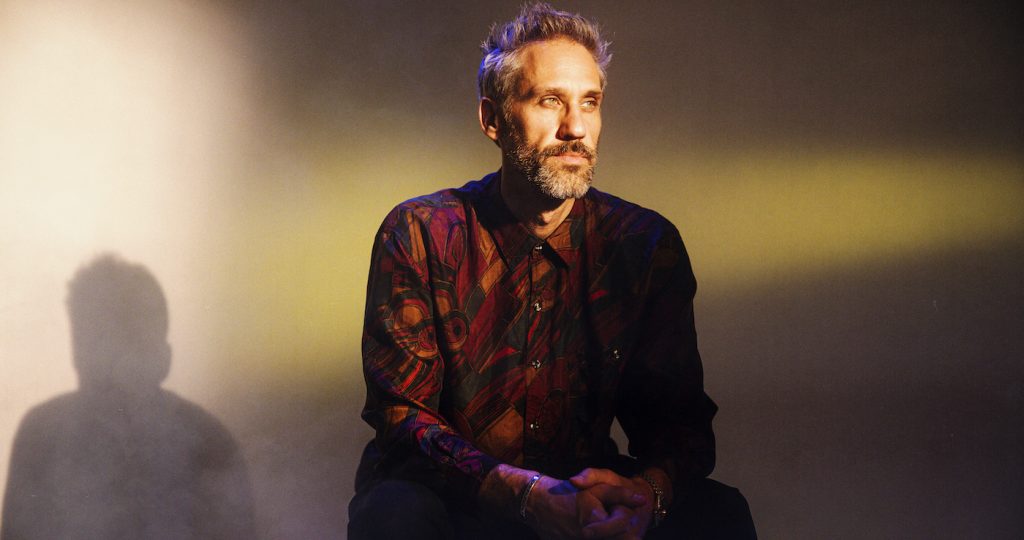

“Ghostbusters: Afterlife” Composer Rob Simonsen on Expanding the Supernatural Sonic Palette

The Ghostbusters are back, but they’ve gotten a lot younger. In Jason Reitman’s follow-up, Ghostbusters: Afterlife (in theaters now), to his father Ivan’s generation-defining classic, Egon Spengler’s (the late Harold Ramis) grandkids, Trevor (Finn Wolfhard) and Phoebe (McKenna Grace) get into the family trade after moving to the dirt farm, a dilapidated Oklahoma property where we learn that Spengler rode out his final years alone, warding off an unusually problematic ghost based in a nearby abandoned mine.

But Spengler’s descendants have no idea what they’re getting into when they show up, reluctantly, at their grandfather’s strange rural digs. Single mom Callie (Carrie Coon) is in dire financial straits, Trevor only has eyes for his crush, Lucky (Celeste O’Connor), and nerdy Phoebe just wants to fiddle with her electronics when she’s not busy with schoolwork. Given her range of endeavors, she’s put out neither about playing chess against the invisible opponent in her bedroom nor at finding herself with her first-ever friend, a new-media obsessed child named Podcast (Logan Kim).

Phoebe’s also too smart to ignore the multiple quakes that shake these rural environs several times a day, endearing her to Mr. Grooberson (Paul Rudd), the local summer school teacher. A few choice discoveries back at the dirt farm later, and Phoebe and Podcast find themselves hunting for ghosts. Trevor isn’t far behind, especially once he gets the Ectomobile running. But the metal-muncher they chase down an empty main street turns out to be an easy introduction to the horrors of the next world that lie just outside of town.

The younger Reitman plays fan service to his father’s work — despite its state of disrepair, the Ectomobile is given a veritable unveiling — but shades of the original show up in Ghostbusters: Afterlife in other aspects, particularly via the film’s score. For composer Rob Simonsen (The Way Back, The Front Runner), reimagining and expanding the world of Ghostbusters was just as much a matter of channeling the broader film world of the 1980s as it was about looking to Elmer Bernstein’s original score. We chatted with Simonsen about his favorite film references, fan service, and composing for visual effects ghosts.

How did you decide what to keep and what to leave behind in the score?

From the beginning, Jason Reitman was very clear that this should feel like an extension of the original. So we knew that we’d be working with material from the original and Elmer’s wonderful themes that he wrote. I think the question that we had for ourselves was how could we stretch that into new moods and new moments that don’t exist in the first? We knew that there was a lot of action in a style that wasn’t in the original, and we wanted it to feel like a mid-Eighties movie. In a way, this is an homage to the Eighties films that I grew up watching. So it was very much, let’s take the material from the original, let’s give an homage to the spirit of mid-Eighties films, and let’s do it with new material. It was about finding that balance. And I think it was very important to Jason to have the theme utilized in places that really helped the audience to feel like they’re in the universe of the original.

Any particular Eighties movies that you used as a reference?

Explorers, Gremlins, ET, of course, Back to the Future, of course. Those were really big films for me growing up. And they all have this enchanted quality, this wondrous, kind of inspiring tone to them. Those composers and those scores made a big imprint on me when I was young. It was really fun to go back and watch a lot of those movies again, and really have more time and energy to do more study of the way that those films were scored. It was just a very free time, the mid-Eighties. People dreamt really big.

In terms of the original Ghostbusters, was there any aspect of the score where you worked in some fan service?

There’s the ondes Martenot, which is a very early synthesizer-type of instrument that Elmer used extensively in a lot of his work. But specifically, it’s one of the characteristic sounds that he used in the original Ghostbusters, so we knew that we were going to have to use that. We sought out the woman who played it for the original, Cynthia Millar, and we had her play the ondes Martenot for us on the new score. So that was really cool, very satisfying. We knew we wanted a big orchestra. And we had a rule that we weren’t going to use any synthesizers that weren’t used in the original, so those were all sounds from a very infamous keyboard called the Yamaha DX7. Those were pretty big contributors to the sound of the original, as well as the very brash, apocalyptic brass that’s in the original. We worked very hard to try to get close to that same kind of brash sound. So many things have changed since that score was recorded, we did a lot of research and experimentation. But that’s what we were trying to get to.

Did the fact that most of the main characters were kids influence your scoring process?

For sure. We needed a sense of wonder and discovery for the kids and that was, I think really for me, such a touchstone for a lot of mid-Eighties films that record that feeling so well. And how do you play the Ghostbusters theme for kids and for emotional parts? The main Ghostbusters theme from the original is this kind of comedic, quirky, piano-driven, slightly jazzy, very New York sounding tune which was for a bunch of middle-aged men, comedians going and fighting ghosts. There’s inherent comedic value in that. And so trying to take that material and apply it to kids in rural America and emotional scenes, there was experimentation there. And it was cool. We got to reharmonize the melody of the original, put new chords underneath so it gave it a different flavor, and try to develop it in new ways. It was a really fun exercise.

How closely do you work with the visual effects team? Were you able to see any of the ghosts for whom you were composing?

When Covid hit, we got a lot more time to work on the film, so I had more visual shots done from VFX that showed what these things were looking like. But for a long time, they were very rudimentary versions. But I think that the vocalizations from the ghosts really helped me to understand what their character was. I know Jason worked really hard on nailing the voices of the Stay-Pufts and that was a tricky one to crack, musically — I think just tonally in general, to get them to be the right amount of menace and playful, these little chaotic terrorizing creatures that you like and they’re so cute — there are a lot of critter movies from the Eighties that ride that line, as well. Jason did a great job of explaining how they should feel, and that’s what I went on. I think it all worked out.

Featured image: The theatrical poster for Ghostbusters: Afterlife. Courtesy Sony Pictures