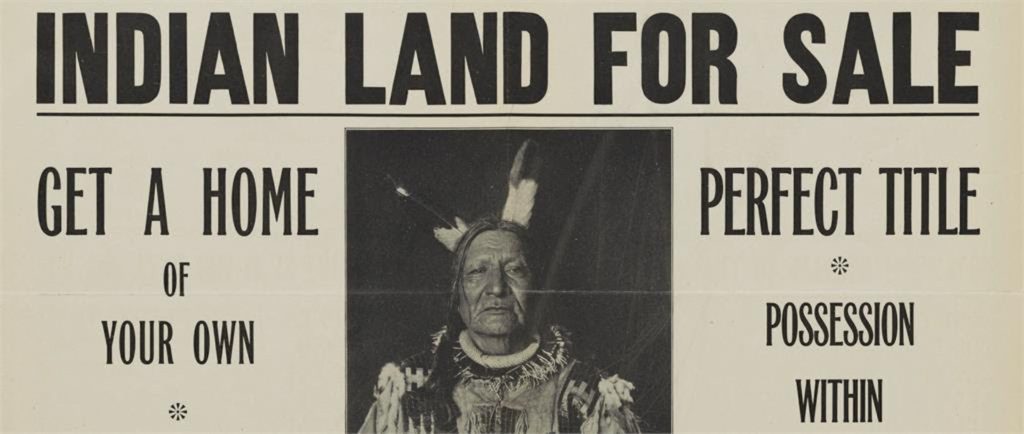

Featured image: A Scene from Jesse Short Bull & Laura Tomaselli’s LAKOTA NATION VS. UNITED STATES. Courtesy of IFC Films. An IFC Films release.