“Boys State” Directors Amanda McBaine & Jesse Moss on Their Timely Doc

The documentary Boys State (now streaming on Apple TV+) follows four teenagers navigating a week-long annual program in which a thousand high school seniors in Texas create their own mock government. Winner of the Documentary Grand Jury Prize at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, the film is like a riveting mix of a soap opera, Lord of the Flies, and Breaking Away. The Credits spoke to directors Amanda McBaine and Jesse Moss about the making of Boys State, and its examination of young men coming of age in the time of ‘fake news’ and Trump.

More than just a political film, Boys State offers a window into how young men are growing into adulthood, and the challenges of being a boy at this time in the US. How did that aspect surprise you?

Amanda McBaine: We had these big questions in our heads about the health of democracy, and polarization, and so many things. When we got to Texas, we recognized what an incredible window we had to boyhood in 2018, around when #MeToo and toxic masculinity conversations were happening. Suddenly we saw we had this vantage point into how our young men are growing up in this atmosphere, and to what extent that plays into politics. We saw machismo and fronting, and tribal groupthink. Some of it is very Lord of the Flies. I had a lot of preconceived ideas of what I’d see, and a lot of them were met, but then there was an enormous amount of surprise in the range of masculinity that I saw, and the range of power that empathic leadership had, even in this space.

Jesse Moss: We see two models of leadership, of empathy versus a sort of militant strength. We understand that those are being worked out in national politics in different ways. It’s a kind of struggle of optimism and hope versus a dark cynicism. We hadn’t fully anticipated the degree to which we would have a really valuable prism, or perspective, into this contest of wills and masculine identity formation.

There are some very honest interviews and authentic interactions, some of which came out of the interview room you created.

Moss: As vérité filmmakers, we really prize capturing those dramatic, intimate moments as they happen. That was really the project of this film, but what we recognized was, this is also a really highly performative space, and there might be something happening on the surface that was different from what was simmering beneath. The interview room, which we built as a set, was a way to get our subjects offstage and let them have a moment of quiet contemplation and reflection. We began to learn through the week that what we were seeing wasn’t necessarily what they were feeling. They were struggling and sometimes sharing these very intimate feelings about the moral choices they were confronting as political actors in this space. A whole other level of the story emerged out of those interactions.

McBaine: It was a reflective space, as opposed to a reactive space, and it was essential to their transformation through the week.

What were some of the conscious choices for how the movie was filmed, especially considering you used six different cinematographers?

Moss: They are all artists in their own right, but we very much did have a style guide. One of the challenges of having a big team was making sure everybody was on the same creative page. There was a very intentional look to the film. One of the decisions was to shoot on a prime lens, a 35mm prime, which is unusual for a vérité documentary, where you typically want the flexibility of a zoom. We could move everywhere in the space, which was very exciting, and that meant that we could shoot on the prime lens, a very shallow depth of field, and really isolate our subjects in the frame from the background. That’s important in these sometimes ugly institutional spaces. Also, we shot widescreen, 2.39:1, which is unusual for documentaries, but we were really committed to making a big-screen movie.

How did you choose your cinematographers?

Moss: They are all part of Kamera Kollektiv in New York, and they all already had a dialogue with each other, and a shared commitment to the same practice. They were excited by the prospect of working together, which they don’t normally get to do.

All of you working in tandem must have been a powerful experience, given the intensity and chaos of the Boys State program.

McBaine: The collaborative piece could have gone very sideways at certain moments if we weren’t all in sync, like when three of our main characters, who are all being followed by different camera people, end up in the same room together. That means that there are three cameras in the same room, and to shoot that without getting the other cameras in the shot, and to shoot it well and cover it as a scene, really required the kind of beautiful ability to listen to and move with each other. That kind of choreography and level of experience is very rare. They were able to do that, and I can’t explain to you how special that is when you have the right people working with you.

In what way was Boys State special to you as filmmakers?

Moss: We are used to owning and controlling every aspect of production and having really small crews. This was a real surrender of ego and a leap of faith.

McBaine: Jesse and I have worked together for 20 years, and we’ve been married for almost as long. We have worked on many films, and generally, it’s Jesse in the field with a camera. It’s very intimate. We shoot it over 2 years, and then we all collect in the writing room over the next year. For this project, we needed everybody to be in the field, including me, and that required a certain kind of letting go of ego. That project, at this point in our career, was kind of wonderful, especially when you trust the people you’re working with on that level. To me, this was kind of a revelation in that way.

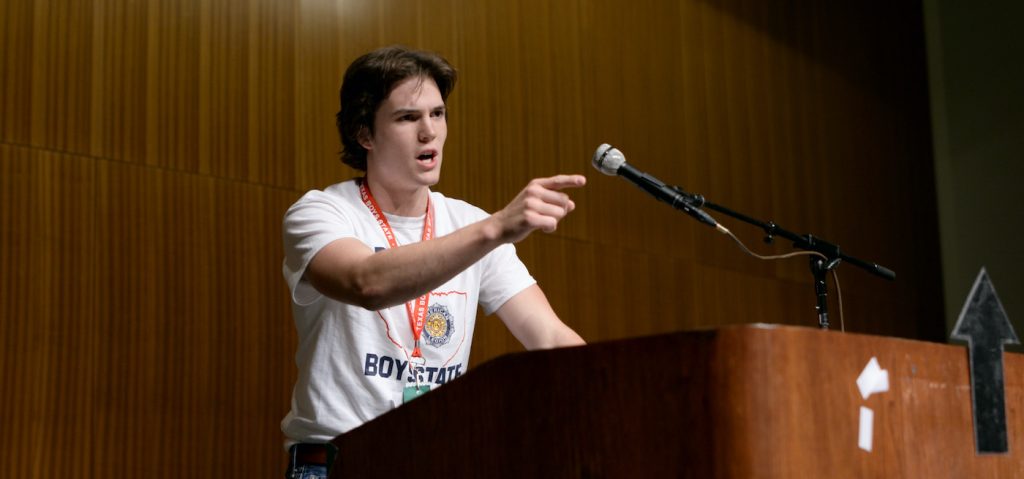

Featured image: René Otero in a still image from ‘Boys State.’ Courtesy Apple TV+