“Summer of Soul” Editor on Piecing Together the Nearly Forgotten Black Woodstock

For nearly half a century, videotapes documenting the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival gathered dust in the basement of a Bronxville home. Filmed by Hal Tuchin and his four-person camera crew, the trove included goosebump-inducing performances by Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Sly & the Family Stone, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Mahalia Jackson, Mavis Staples, B.B. King, the 5th Dimension, jazz drummer Max Roach and other masters of American music. Tuchin tried to package his work as “The Black Woodstock” but every TV network and film studio turned him down. Shortly before his death in 2017, Tuchin signed over his material to producers Robert Fyvolent and company. Fifty-two years after the fact, freshly restored festival highlights finally see the light of day in the documentary Summer of Soul (…Or: When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised).

Directed by drummer/producer/author Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, leader of The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon house band, Summer of Soul (opening July 2) condenses some 40 hours of footage, augmented with new interviews. into a 157-minute feature thanks to a substantial assist from Emmy-nominated editor Joshua L. Pearson. “We’ve seen so much Black pain in the news every day,” Pearson says. “Ahmir really wanted this film to be about Black joy. Of course, we had to include some Black pain, which makes the Black joy really sing.”

Speaking from his home in upstate New York, Pearson, who previously cut documentaries about Nina Simone and Keith Richards, talks about working with Questlove to tell the story of a pivotal year in Black culture.

Summer of Soul shows this closet piled high with reels of old videotape. How did you whittle down all that material?

The producer Joseph Patel and Questlove watched all the footage before I started on the job so they already had a road map of the songs they wanted to include. Ahmir was obsessed with the footage, playing it on loop on his computer all day long. He became so intimate with all the songs, everything was ingested and laid out for me, alphabetically by artist and chronologically in terms of how each weekend actually played out.

In addition to these astonishing performances, the film also includes new interviews with people like Chris Rock, Al Sharpton, and Lin-Manuel Miranda who help put this festival in historical context. How did you weave all these elements together?

The tricky thing is that we didn’t just want back-to-back music so we included the socio-political background for our between-song stuff. It’s a delicate balance. How long can you go between songs before you want to get back to the music? How much can you have dialogue step on a song? A few songs played all the way through but for many of the others, I had to find places to cut ’em down while still creating the illusion that you’re getting the full song.

How did you structure the sequence of performances?

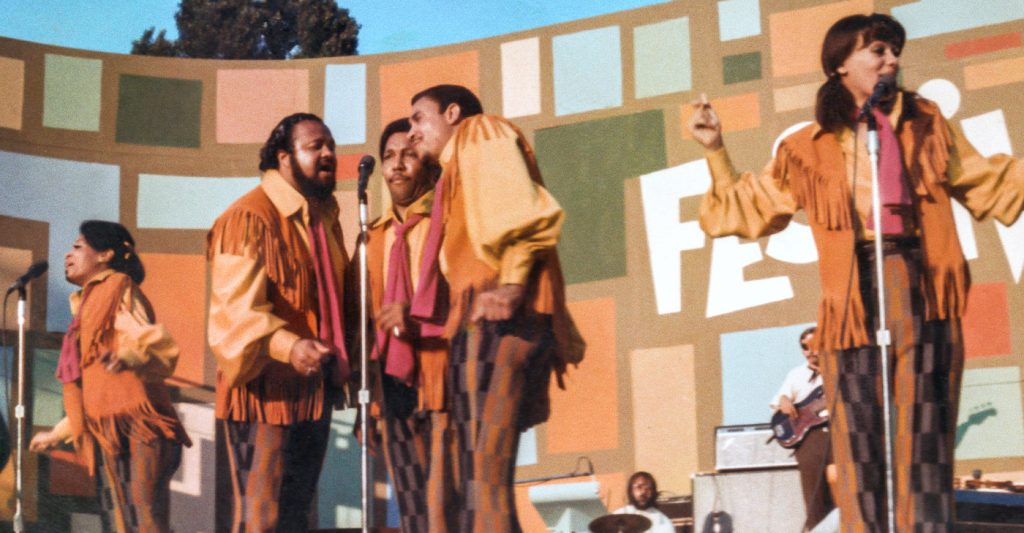

We were trying to show that 1969 was a very pivotal year for both Black music and also Black culture. Questlove interviews the journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault about how she got the New York Times to use the word Black for the first time instead of Negro. Musically, it’s such a transitional time, which made the Gladys Knight and the Pips performance interesting. They were still doing their Motown thing trying to be clean and polite and dressed perfectly but then they give the Black Power salute as they walk off stage. From there you go to Sly Stone. That guy who was in the audience back in 1969, Darryl Lewis, said it very well, “We were suit and tie guys, but then we saw Sly Stone and we weren’t suit and tie guys anymore.” In 1969 you had these incredibly varied types of Black music together in one festival.

That variety sustains excitement because it’s not just the same genre over and over.

We start with a mélange of styles, the Fifth Dimension and gospel with the Edward Hawkins singers. Then we go to Motown which comes out of gospel, and the sort of future funk of Sly Stone. After that, all hell breaks loose with this insane music from Avant-garde guitar player Sonny Sharrock making this incredible skronk noise and Max Roach doing free jazz drum solos and [singer] Abbey Lincoln. The film has an arc showing a progression from the traditional to the Avant-garde.

The emcee/promoter Tony Lawrence played a critical role in making the festival happen and he’s every bit as colorful as the musicians on stage. Had you ever heard of him before this film?

No, and in fact, he’s a bit of a mystery because, after the concerts, no one ever heard of him again. The producers tried to find information about Tony but or family members related to him. Unfortunately he kind of drops off the face of the map.

How did you go about organizing the material?

Questlove would come by early to meet because he had to go shoot the Jimmy Fallon show every day. We’d put cards up on the wall, maybe change the order of things, but Ahmir was very insistent about certain performances. Being a drummer himself, he knew he wanted to start the movie with this amazing Steve Wonder drum solo, which is something not many people have seen. And we had to use Sly Stone’s Sing a Simple Song. because there’s that incredible drum breakdown in the middle. The producer told me that section is what made Ahmir want to be a drummer, so he was sentimentally attached to Sing a Simple Song.

The Woodstock festival took place 100 miles north of Harlem the same summer and garnered massive attention while this equally wondrous showcase attracted hardly any media coverage. From a filmmaking standpoint, how does your project differ from the Woodstock documentary?

The Woodstock film is very immersive because they had 15 famous cameramen wandering around with sixteen-millimeter cameras getting all this great footage making you feel like you were right there in the crowd.

By necessity, your edit took a different approach?

They didn’t have money for film stock and only had four cameras on stage, with just one of them pointing out at the audience. Since we couldn’t do the immersive thing, Summer of Soul is more about the audience having the privilege of looking at this incredible artifact. The musicians’ sets were really well shot so you experience the excitement of their performances but at the same, it’s like you’re in a museum looking at a beautiful painting or piece of bronze jewelry from [ancient] Greece. And part of that feeling comes from the way we frame the movie, starting off with tape hiss as Ahmir asks someone who was there: “What do you remember about this concert?” We’re setting it up to feel like “Oh my god I’m watching something precious that hasn’t been seen in 50 years.”

Now that these performances from 1969 are finally seeing the light of day, how do you see Summer of Soul landing with audiences in the summer of 2021

Of course it’s a shame that this footage sat in a box in a basement for 50 years, but after percolating all this time, it’s like finding treasure now. Last summer was so horrendous, with George Floyd and the pandemic, somewhat parallel to 1968, which was an especially hard year for Black people with the killing of Martin Luther King. So 1969 was a summer of venting and release and I think this summer is going to be like that too. You feel good after you watch our movie.

Have you seen Summer of Soul with an audience?

I watched a live screening last week at Mount Morris Park in Harlem where the original festival took place. It was kind of mind-blowing. Everyone clapped and cheered after every song. During the gospel section, people around me were testifying, holding their hands up in the air. And it was weird because they’d built this backdrop for the stage behind the screen that was just like the original backdrop made of multicolored blocks that you see in the film. I felt like I’d fallen into some kind of wormhole, with the live event from 1969 being transmitted through time in the same spot. Trippy is the only word I can think of to describe it.

Featured image: Nina Simone performs at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969, featured in the documentary SUMMER OF SOUL. Photo Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures. © 2021 20th Century Studios All Rights Reserved