Director Shaka King Breaks Down the Magic Trick Behind “Judas and the Black Messiah”

Judas and the Black Messiah opened last month and quickly galvanized moviegoers with its fact-based story about Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, whose betrayal by an FBI informant led to his 1969 death by gunfire at age 21 while sleeping in his own Chicago apartment. The film racked up six Oscar nominations including Best Picture. Director Shaka King earned a nomination for co-writing the screenplay and steered co-stars Daniel Kaluuya and Lakeith Stanfield to their own Oscar nods in the Best Supporting Actor category.

Judas and the Black Messiah‘s success is all the more striking given that King previously specialized in comedy, including his 2013 indie feature Newlyweeds and HBO’s blissful stoner series High Maintenance. But his ability to design Judas as a populist thriller reveals a shrewd grasp of Hollywood basics. “It was a magic trick to pull off,” King says. “Telling a story about a Black Marxist who got shot in the head by the FBI when he was 21 years old and making that a popcorn movie—can we do that? And we did!”

Raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant by school teacher parents, educated at Vassar College, and mentored by Spike Lee at NYU, King embarked on Judas nearly five years ago when comedy duo Kenny and Keith Lucas pitched him a “two-hander” premise centered on a car thief-turned FBI plant and his charismatic target. After writing a finished script with first-timer Will Berson, King enlisted heavyweight producers Ryan Coogler and Charles D. King (Mudbound, Harriet, Just Mercy), secured co-financing from Warner Bros., and filmed in Cleveland as a stand-in for Chicago during the fall of 2019.

Speaking from his home in Brooklyn, King explains how Eddie Murphy’s voice impacted Kaluuya’s rhetoric, praises the power of specificity, and delves into the darkest day on set during the making of Judas and the Black Messiah.

Congratulations on all this Oscar recognition. Starting with your nominated screenplay, it was kind of a stroke of genius to have the “bad guy”—FBI informant Bill O’Neal—front and center rather than the obvious hero Fred Hampton. How did you arrive at that idea?

It was baked into the script when the Lucas Brothers reached out to me saying they wanted to make a movie about Fred Hampton and Bill O’Neal that was like The Departed but set in the world of [FBI Counter Intelligence Program] COINTELPRO. The reason for me getting excited about the story’s potential is that I recognized it as a way of getting a movie about Fred Hampton out to the most amount of people by couching it in genre. If you look at the first trailer we put out, people who might have been unaware of the Black Panther politics still wanted to see this movie because it looked exciting and thrilling and dramatic and action-packed.

So you couch the political message within this time-honored crime genre, like The Departed. Except here, undercover guy is bad and the target, Fred Hampton is the good guy.

It’s subversion on multiple levels. First, we’re couching this political movie within a crime genre, but then we’re also flipping the genre on its head by having the fox in the hen house. It changes the way that you engage with the protagonist. You’re not rooting for O’Neal [to succeed]. You’re rooting for him to have a change of heart. You’re rooting for him to do the right thing. It’s very hard to navigate emotionally because you’re leaning on tropes and subverting tropes at the same time and as a result, you’re confusing people.

Lakeith Stanfield, whom you directed earlier in your short film LaZercism, does a very convincing job of portraying the informant O’Neal as a bundle of nerves. Getting into character like that must have been a grueling experience for him.

In his heart, it was hard for Lakeith not to judge O’Neal. In writing the script, my co-writer Will Berson and I tried to give Lakeith a road map to do that, because as writers we went through the same process. In the first several drafts, we were labeling O’Neal as a sociopath until we realized we needed to get more interior with this guy. In doing so, we got something on the page that gave Lakeith a chance to infuse his own level of empathy into the character. Throughout the shoot, he essentially needed to click himself into the position of a 17-year-old who has to make these decisions.

Lakeith as jittery O’Neal contrasts with Daniel Kaluuya’s performance as this hyper-confident 20-year-old Chicago activist. Daniel’s from England and he’s a few years older than Hampton. How did you arrive at the idea that Daniel Kaluuya should play Fred Hampton?

It was just an intuitive decision, same with Lakeith, same with Dominique [Fishback] as Fred’s wife Deborah, same with Jesse Plemons as the FBI agent. I wrote the roles for these actors.

You’d seen Daniel in Get Out?

First thing I saw him in was Sicario and then Get Out and also Black Panther. From those three films, I could just tell he was a really good actor.

Daniel brings this ferocious eloquence to his portrayal of Fred Hampton, especially when he’s giving speeches. How did you prepare him for the demands of this role?

A year before shooting, Daniel and I got together in L.A. for four days and started to play with the dialect. I had some influences I wanted him to listen to that were all over the place.

For example?

Bernie Mac, [comedian] Robin Harris, Eddie Murphy—specifically a voice he does in Eddie Murphy Raw—Busta Rhymes, Fred Hampton Junior, and obviously Fred Hampton himself. Like I say, it was all over the place. After we did that, Daniel went off on his own and worked with Audrey LeCrone, our incredible dialect coach. They did the heavy lifting. Daniel also studied with an opera instructor who taught him to essentially sing Fred’s words from his diaphragm so he could do these big speeches without blowing his voice out.

The film looks great, with this rich, almost painterly color palette. Your cinematography Sean Bobbitt earned an Oscar nomination for his work on Judas. What did you guys reference in terms of shaping the visuals?

My friend Akin McKenzie, a production designer, sent me about 300 photographs of the west side of Chicago from 1967 to 73. When I showed this stash of images to Sean we immediately agreed we wanted to replicate the Kodachrome look from those photographs. Once our production designer Sam Lisenco came on board, he found these perfect locations for us in Cleveland. That city is a time warp in a lot of ways. So it was really about trying to create a movie that felt of that era but where the cinematic language was contemporary enough that today’s viewers, especially young viewers, wouldn’t feel alienated from it.

The Black Panther Party generated a powerful iconography in the sixties and seventies. In going beyond that popular imagery, did you want Judas to deepen people’s understanding of the Black Panthers?

The primary goal was to correct the record because much misinformation has been put forth about the Black Panthers: that they were terrorists, that they were racists. In this film, we showed the community organizing, we showed survival programs in action, we showed Black Panthers in the classroom, we showed that they were thinkers, philosophers, and doers. But then you use the word icon, which is exactly what they were. To be an icon is to be two dimensional. When you make a movie about an icon, it’s your job to create the third and fourth dimensions. So my other intention was to show that yes, Fred Hampton was a gifted orator and fearless leader, but also, there was this woman he was in love with, this child he wanted to have. We wanted to show Fred Hampton as a man who makes a difficult choice, so viewers get a real sense of this incredible sacrifice.

Your re-creation of the night-time shoot-out when Fred Hampton gets killed in his own bed serves as the film’s bleak climax. That must have been a dark day on set?

The truth of the matter is that those sequences were so technically focused, so stunt-heavy, so ballistic heavy, that there’s a certain level of emotional distance. Really, the heaviest day of the shoot happened when Keith has to drug Fred [to sedate him before the FBI attack]. That was heavy for everyone because it was the 50th anniversary of the assassination. Heavy for Daniel because it was toward the end of the shoot. Heavy for Dominique, saying goodbye to someone she’d grown to love as a person, Daniel, and in character, to her husband Fred. But nobody was having a worse day than Lakeith.

Why is that?

In a very Method kind of way, Lakeith was digging into some personal trauma to go through with this act. He inhabited the character to such a degree that he felt like he was really poisoning this person in real life. He woke up that morning crying, and all day he was crying. In that scene where he drugs Daniel, ONeal’s supposed to be on the verge of tears. But Lakeith wasn’t on the verge. He was actually crying. I told him, ‘You gotta stop. I can’t use this. Your cover is blown if you’re crying before you do it.’ Once I was finally able to get him to pull it back just a bit, he was in the perfect place, and that’s what you see in the movie.

Before making Judas, you mainly worked on comedic stuff. How did your expertise in comedy help you direct this very somber drama?

Well, for me comedy is all about specificity. That’s what makes me laugh. I think of Kings of Comedy when Cedric the Entertainer does a joke about how [car] mechanics talk to you with a cigarette in their mouth the entire time. And then he shows it. And it’s that specificity that makes the joke play. So for me, drama is just about finding that specificity.

On a lot of levels, Judas and the Black Messiah feels very timely. How do you see Fred Hampton’s message of empowerment landing in 2021?

Essentially, the same ills remain. Kids are still hungry, there are still predatory landlords, prisons are still filled with black and brown folks that shouldn’t be there, the rich still getting richer, poor getting poorer, people still not getting access to decent health care, workers are still being exploited in the nation and worldwide. Fred Hampton and the Black Panthers were looking to address problems that are still applicable to society today.

You started working on Judas nearly five years ago. It must be gratifying to see the impact it’s having.

Absolutely it’s been gratifying to see audiences react to this movie so well, and also gratifying to see that the people who lived through this experience were really pleased. We’d been in dialogue with Fred Hampton’s son for a year and a half before cameras rolled, trying to get him on board as a consultant. He was on set every day. Same with his widow Deborah Johnson. It took a year and a half to get to know them. So that was the ultimate gratification.

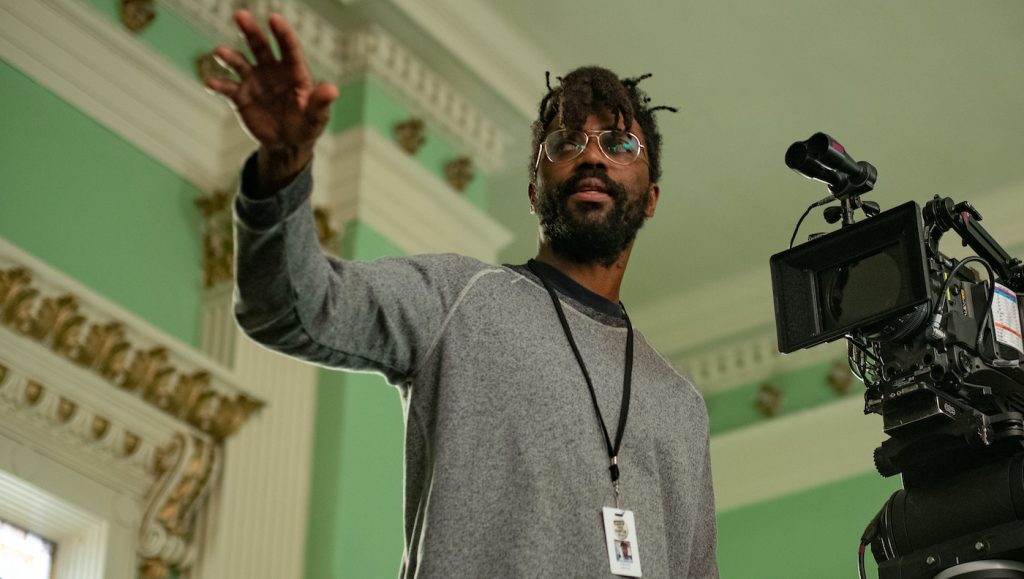

Featured image: Caption: (L-r) Director SHAKA KING and DANIEL KALUUYA on the set of Warner Bros. Pictures’ “JUDAS AND THE BLACK MESSIAH,” a Warner Bros. Pictures release. Photo Credit: Glen Wilson