“The Whale” Oscar-Nominated Prosthetics Artist Adrien Morot Breaks the Mold

When it comes to makeup effects, Adrien Morot ranks among the very best. From fierce alligators (Crawl), to mutant superheroes (X Men films X-Men: Days of Future Past, X-Men: Apocalypse, and Dark Phoenix), to this year’s favorite film doll (M3GAN), Morot has proven time and again he’s a prosthetic wizard. But even he wondered if he had met his match when director Darren Aronofsky offered him The Whale.

“Terrified,” answers Morot with a smile during a recent Zoom interview when asked about his initial reaction. “It’s the kind of project that anybody with a head on their shoulders should run away from…the challenge is so immense.”

Based on the stage play by Samuel D. Hunter (who also wrote the screenplay), The Whale stars Brendan Fraser as Charlie, a morbidly obese online English teacher attempting to reconnect with his estranged teenage daughter (Sadie Sink) as he self-destructs by overeating.

Fraser needed to look hundreds of pounds heavier. After reading the script, Morot knew it wouldn’t be easy. Overweight makeups are typical to comedy (The Nutty Professor, Shallow Hal) or sci-fi (Thinner). Each permits a suspension of belief. The Whale didn’t allow for that.

“It’s a chamber piece with a small cast. Nobody’s wearing prosthetics other than the main character. He’s almost in every single scene,” explains Morot. “He’s going to fill up the screen. Any sort of flaw will be immediately noticeable. It’s a prosthetic artist’s nightmare.”

Having worked with Aronofsky in the past, including Mother! and Noah, Morot just couldn’t say no. He would create a makeup unlike any he had done before.

But that was only part of the challenge.

The pandemic was rearing its ugly head. Aronofsky thought The Whale, with its small cast and one location, would be the perfect COVID bubble project. Anticipating a shutdown lasting weeks, not months, the director wanted to act quickly. He scheduled five weeks of prep. Knowing something this complicated usually takes longer, that deadline concerned Morot.

Morot watched the stage production. It created Charlie’s look with padding and wardrobe cheats. This didn’t feel right. “They were using all sorts of tricks to help them out,” Morot observes. “The character is wearing long sleeves, a high collar, those kinds of things. It hides the padding.”

Consulting on the film, the Obesity Action Coalition, a non-profit that advocates for overweight individuals, confirmed Morot’s suspicions. Overweight people commonly wear minimal, loose clothing. “For practical reasons, a lot of skin is exposed,” he explains. “There’s no hiding it like they did in the play. It’s not true to reality.”

Charlie would require prosthetic arms, legs, chest, neck and oversized cheeks. And then there was the shower scene where he’d be totally nude. That added cascading ripples of fat hanging around his midsection. More time was needed to get it right. “If the makeup is a distraction because its show-offy or it’s bad, your movie doesn’t work,” Morot remembers telling Aronofsky.

Aronofksy agreed and expanded preproduction to 12 weeks.

Unfortunately, that didn’t solve another problem. Normally, an actor comes to Morot’s workshop to do a full body cast. This generates molds used to manufacture body parts. But COVID restrictions prevented Fraser from traveling. It was time to push the envelope.

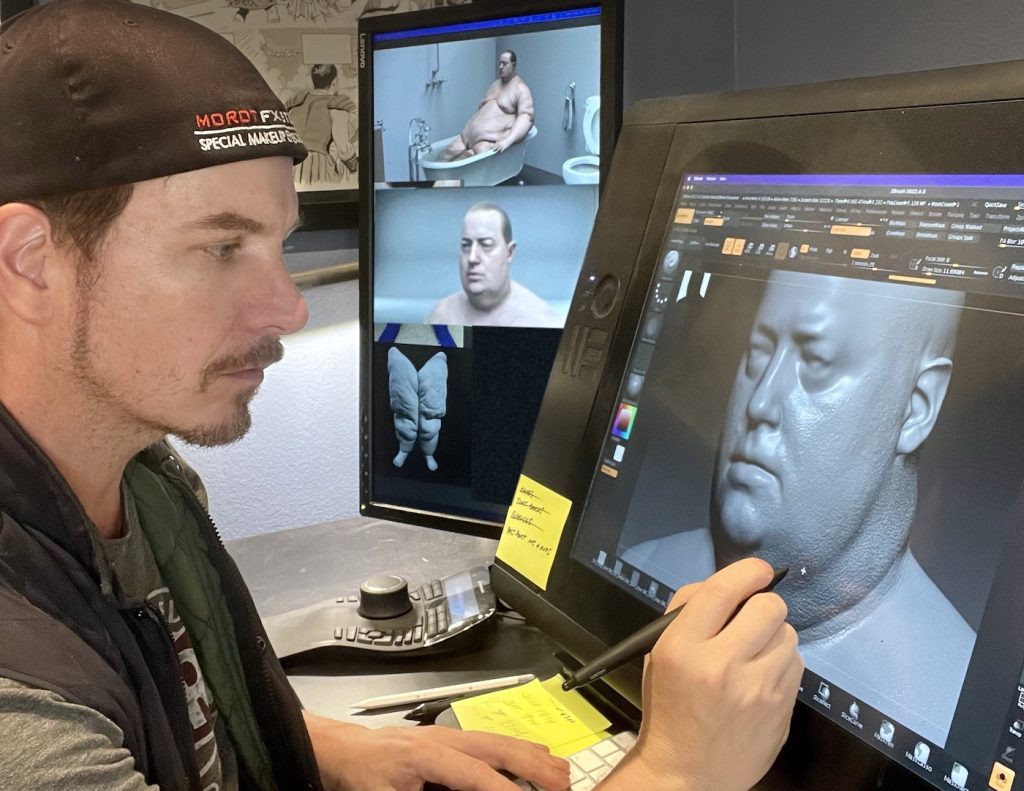

“We’ve been tinkering with 3D printing for a few years — doing internal tests at the shop,” continues Morot. “Makeup effects use 3D printing quite a bit, but it’s mainly robot stuff like M3GAN. The nature of successful prosthetics is doing a seamless transition with the skin. The accuracy of and consistency of 3D technology is not made for that.”

Morot decided to take 3D makeup to the next level. He contacted a colleague with a 3D scanner, asked him to mount it to an iPad and get it to one of the film’s producers. The producer went to Fraser’s house and, at a socially-distanced length, scanned the actor’s body.

“He sent me the data. I was able to clean it up and have a workable model to start the sculptures from,” adds Morot. “And it worked.”

Morot’s design featured two headpieces — one that fitted to the front of Fraser’s face and stretched down to his breast. The other covered his skull and neck. Arm pieces extended to Fraser’s shoulders. Each leg was covered by two pieces. A multi-layered midsection gave Charlie his bulging stomach. Most of the time it was covered by an oversized t-shirt, except for the shower shots.

The first application took seven hours.

“No kidding,” says Morot. “But that’s a lot of tinkering because it’s so heavy. It’s finding the right height so that once it’s glued, it drags to where it’s supposed to land. That takes a little back and forth. Then finding the right palette of color that not only matches Brendan’s skin tone, but also the color palette the DP is using.”

Morot ultimately cut application time to under three hours.

As prosthetics can only be used once, new body parts were needed for each day of shooting. Morot credits Kathy Tse for painstakingly hand punching the hairs that covered Charlie’s arms and legs and gave his face its stubble. She logged a lot of workshop hours to ensure every hair was in place.

The shower scene initiated a crucial change. Because of its lightweight and its resemblance to skin, foam latex is the prosthetic material of choice. But if it gets wet, it acts like a sponge. So Morot switched to silicone. It delivers a similar look, but is much heavier.

“It was like over 200 pounds. So we engineered a sort of parachute harness that would spread the entire weight over his body,” said Morot. He thought Fraser would balk at carrying all that weight, but the actor gladly bore the load. “He told me that it helped him find the character. Maybe he was just trying to be nice.”

Aronofsky had one final curve. He wanted a shot of Charlie rising from a sitting position. Prosthetics don’t work this way. Sitting pieces are shaped differently from standing pieces. A movement like this had never been done before.

“I was like, ‘Yeah, but you’re gonna do a cut…clever editing. Come on buddy, you’ve got to help me out,’” remembers Morot. “And he’s like, ‘No. I want to see it.’”

Morot and Tse spent hours strategizing without a solution. Then Aronosky got an idea. Could the prosthetics be modeled after a Russian doll, where the smaller versions fit inside the larger ones?

“I thought, ‘That’s pretty clever actually,’” remembers Morot. “We ended up gutting the entire thing. Each piece, depending on where it was located, would fit into the one under it or above it,” explains Morot. “After we did those modifications, the pieces collapsed and puddled on the side in a natural shape. When he got up, it would all deploy. Sometimes, I would have to run in and re-jam something. But for most of it, it ended up working. For sure, I’m gonna use it in the future.”

The effort has been appreciated. Fraser received an Oscar nomination for his portrayal. Morot, along with makeup department head Judy Chin and hair department head Annemarie Bradley-Sherron, were nominated for Best Achievement in Makeup and Hairstyling.

“There are so many technological breakthroughs in this movie,” says Morot. “I have to admit, the first day we were on the set, I realized this had never been done before. This is a turning point in movie history and it’s nice to be part of that.”

For more on The Whale, check out our interview with Oscar-nominee Brendan Fraser and the film’s screenwriter Samuel D. Hunter.

Featured image: Adrien Morot adds a bit of glue to Charlie facial appliance while Annemarie Bradley-Sherron styles his hair. Courtesy Adrien Morot/A24.