“Descendant” Co-Writer & Producer Dr. Kern Jackson on Uncovering Living History in Mobile, Alabama

The documentary Descendant is about many things, but mostly it’s about storytelling — how oral histories, passed down from generation to generation, inform identity and community and connect the living to their ancestors. History can’t be erased or denied as long as stories are still being told.

Descendant, which won the US Documentary Special Jury Award for Creative Vision at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival and is now on Netflix, follows various residents of the small community called Africatown, now part of Mobile, Alabama, who for generations had heard and shared stories about the slave ship The Clotilda. Owned by wealthy Mobile resident Timothy Meaher, the Clotilda brought 110 human beings from Dahomey (now known as Benin) West Africa to the Mobile region in 1860, more than 50 years after the international slave trade was abolished and considered a crime punishable by death.

To cover his crime, Meaher set The Clotilda on fire and sunk it. The Meahers and other white residents for years dismissed tales of The Clotilda as myth or lore. But the existence of the last slave ship was an “open secret” in Mobile for generations of descendants of The Clotilda survivors.

Descendant also documents a team of marine archeologists as they confirm in 2019 that the charred vessel sunk 20 feet down in the Mobile River is indeed The Clotilda. There are mixed reactions from some of the Africatown residents and descendants who wonder what this might mean for their small community since Africatown is already overrun by heavy industry and factories that spew cancer-causing toxins.

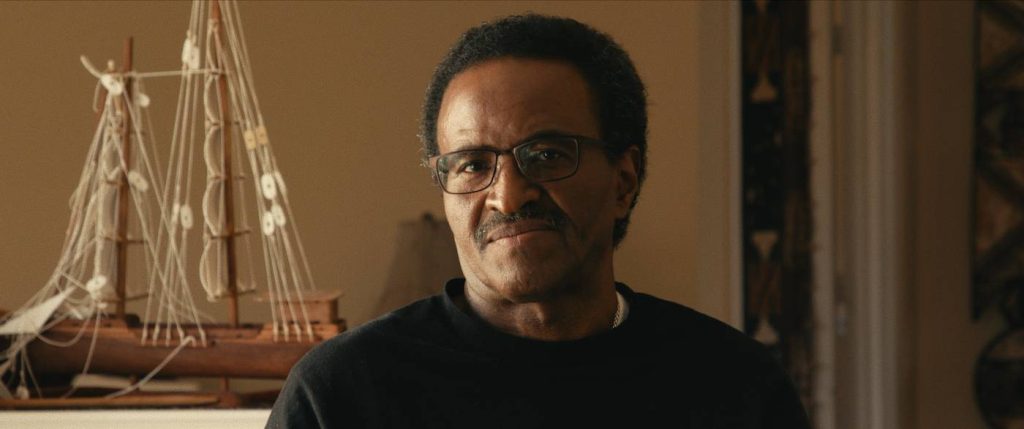

But there was a sense of vindication. “They told their story no matter what,” says Dr. Kern Jackson, the film’s co-writer and co-producer. Jackson is also a subject in the film since, as a longtime folklorist in Mobile and Director of the African American Studies Program at the University of South Alabama, he conducted many filmed interviews with Africatown residents over the years which appear in the documentary. Though not originally from Mobile, Jackson’s connection to Africatown runs deep. His grandmother was the vice principal of a high school in the neighborhood and his Godmother was a counselor and he spent much of his childhood there.

When Mobile started a larger project celebrating 300 years of history, says Jackson, “Nothing was being done in Black neighborhoods. I wanted to explore the neighborhoods of Plateau and Magazine [which are] now Africatown.”

Jackson’s interest and expertise in documenting personal narratives and his deep ties to the community came full circle with Descendant.

“When [journalist] Ben Raines claimed to have found the Clotilda, I picked up the phone and called [director] Margaret [Brown] in Austin. I said, ‘Get here and bring your camera. We’ve got to document this, but particularly, we have to participate in the process to amplify the neighborhood story,’” says Jackson. Jackson had worked with Brown, a native of Mobile, on the 2008 documentary The Order of Myths about Mobile’s still segregated Mardi Gras celebration.

Jackson, along with some of the descendants featured in the film, was concerned about who would take control of The Clotilda narrative; who would profit; and who would be exploited. It doesn’t take long in the film to see that these concerns are well-founded.

“Alabama is not good with transparency,” he says. “Margaret is a wonderful artist who does a movie about her hometown every fifteen years. She is trusted. Margaret is interested in transparency … She does cinema verite but she’s collaborative. Others [were going to] document this so why not go with home folks who know the shorthand and the sensibilities?”

Jackson and Brown had roots in the area and were familiar to Africatown residents. But Jackson says the Descendant team, a mix of Black and white artists including cinematographers Justin Zweifach and Zac Manuel and musicians Ray Angry, Rhiannon Giddens, and Dirk Powell, also worked to earn the community’s respect and trust.

“And it doesn’t hurt to have the drummer from The Tonight Show [Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, one of the film’s executive producers and himself a descendant] or the former President of the United States in your corner,” says Jackson. Descendant is presented by Participant and Barack and Michelle Obama’s Higher Ground Productions.

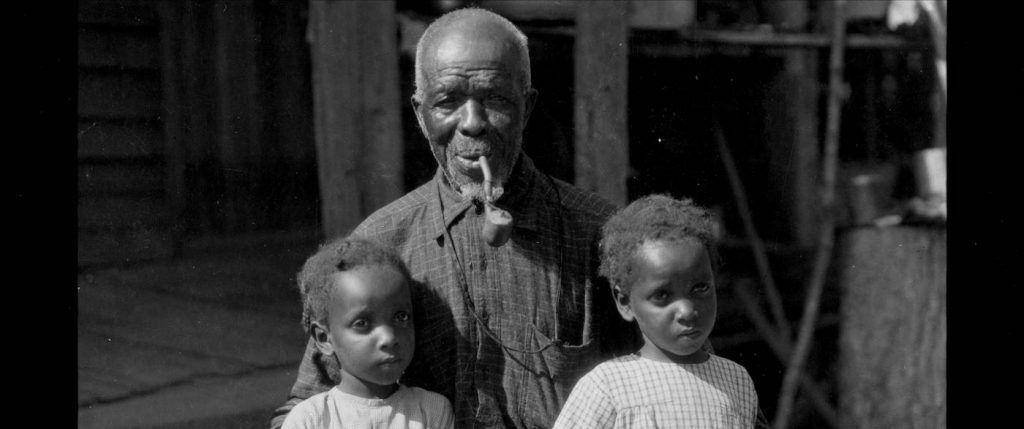

The many Clotilda descendants featured in the film include Emmett Lewis, whose direct ancestor is Cudjoe Lewis. When writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston interviewed and filmed Cudjoe Lewis in the 1930s, footage of which appears in Descendant, he was believed to be the only living survivor of The Clotilda. Lewis’s account of his capture from Africa and the journey on The Clotilda became Hurston’s 1931 book, Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo. But because Hurston insisted on writing in Lewis’s vernacular, publishers rejected Barracoon and it was not available until 2018.

But residents of Africatown continued to know about Cudjoe Lewis and his descendants. His story figures prominently in Descendant.

“The film is a contemplation on how the past is ever-present,” says Jackson.

For more on big titles on Netflix, check these out:

Documentarian Sam Pollard on Courting an Icon in “Bill Russell: Legend”

Trailer for Netflix’s “Bill Russell: Legend” Reveals First Look at the Icon’s Life & Legacy

Sundance 2023: Netflix Nabs Buzzy Psychological Thriller “Fair Play”

Featured image: Descendant. Emmett Lewis in Descendant. Cr. Courtesy of Netflix © 2022