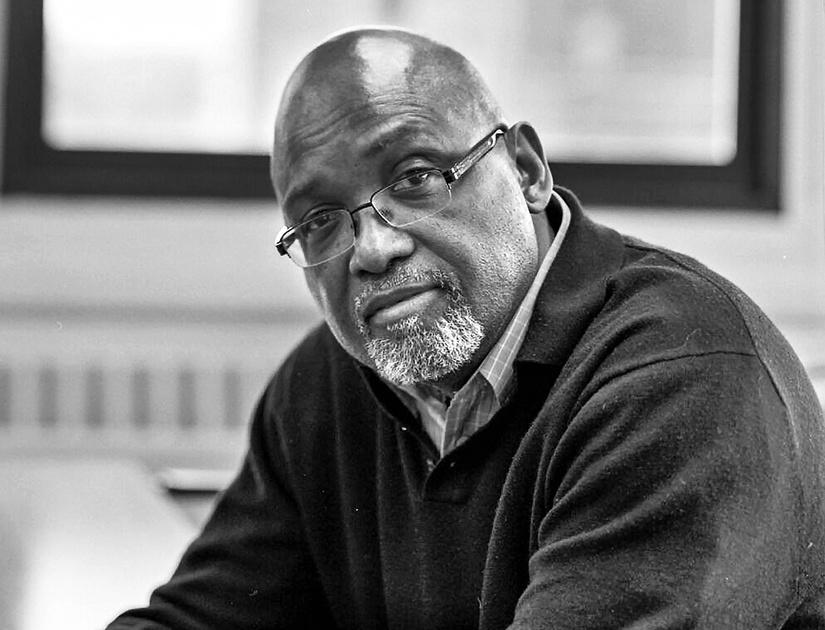

Director Sam Pollard on the Legacy of Black Art in his New HBO Documentary

HBO viewers likely know the names Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, the artists who painted Barack and Michelle Obamas’ respective official portraits. The network’s latest documentary, Black Art: In the Absence of Light, an expansive, joyous 90-minute look at art history directed by Sam Pollard (MLK/FBI, Atlanta Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children) and executive produced by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., lets viewers in on their processes, as well as that of many of their living art world contemporaries, including Sanford Biggers, Faith Ringgold, Kerry James Marshall, and Kara Walker.

More than an exploration of blue-chip artists working today, however, Black Art delves into the history of Black artists in America past and present, contextualizing the processes and output of contemporary creatives with insights into the collecting practices of major institutions, the importance of Black collectors and art spaces, and the impact of shows like “Two Centuries of Black American Art.” Framed around that groundbreaking 1976 exhibit, curated by the late artist and scholar David Driskell, Pollard interviews the erudite Driskell and an array of working artists, art historians, and collectors like Swizz Beatz to reveal a deeply interconnected two-hundred-year legacy of African-American art.

The documentary also addresses the widely criticized 1969 Metropolitan Museum of Art show “Harlem on My Mind” (put together by a white curator and which, aside from photographs, hardly featured any Black artists or, strangely, really any art at all), contrasting it with the lasting success of “Two Centuries” (even if some of the critics didn’t get it at the time) as well as that of “Black Male,” curated at the Whitney in 1994 by the Studio Museum’s executive director Thelma Golden, who is also featured in Black Art. We had the chance to speak with Pollard about bringing such wide-ranging representatives of the art world together, how he chose to frame the documentary, and what he hopes viewers, whether they’re interested in the art world or not, will take away from Black Art.

What first brought you to this subject matter?

It was HBO. Henry Louis Gates, one of the executive producers, had initiated the idea with HBO before I was involved. Then he brought in Thelma Golden, who is, as you know, the executive director of the Studio Museum. I guess they were looking for a director who they thought might be a good fit, and they tapped me on the shoulder. Luckily and fortunately for me and the project, I happen to know a little bit about Black artists. I felt it was something I could bring something to.

Was that familiarity more rooted in the contemporary art scene or artists from farther back in history?

I’ve always been fascinated with African-American artists, ever since I was a teenager. I was pretty fortunate when I was in my 20s or early 30s, I happened to spend some time with Albert Murray, the wonderful writer, and he was doing the forward for a book of artwork for Romare Bearden. There was a little restaurant right next door to the Whitney and he invited me to have this meeting with him and Romare Bearden. I think that was the only time I ever met Romare Bearden. I was familiar with him, Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence, Sanford Biggers. I was familiar with a lot of those artists from that period.

How did you seek out and choose younger working artists featured?

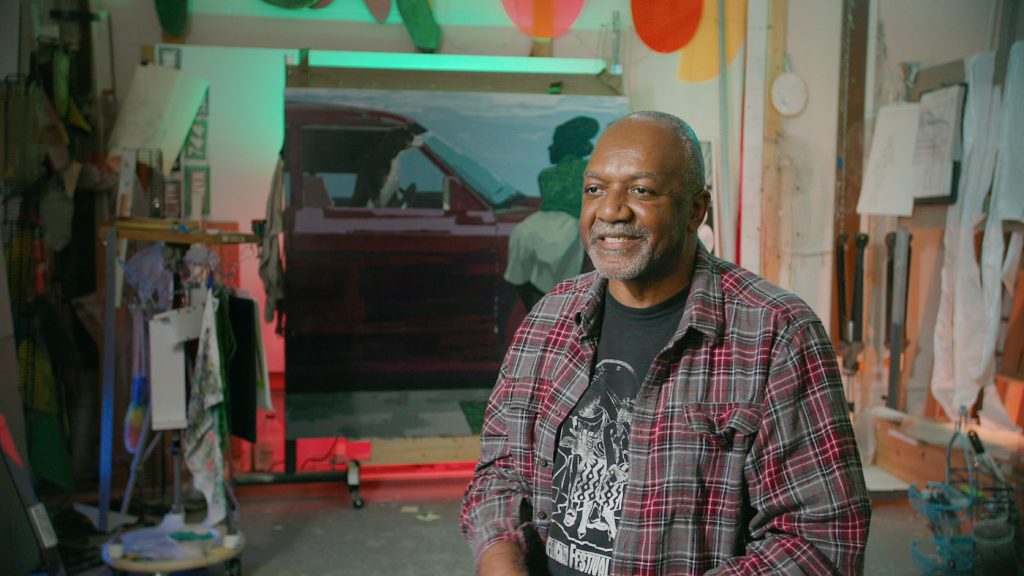

Well, you know, when you’re doing a film like this, you’re going to have to leave some people out and you’re going to have to find people where you find some connection to their work. So there were some artists I was immediately inspired by, and intrigued by their work and their process. As a filmmaker, I love the idea of process—how you come to create what you create. That led me to Theaster Gates, not only because he’s an artist but because he’s an entrepreneur. I reached out to Amy Sherald because I loved what she had done with the Michelle Obama portrait and I loved her other work. I reached out to Kara Walker because she’s such a lightning rod, and I love the fact that she’s so controversial. I reached out to Carrie Mae Weems who’s just an old friend and whom I respect tremendously. And Fred Wilson, whose work I didn’t know, but I was very intrigued by his going into museum’s libraries and finding other material to create these exhibits. There are always some people you leave out, but I felt like the artists we selected spoke to contemporary African-American art today, but also many of them understood the legacy of David Driskell’s “Two Centuries of Black American Art,” which the film is framed around.

Was it the plan from the start to center the film on that groundbreaking show?

That was really Thelma Golden’s idea, to build the film around David Driskell’s “Two Centuries of Black American Art,” which opened at the Los Angeles County Museum in 1976. I originally thought that we wanted to build the documentary around Thelma’s “Black Male” exhibit that was at the Whitney in 1994, but she felt we should go broader and wider, and that’s when she mentioned Driskell. She introduced me to David and I spent some time with him. I went up to his apartment one night and we had dinner and we talked about the inspiration for the exhibit, the artists he put into it, and his own work as an artist. I was so engaged and taken by him, I realized Thelma hit it right on the head. This was the perfect person and perfect exhibit to frame the whole film.

We were so sorry to learn David Driskell had passed. How was interviewing him?

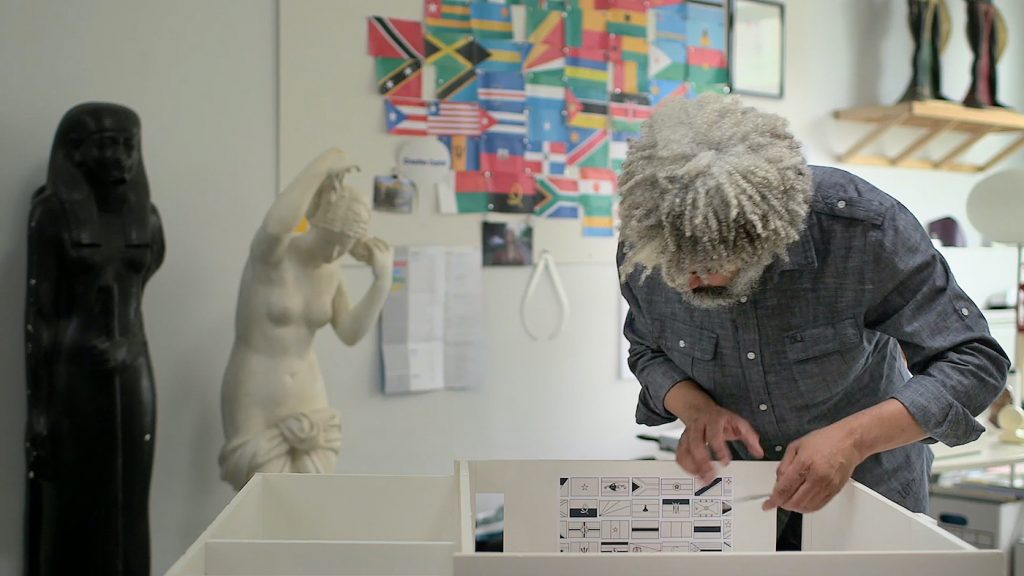

It was wonderful. We went up to his house in Maine in the summer of 2019 and spent two glorious days with him, watching him work in his studio, doing a long interview about his evolution as an artist and a curator. Then we spent some time in his home, where he had a wonderful collection of African-American art that he’d been building for years.

In general, did you mostly shoot the film’s subjects in their own homes and studios?

Except for the historians and art scholars, we shot people like Sarah Lewis, Mary Schmidt Campbell, and Richard Powell in a space that we found. But all of the artists, from Amy to Jordan Casteel to Kerry James Marshall, we shot them in their space. I think the only artist whose space we didn’t shoot in was Carrie Mae Weems because she lives upstate.

It’s easy for films about the contemporary art world to veer into hot air or pretentious territory, which Black Art completely avoids. Were there any art world tropes you tried to steer clear from?

Anytime I interview someone, I’m just trying to connect as one human being to another human being. I’m trying to understand why they do what they do, what inspired them to become an artist, what’s their process. That’s what I try to do. I’m not trying to say, let’s talk about the art world from this perspective. I’m looking at them as an individual who has come to this craft because they felt some kind of inspiration, they felt they had something to say, and this was the medium they wanted to say it in. That’s always my approach, one-on-one conversations that are as human as possible.

Do you personally have a favorite artist among those featured? And are you a collector yourself?

We collect a little bit. We have some Basquiats in the house here and some other artists we collect. I don’t think there’s one particular favorite, for me. They all have something I find unique. I have tremendous respect for creative people. I have tremendous respect for the process to create. In a way, for me, it was like a treasure to be able to spend a day or two in Amy Sherald’s studio, watching her create. It was wonderful to watch Theaster go from his quarry to inside his wood factory, to watch him work with clay. That’s fantastic to me. To be able to spend time with Kara Walker. I think Kara Walker’s one of the great artists, myself. I love the fact that she challenges the perspective of the African-American experience, and the fact there’s always so much debate around her work. So to me, it’s one of these jobs where I could have done it for free.

How did you find collectors to interview?

We had a great associate producer, Chelsea Ademunwi, and she understood the art world really well. When we started talking about collectors, she mentioned some people that I had never heard of, like Bernard Lumpkin. She might have mentioned Swizz, which I thought was really hip, to have this young hip hop producer type, married to Alicia Keys, who’s so into art. It was just really doing some deep research for people we thought could talk about the art from the perspective of understanding the artists. That’s why we were able to reach out to Bernard and Swizz Beatz, who was hard to get—it wasn’t like he immediately said yes. We had to do a little bit of a dance, but I’m glad he came through.

Is there was one thing you’d want viewers who aren’t “into” art or perhaps aren’t already hugely knowledgeable about art history to take away from the documentary?

Absolutely. I didn’t know much about any African-American artists until I got into my teens, so this is an opportunity for young people, or all people, to know that there were a fabulous group of 20th-century African-American artists, from [Elizabeth] Catlett to Selma Burke to Romare [Bearden] to Richard Mayhew, who’s in this film, and that they left a lasting legacy for artists like Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald. And you want people to go into museums, either through the internet or physically, to be able to look at some of this artwork and see it in these different museums. In all honesty, as a young man, before I started to really delve into this world in my teens, the artists I was familiar with were Picasso, Michelangelo, Van Gogh—and you know and I know that there are so many other wonderful artists, and there’s a group of fantastic African-American artists past and present that people should be aware of.

Black Art: In the Absence of Light premieres on February 9 at 9.pm. EST on HBO.