How “The Unholy” Visual Effects Team Created Biblical Scares During Scary Times

“In the early innings, as the pandemic was ramping up, it was like looking out at the ocean and you see a storm coming, and you’re not sure you can get to shore before the storm gets there.” That’s an observation that might describe most of the past year; certainly, it’s politics, work and school life, and of course healthcare delivery. In this case, it also applies to the almost all-virtual workaround to finish the recent Screen Gems horror release The Unholy, a project started in those more innocent times when people stood closer than six feet together, including on film sets, went around unmasked, and sometimes even breathed on each other.

The roiling storm metaphor was a suitably visual one, belonging to Robert Grasmere, who serves as creative supervisor for Culver City-based visual effects house Temperimental, where he works with Raoul Yorke Bolognini, company founder and executive producer, who was also the VFX producer for the film.

Unholy’s story concerns various layers of reality and history being finally revealed, or unleashed, when a seeming visit from the Virgin Mary sparks a series of miracles in a small Massachusetts town; a mute, hearing-impaired girl suddenly talks (and becomes the spectral visitor’s main spokesperson), those confined to wheelchairs can walk, and more. Jeffrey Dean Morgan’s washed-up news photographer initially refuses to believe, then realizes there is indeed something beyond normal human understanding afoot; a thing that may extract a harrowing price for its seeming beneficence.

The film was the first directorial effort from writer Evan Spiliotopoulos, who also adapted the script from James Herbert’s book Shrine. They’d already planned for what was assumed to be a “traditional” amount of FX work for a genre production, especially one with an increasing number of otherworldly visits as the story progresses.

There was going to be a mix of location work, in the Lovecraftian countryside of the Bay State, along with scenes that were going to be done on set, but that incoming storm changed all that. “Some scenes were half done,” Grasmere says, “some not at all. We didn’t get to a lot of crowd stuff,” including scenes toward the end where they “needed crowds to run together, to panic together.”

Getting shut down ten days before they’d planned to wrap, they had to “learn what the rules of engagement were going to be,” if the production was going to be salvaged, Grasmere recounts. Bolognini adds “that was the challenge right there. We went in thinking we were doing traditional effects,” and suddenly, they were doing something wholly unprecedented.

“Raoul and the Temperimental team were all crunching numbers, and coming up with storyboards,” Grasmere said, when the production “came back with information that some actors weren’t going to be able to travel.”

In some cases, the actors who were supporting Morgan’s reporter, or Cricket Brown’s darkly-channeling prophet, couldn’t even be on the same continent: Cary Elwes, William Sadler, and Diogo Morgado all play clerics caught up in benefiting from, or seeking to disprove, the apparent revelations.

Normally in an effects shot, “you do two or three panels that you composite together,” Grasmere notes, but now, Bolognini adds, there were “at least thirty layers.”

All that extra layering, Grasmere explains, came because “we had to shoot the two lead actors separate, the priest separate, (the) crowd had to be shot six feet apart.”

In other words, crowd scenes are usually extended, digitally, when a small crowd is amplified, or replicated, to fill a room, a street, a stadium, etc. Usually, this comes from replicating an initial shot, section, or grouping of people. And while the process was theoretically the same here, it had to be broken down much more, because no one could stand next to each other.

“We’d put up green screens,” Grasmere says, and place background actors in “seat 1, seat 6, seat 12, then we’d move them over and shoot them in seat 2, seat 7,” and, to quote Yul Brenner in The King and I, “et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.”

“Shots that normally would not have had visual effects,” Grasmere observes, were now chockablock with them.

“Every single camera angle that we shot, had to be recorded,” Grasmere adds, and not just for plates where originally planned effects were going to go. “For every single camera position, we had to record the data for where each actor was, then another unit came in a week later and recreated all the angles.” This was done so that another actor could move around the set, and interact with the earlier one. “It was a tour de force of planning.”

There were other forces that came to the aid of Temperimental in allowing the production to finish with nearly seamless, spliced-together visuals. “We had two units running day and night,” Bolognini says. “That meant bringing in some additional (VFX) supervisors to help Robert.” Prague’s UPP, a post-production house, offered crucial assistance.

There was also a shout-out to cinematographer Craig Wrobleski. “He was really good about working within the storyboards that were created,” Grasmere says. Still, when they found themselves shooting remotely in Portgual, where Morgado was, they needed a counterpart for Wrobleski, too, along with another VFX supervisor.

“Evan, the director and I, joined from America,” Grasmere recounts, “and we had a live link to the stage.” And this wasn’t over Zoom, but a customized, far more hi-def connection.

This allowed Grasmere to notice nuances, and make suggestions. “You need a little more light on the right-hand side of the green screen,” Grasmere recalls. “Evan and I basically shot through the entire (sequence). It was a fascinating process really, to supervise the visual effects remotely.”

But as more robust networks get set up, remote work may become more and more a regular part of movie-making, whether herd immunity is reached near term, or not. “Visual effects is ahead of the game in terms of remote work,” Grasmere states. “Raoul started this company not to be a brick and mortar place; he was ready to go with the Temperimental model. When other companies were struggling with how to get their artists to work from home, Raoul was using (partner) companies that were already set up that way.”

“We were already good to go,” Bolognini says. Even in the midst of an unholy mess of a pandemic.

The Unholy is playing in theaters now.

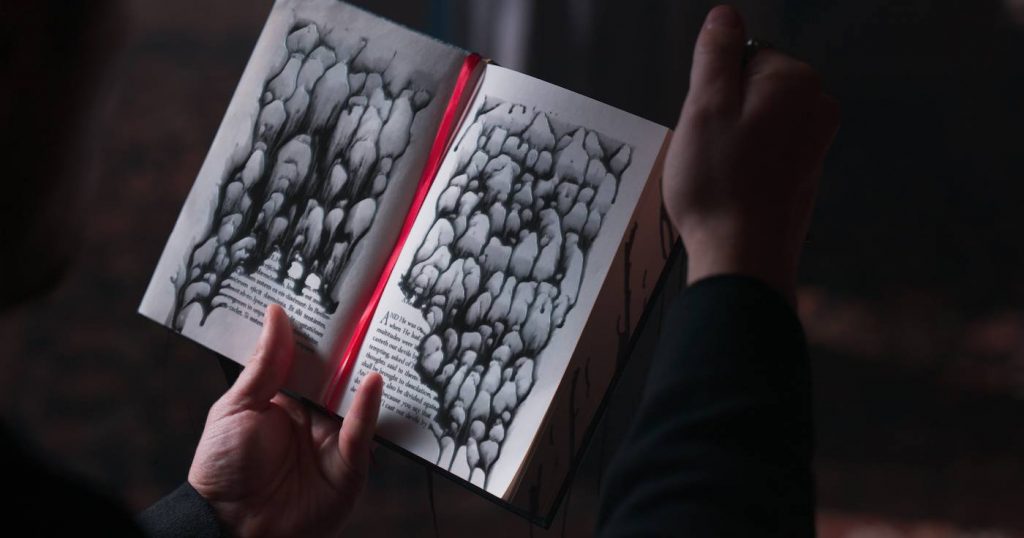

Featured image: VFX shot from “The Unholy.” Courtesy Temprimental/Screen Gems