Emmy-Nominated Production Designer Jason Sherwood on Designing the Oscars

At 30 years old, Emmy-winning production designer Jason Sherwood became the youngest person to ever design the Oscars for this past year’s historic ceremony. Sherwood, already a talented theater designer, nabbed his first Emmy just last year for the design of Rent Live (which was also his first foray into major TV production).

For this year’s Oscars, Sherwood and his collaborator and fellow nominee, art director Alana Billingsley, teamed up to design what turned out to be a historic ceremony. The pair first met at last year’s Emmy Awards, on the dance floor, after he won for Rent Live. “And then three months we talk all day, every day, for months and months and months,” Sherwood says. “She’s become a dear friend and an incredible collaborator, so we’re very lucky in that sense. It’s nice to share this with her.”

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length. Sherwood was also kind enough to share some visuals with us via Zoom, the video of which we’ll be publishing later this week.

How did the Oscars compare in terms of the sheer amount of work you had to do with the equally massive undertaking of Rent Live?

It’s such a different project than something like Rent. Rent is a scripted musical, we knew the outline of what it was going to be, so you got to plan ahead for everything because you knew what the story was, beat-to-beat. The Oscars is such a reactive thing, it has to respond to the vision and hopes of the team, which in this case was to create something that felt visually different from Oscars past. But then also, you have to somehow respond to the landscape of films in a given year. The greatest primary difference is that Rent is all grunge and texture and 90s New York and the Oscars is Hollywood’s most glamorous night [laughs]. To get to be a part of both in such a short period of time, as two tent-pole projects in my professional life, is kind of a hilarious contrast.

You start designing the show before the nominations come out. How much do you have to pivot when you finally know who’s being nominated for what?

When the nominations come out, we respond to which songs and which films [were nominated] and build performances and moments within the show around that. It’s this ever-evolving thing, and you have to be reactive and be on your toes. The biggest pivot is that, with two or three weeks between nominations and show day, we find out that we’ll have these five songs, and we’re putting all five on the air with performances. And all five are megawatt stars—Elton John, Idina Menzel, Cynthia Erivo, Randy Newman, Chrissy Metz—it’s a huge slate of artists with people around them who are very creative and want to make the performances as special as they can be. So we get on the phone with them immediately and start discussing ideas, what might excite us, what might excite them, and then we have to design and execute those ideas in like ten days.

And that wasn’t even the entire musical slate!

Getting those five music performances together, plus an opening number with Janelle Monáe, a secret performance by Eminem, and a Best Original Score montage musical compilation all wrangled together is a ton of work.

When you’re talking to the artists, do they get a say about what elements they want to see on stage?

It’s definitely a collaboration. At that point in the process a lot of the primary set, those swirling shapes, are built or being installed in the theater, so there are confines to what’s able to happen. But then we work to make magic happen. Sometimes the artist comes with a very specific idea and exactly what they’d like it to be and we all work to make that happen. The idea of all the different Elsas all over the world singing together, that was our producer Lynette Howell Taylor’s idea, that was sort of her baby and she made that happen. The sunglasses that Elton John performed in front of, that was an idea that came from us. Cynthia Erivo had very specific thoughts about her styling and the color palette and what she wanted to see, so we were all able to collaborate and bring those things together. I think, by and large, the goal is to say, ‘What excites you and what excites us, and what’s possible,’ and then make that happen. The rigorous part is that it all has to happen in a matter of hours. [Laughs].

Give us a sense of the number of people it takes to design and build the ceremony?

The way I explain the job is we’re like architects for the stage. As the production designer, I’m like the lead architect on a project. Here’s the vision, here’s the drawing, here’s the client interfacing. Then Alana, as our art director, is a project coordinator meets co-architect meets lead draftsperson. She also creates the drawings that are sent out for pricing. Then we have a team of several support people. And then we have vendors who actually build everything. Those are scenic shops and fabricators and engineers and scenic artists and textile experts, and they build things out of steel and break them apart into pieces and rig them with motors. It’s a really complicated process. Then there’s a whole team of people that install all of this into the theater, like people building a house. So it’s dozens and dozens of people because so many hands go into actually making these things come to be.

Walk us through the process of creating the stage.

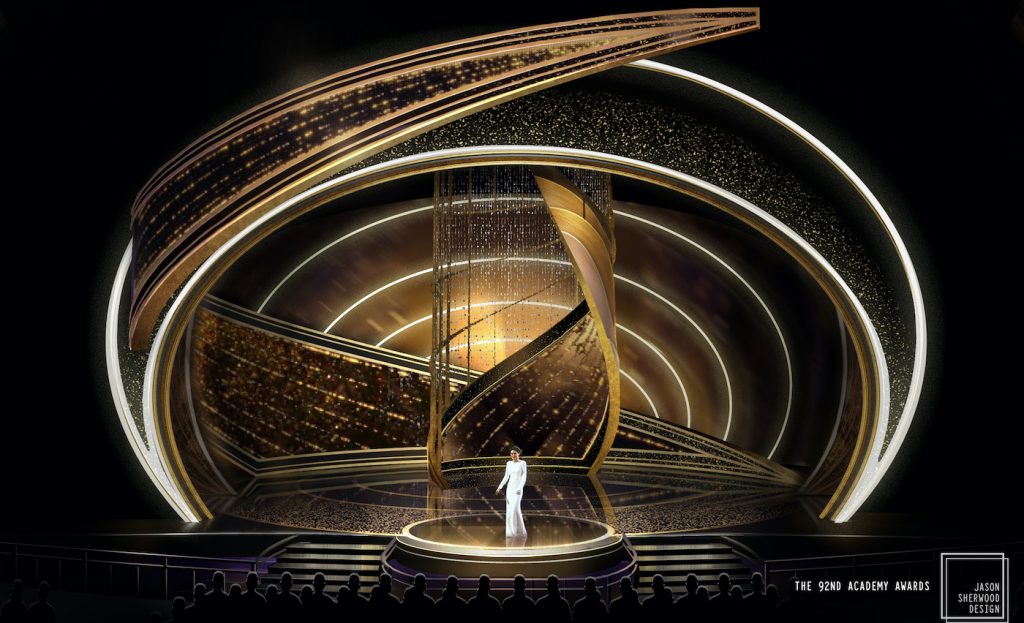

The easiest way to explain the job is through three of four images of the process. This is an image I made in those three days between hired to do the show and making the first presentation. This is the first picture the team saw of what my idea of what the set could be. It’s a very rough image.

Then we spent some time and we developed it a bit more. We played around with the shape and played around with our understanding of what the design might be or what it might do, and we developed a model of the show in motion to show how the whole thing could operate, could move, could change. You see things flying away, a close-up, how the whole thing might change, or how we might use the screen. Eventually, we land on where the whole thing is going and we develop a series of finished images. This is almost photo-realistic to what the show ended up looking like.

And while we’re doing this, concurrently the whole thing is being made, which is the most exciting part of the entire process. You see me standing in front of the bare skeleton of that cyclone, which is 36-feet tall and weighs thousands and thousands of pounds. It almost didn’t make it into real life because it was such a complicated piece of machinery. What’s insane about this picture is the show was on February 9, and this picture was taken on January 15. That’s how tight the window was, and how unfinished it was.

It’s just an unbelievable amount of work in such a short period of time.

The process is very rewarding. You have the left-side brain of creativity and the right-side brain of, okay, now we have to figure this out. We have to work with people to engineer this and make it happen, we have to consider the weights of things, where the lights go and how the camera can film this and the resolution of screens. It goes on and on and on. You have to maintain the idea that you had and try to make it look effortless and beautiful, while also contending with all of the logistical parameters of what it takes to pull it all off.

Where do you see the near-term for you considering the pandemic has shuttered so many productions and changed so much of how we think about work in general, and your kind of work specifically?

I’ve been inspired by folks who have been able to create genuinely entertaining or genuinely exciting opportunities in the digital space. Personally, it’s been an interesting time to reflect on the state of the industry I’m a part of, the state of the world, what we’ve been doing well and what we haven’t been doing well as far as greater global concerns about human experience, about civil rights, about equity, diversity, and inclusion in a different way. For me, I haven’t been in a rush to get back to work in a way that substitutes what was exciting work for me previously. I’m excited to be a part of a new kind of work, whatever that decides it’s going to be, through collaboration. There’s a way to be really stressed out about all of this, and certainly, I take it seriously, but I have this hopeful sense that maybe we’ll end up making something even more exciting. Some of these institutions that honor filmmaking, that honor music, that honor theater, they get criticized for being stuck in a rut. That we don’t open the span of the viewer, the span of celebration enough, and perhaps a format change, or something as rigorous as what’s happening in the world right now, will create something more interesting for all of us to make together.