Oscar-Nominated Makeup & Hair Designer Heike Merker Paints With Mud & Blood in “All Quiet on the Western Front”

Director Edward Berger’s adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front is a painfully absorbing epic. Berger’s take on Erich Maria Remarque’s iconic 1929 novel, captured with astonishing vividness by cinematographer James Friend, teases out the themes in the seminal work about the horrors of World War I with bloody precision. The film wastes no time in depicting the dehumanizing industry of the first mechanized war, in which a dead soldier is stripped of his uniform so that it can be stitched up, resewn, and shipped to Northern Germany, where it will be reused by Paul Bäumer (Felix Kammerer), the young man through whose eyes the carnage of the war is seen. When Paul notices someone else’s name on the label on his uniform, he begins to appreciate the gravity of his situation.

The film follows Paul’s journey, which finds him enlisting in the Imperial German Army three years into the Great War, earning him a relocation to the nightmarish Western Front, where millions of soldiers have already been obliterated along a front line that remains more or less immobile. Berger’s film captures the cruel clash of combat eras that made World War I so horrific, with outdated stationary tactics pitted against the new machines of war, capable of meting out death from afar. The result was a repulsive charnel house of carnage, where 17 million men died in the muck.

To create such a believable vision of war, Berger relied on collaborators like the Oscar-nominated head of the makeup and hair department Heike Merker [nominated alongside Linda Eisenhamerová], who helped turn the film’s cast into credible combatants in a horrific war. Merker also found ways of emphasizing their humanity beneath the layers of mud, blood, and gore they were often covered in.

We spoke to Merker about how she stepped into her very first war movie and stepped out with an Oscar nomination in a production that, while it made her weep, was also shot through with joy.

How did you approach this project initially, before cameras started to roll, knowing the challenge would be immense?

I knew immediately it would be a tough project. My first thoughts were that while I know the book and the time period, I still need to get a feeling for it. I need to get my head more the into the war and the soldiers’ lives. I’ve never worked on a war movie before, so my prep included intense research in watching war movies and trying to find as many pictures as possible from that particular time. Then I went on to documentaries until I found one for me that changed everything, which was They Shall Not Grow Old.

Tell me how Peter Jackson’s documentary changed things for you.

It’s just a perfect entrance into a soldier’s life in the First World War and how terrible it was, how they suffered, how they looked, and how the conditions were. This was basically my door into the project. In that documentary, they were immediately talking about teeth; their teeth were so bad, so that’s why after a while, we gave our actors dirty teeth to get the white and the freshness away. We gave their teeth different colors. In the beginning, we were playing with the idea of breaking their teeth or taking them away or changing them to a silver grill, as some of the soldiers had, but it became all too much and it took away from the actor, so we wanted to have something very subtle, so that became focusing on the story, the actor, and the acting.

Are there any other narrative films that helped you get a feeling for a soldier’s world?

I watched 1917, and I watched films from other periods, like Platoon. Having a new subject, I always need to grow into it. I read the letters soldiers wrote to their relatives or wives at home, and what they described gave me a different feeling. I know it doesn’t have the feel of makeup, but it gives me the feeling of growing into a subject so that I can approach it. To understand them, to support them with the part that I’m there to do.

What was your approach to depicting the horrible carnage of the war?

So you break the script down in sections and you know, for example, at this point, an explosion happens, and Paul’s underground, so he needs to be dirty. He needs to have mud and dirt on his face. So we broke the script down to find out where he needs to be dirtier, muddier, where he’s feeling cold, worn out, fragile, or thinner. We apply all the tools in the makeup and special effect prosthetics world. It was almost like a painting where I painted things on and took them off again. So you break each character down, scene by scene, you decide where you want to go, and then you start testing.

On a practical level, how did you manage to test all these looks to make sure the actors looked exactly right for each and every scene?

First, you book an extra to come in and you try different dirt level stages; what can we do to make him look tired, which colors are the right ones, do we have to thin the colors, thicken them, do we have to put on more layers, can we take some of the layers and have a leftover residue and apply something else? All this testing is done on the extra, so when the principal actor comes, you have a plan and you have it down in stages. And you do that with the whole cast for their particular scenes.

What kind of materials were you working with?

I’ve done other movies where I had people who were dirty or muddy, but here I needed a much bigger range of mud and dirt; I had mud from a very light version in yellow to gradually darker mud and then black, and all different textures. I had this very thin, water-resistant dirt, semi-liquid dirt, and clay versions. You rely on materials you’re used to working with, like grease paint or skin illustrators, too. I have boxes full of equipment, and because you never know what you’re going to need, you carry everything with you.

How many people did you have working with you in your department?

So for the main cast, including myself, we had four people. But after several weeks, we struggled a bit so we hired another person and became five. Then we had a background crew of three on a daily basis. But they had to book additional people in according to how many background players we had. So not a big crew.

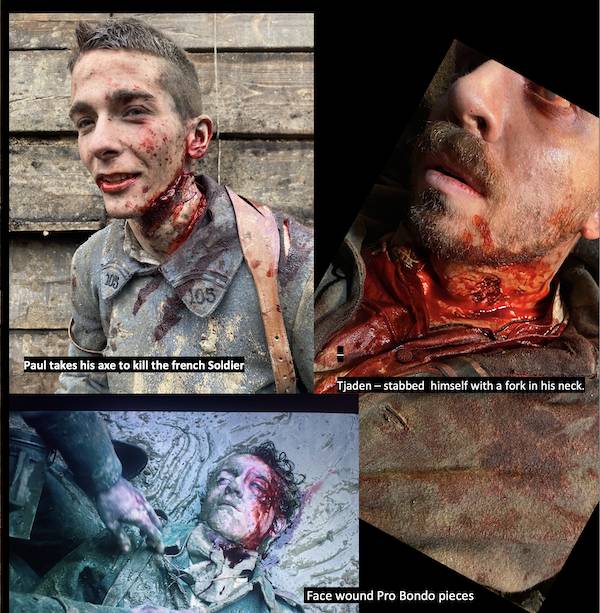

Let’s talk about the wounds, which are plentiful, realistic, and harrowing to behold. How did you and your team approach their creation?

The wounds and gore still fall to makeup and hair, and if it comes to bigger appliances [prosthetics], then I take pictures and draw what I’d like to have and give it to a workshop that can make a life cast of the actor and make the wound. But when it comes to blood and dirt and little wounds, this is still makeup, not special effects or prosthetics.

So you’re drawing wounds by hand?

I’m giving positions and drawing reference pictures of how I think the wounds should look. Like, if the chin is wounded, we have to know how long the actor’s chin is and figure out if it makes sense to have the wound there. We need to know how the wound will play with the costume, and work with the costume department, too. For example, one character got hit on the face, and in his first costume fitting, he had a heavy helmet with a leather chin strap. So we realized we couldn’t do that, so the costume designer [Lisy Christi] took away that helmet so that we could create the wound because it’s an important moment in the story. Then the workshop tells us we have to move the wound up or down because otherwise, it wouldn’t make sense, and then we take that information back to our director Edgar Berger. You figure it out bit by bit. And the prop department is important — what is causing the wound? A bullet? A knife? A wooden stick? Because each has a different impact and creates a different wound. We pored over so many books where we learned about all these different impacts.

What was it like for you emotionally to work on this film, considering the subject matter and all the death you’re depicting?

I had a moment, yes. It’s not the first movie I’ve worked on with heavy situations, and it’s not personal because I know it’s fake. But, there was a moment where you have the crater scene, and Paul and the French soldier are coming together to fight. Basically, it’s a moment where it’s like, okay, you’re German and you’re French—you’re a human being with a family at home. They could be friends in normal circumstances. Paul could go to France on the holidays and be friends with this French soldier and they could have a wonderful life. So this was such an emotional moment that, while they were filming it, I had to cry. It was so intense, and the acting was amazing. Then there’s a technical part of this scene and you have to do the blood pump, and the mud keeps getting shoveled into his face, but of course, it’s not real mud because we had to make something that was okay for him to have in his mouth, so you still have to do your work but it was so extremely emotional I was shocked. I was so happy to end that day. And yet, it was kind of a dream to work on this film…we all enjoyed working together because the group was so fantastic. It was a wonderful collaboration.

All Quiet on the Western Front is streaming on Netflix now.

For more stories on Oscar nominees, check these out:

Oscar Nominee Brendan Fraser on his Deep Dive into “The Whale”

“The Whale” Oscar-Nominated Prosthetics Artist Adrien Morot Breaks the Mold

Oscar-Nominated Sound Designer Frank Kruse Makes Some Noise on “All Quiet on the Western Front”

Featured image: Felix Kammerer as Paul Bäumer in All Quiet on the Western Front, Courtesy of Netflix © 2023