Director Matt Wolf on His Uncannily Timely Documentary Spaceship Earth

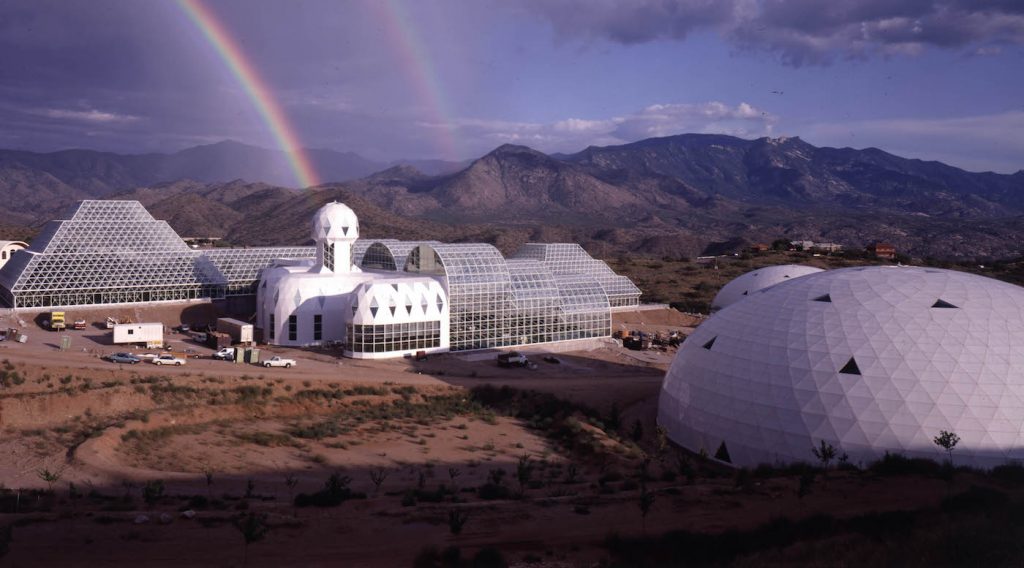

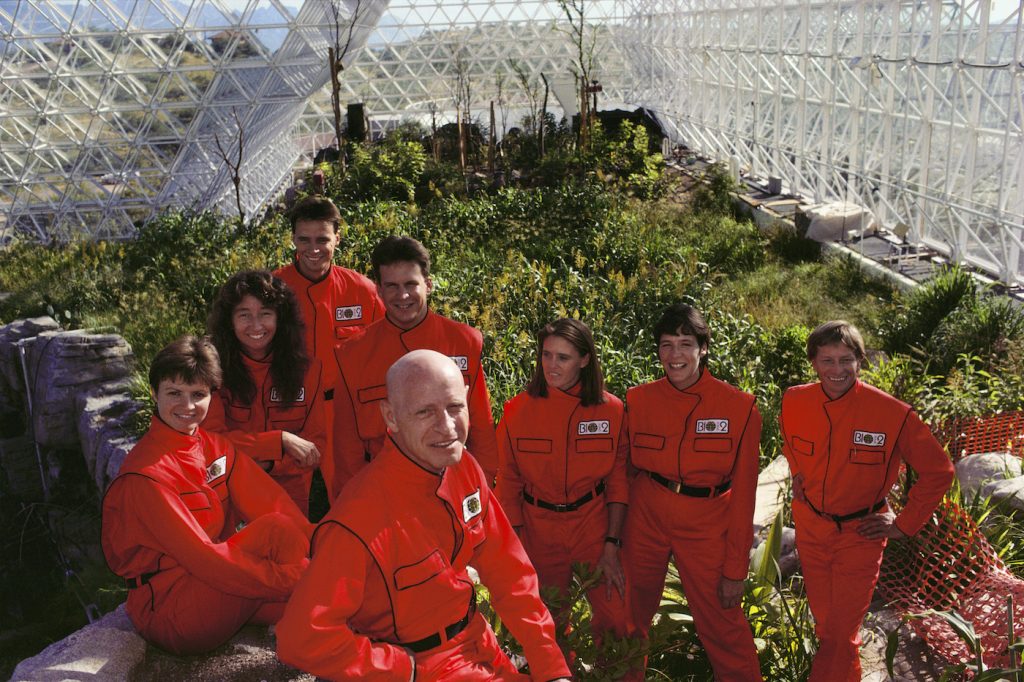

Spaceship Earth tells the fascinating, timely story of eight men and women who, in 1991, stepped into a sealed replica of Earth’s ecosystem to live a fully sustainable life for 24 months. Their world was called Biosphere 2, engineered by inventor/investor John Allen, and the experiment in which they participated, deemed a global media phenomenon. Spaceship Earth is available now on Apple TV, Amazon, Google Play, FandangoNow, Vudu, DIRECTV, DISH, and longtime NEON partner Hulu.

Spaceship Earth’s director Matt Wolf (Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project) was just a young boy when the “biospherians” began their historic research and had no memory of it. When a few years ago he came across images of the group and learned about their experience, he knew he wanted to make a documentary that told the entire tale. He and co-producer Stacey Reiss (The Perfection) combed through hundreds of hours of archival footage for the film, a 2020 Sundance premiere that is being distributed by NEON (Parasite, Portrait of a Lady on Fire) via a unique and expansive platform given the coronavirus shutdown.

“While making this film, I never could have imagined that a pandemic would require the entire world to be quarantined. Like all of us today, the biospherians lived confined inside…often under great interpersonal stress,” wrote Wolf in his director’s statement. “But when they re-entered the world, they were forever transformed. In light of COVID-19, we are all living like biospherians, and we too will re-enter a new world.”

The Credits spoke with Wolf about having NEON support the film, sharing producer responsibilities, and detailing a narrative that during its time was marred somewhat by controversy. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

It’s an interesting time to be releasing this movie.

You know, it’s a real boon to have a project like this to focus on right now. It’s up and down, but I’m happy to be focused on getting the film out there because I hope it starts a conversation to make some sense out of what’s happening.

You must be thrilled to have NEON behind Spaceship Earth, what with the distribution platform it’s offering. Everyone is going digital and streaming, but this plan is quite extensive and even goes beyond with drive-ins, safely accessible city pop-ups, etc.

Yeah, I was so excited when NEON came to us with this idea of releasing the film quickly to respond to the situation at hand and to recognize this kind of uncanny connection with the story. It’s not just dropping the film on streaming sites, it’s really thinking in an outside-the-box and more expanded way about what moviegoing means, what’s that collective experience, and how can we emulate that in times when people are isolated. Obviously drive-ins and pop-up projections are super cool, but what NEON is also doing is allowing small businesses, organizations, and institutions, anything from a little restaurant to the Smithsonian Museum, to host virtual screenings and events. So people who are constituents or customers or community members of these groups can choose to stream the film from their websites and that supports both the business as well as NEON, so it’s an interesting kind of partnership.

Fortunately, you had a treasure trove of archival footage and images to work with: 600 hours of footage alone. What was the process for going through all this material? Was it daunting at times? Was there anything you would have liked to included but didn’t?

Yeah, I make films that have a lot of archival footage, so 600 hours is a lot, but it’s not impossible in terms of the work that I do. I have the fortune of working with a great team who also shares our enthusiasm for archival footage. So we were able to wrangle that material and, of course, there’s lots of stuff that didn’t make the cut. What was so remarkable is that this is a story that has so many twists and turns, somewhat byzantine in its complexity, and there was footage that covered every beat of the story. That is so unusual and very extraordinary. It was really a process of collaboration to mine the material in a way that allowed us to discover the story and to shape it based on what exists.

How did you and your co-producer, Stacey Reiss, work together? Did you share or divide responsibilities?

Stacey is an incredible, creative producer. She is my partner hand-in-hand in the development of the film, from its earliest genesis to its completion. The second I found images of the biospherians that sparked this idea, I was texting her frantically saying we have to make a film out of this material, and from that point on we had a very copacetic partnership in which we divided and conquered. She is really gifted at forging and managing key relationships to allow a project of this scope and complexity with so many stakeholders involved. She facilitates collaboration in a really brilliant way.

Were any of the biospherians resistant at first and were you given any stipulations about what materials could or could not be used?

There was a lot of trust, I think, by stating our intentions and being clear that we wanted to tell a story with nuance that took a long view of the project, as opposed to something sensational or something that replicated the prevailing narratives out there about Biosphere 2. We gained a lot of trust that we would use this material in a responsible and thoughtful way, and we’re so grateful for that.

They seem like a group that would want their story told.

In some ways, yes, they were very eager to have their story told. But then they had been burned by the media, which had rebuked them and had torn down their life’s work, so it’s a mixed feeling of a desire to be recognized and also a reservation about having their work misconstrued.

You wrote in your director’s statement that part of your goal with this film was “to tell a story that we believe has been misunderstood.” Was this difficult given some of the controversies that arose about the project’s authenticity?

To me, the fundamental flaw of the project was a crisis of public relations. There was a lack of clarity in defining the ground rules for the experiment; there were many unknown aspects about what would happen. And unfortunately in the media, the management and the participants to some extent put up the expectations that they were gonna be sealed in there, nothing would go in and out, and that was the core goal of the experiment, and that wasn’t the core goal. So to me, it was important to represent their shortcomings in terms of communication and public relations, and also to report truthfully on what actually happened and what some of the obstacles they faced were, and how the media’s perception of the project ultimately impacted the outcome of it as well.

In addition to sustainability, science, transformation, and family, what other themes do you hope shine through?

I think that one of the really special elements of the film is that you can pursue incredible things, you can achieve incredible things, and they may not work as planned. They may not be defined as successful as you wished. But if relationships around those collaborations last, there’s something very profound about that and I think that is an inspiring aspect of the story that drew me in as well.

Featured image: The ‘Biospherians’ pose for the camera during the final construction phase of the Biosphere 2 project in 1990. Left to right are: Mark Nelson, Linda Leigh, Taber MacCallum, Abigail Alling, Mark Van Thillo, Sally Silverstone, Roy Walford, and Jayne Poynter. The 3.1-acre air- and the water-tight building became their home for two years. Biosphere 2 was designed to allow the study of human survival in a sealed ecosystem. The costs of this controversial, $150 million project were met from private funds. The Biosphere 2 project building is at Oracle, Arizona.