Legendary Animator & Oscar-Nominee Glen Keane on Teaming up With Kobe Bryant, his Disney Past & More—Part I

In light of the tragic news of the death of NBA legend Kobe Bryant, his daughter Gianna Bryant, 13 (the second oldest of Bryant’s four daughters with his wife, Vanessa), and seven other people in a helicopter crash in California, we are re-posting this interview with animator Glen Keane, who worked with Kobe on their film Dear Basketball, which ultimately earned them an Oscar for Best Animated Short Film.

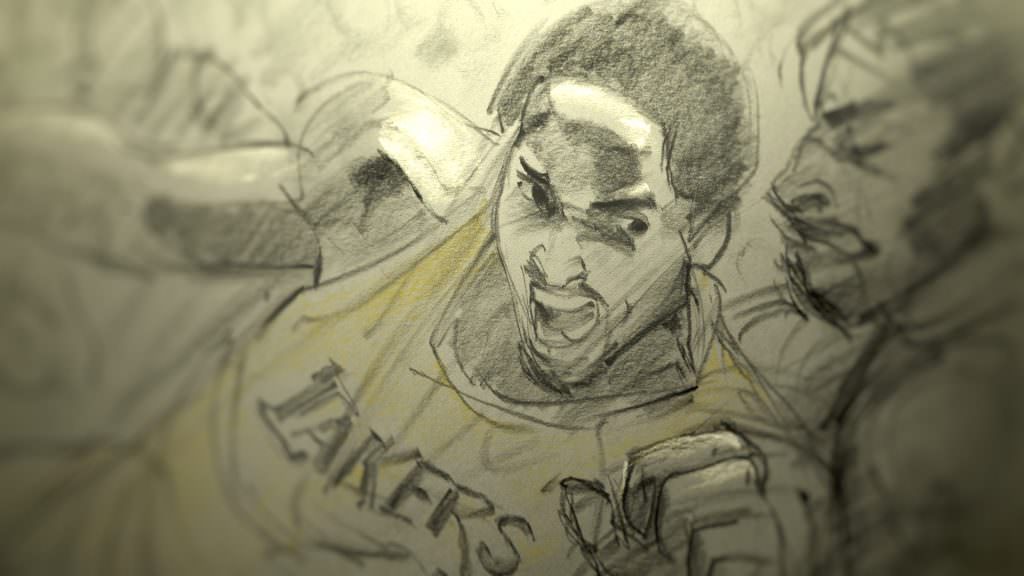

Glen Keane is not just a living legend. He’s a Disney Legend (yes, that is an official title). He worked for the studio that Mickey Mouse built starting in the ‘70s as a character animator on such features as The Rescuers and Pete’s Dragon and played a huge role during the second Golden Age of Disney animated features that spanned the ‘90s. But in 2012, like many a cartoon hero or heroine yearning for new adventures, Keane, now 63, decided to go it alone. As a result, he is now an Annie winner and an Oscar nominee for his short Dear Basketball, which pairs animated images of Lakers legend Kobe Bryant with the retired player’s self-penned heartfelt goodbye to the sport that gave him so much.

In this first of a two-part interview, Keane looks back at his Disney past and also on the new opportunities that have come his way since going solo.

Since leaving Disney, you have done a project with Motorola with a short, Duet, which treated animated movement in an entirely new way. You did a short for the Paris Ballet. You then teamed with Kobe and composer John Williams on Dear Basketball. Next is a full-length feature for Netflix, a female-driven fantasy in collaboration with China. You are not just challenging yourself but are on the cutting edge. It seems being untethered from a studio has worked out for you.

Picasso once said “I am always doing that which I cannot do in order that I may learn how to do it.” I feel like this has defined my artistic career since leaving Disney. There is a thrill in learning something new. Somehow that sense of discovery and childlike wonder seeps into what you are making and the audience can feel it. The first opportunity that came along for me post-Disney was to animate in a three-dimensional space for Google Spotlight Stories. For this, I animated a short film called Duet at a 60-frame-per-second rate and put the camera in the audience’s hands as we used a mobile phone gyroscope technology to track the animation in any direction the viewer may choose. It was crazy.

Then I was invited to work with a ballerina at the Paris Ballet and create an animated short.

Following that project, I worked in virtual reality drawing with Tiltbrush and did a short little film called Step Into the Page, which you can see online. Riot Games (the gaming company behind League of Legends) subsequently invited me to explore the development of their character “Lux” who is driven by an inner light — also viewable online. Kobe asked me to animate his poem Dear Basketball, and now I am beginning to direct a very unique animated feature with Netflix and China’s Pearl Studio called Over the Moon. Working by my side on all of these projects has been my producer Gennie Rim and my production designer is Max Keane, my 37-year old son.

What do these projects all have in common and why, after all you have accomplished, do want to keep in the game?

What all of these post-Disney endeavors have in common is that they have each enabled me to step into these unique worlds and allowed me to simply be me. I have been given incredible creative freedom, for which I am tremendously grateful, and all of them have challenged me to learn something entirely new.

I am guessing you learned something new about yourself when you worked on Tangled. It was supposed to be done with 2-D animation but then, when the Pixar duo of John Lasseter and Ed Catmull took over Disney animation as well, they wanted Disney proper to switch to computer-animated features. From what I understand, it was you who, in your role as supervising animator, helped the CG artists on the project to instill in their work the craftsmanship, humor and humanity that was the studio’s signature from its start. I am also guessing that without your leadership on Tangled, which was based on Rapunzel and turned out to be a surprise box-office success in 2010, there wouldn’t have been a Frozen franchise.

Tangled was a project I worked on from 1996 (while doing Tarzan and Treasure Planet) until it was released in 2010. That’s a long time. I learned about enduring and not giving up when everything inside you wants to quit. I also found that the principles of hand-drawn animation needed to be applied to CG animation in deeper ways than they were at that time. Ollie Johnston, my mentor, once told me, “Glen, one day you’re going to do greater things than us.” I wished for many years he had never said that. I mean who is going to make an animated feature that is better than Pinocchio? I felt doomed to fail. Until one day after I had been working at Google, I realized he was not speaking about “greater” in quality but greater in application. He was speaking about how this new generation and the ones to come will be applying traditional animation principles into fields as vastly different as ballet, basketball and virtual reality.

You are still dedicated to doing hand-drawn animation yourself. Why does maintaining the human touch count so much with you?

When I was 9 years old, my dad, who created a comic called The Family Circus, gave me a book on drawing called Dynamic Anatomy by Burne Hogarth. He said to me “Glen, I’m a cartoonist, but you’re an artist.” This was my goal to pursue a career in fine art. However, when my portfolio was inadvertently sent to the wrong department at Cal Arts, I found myself in the middle of the world of animation. This “error” turned out to be providential for me as I discovered animation to be the ultimate art form. I believe if Rodin, Degas or Michelangelo were alive today they would embrace animation as an art form that would allow them to spread their creative wings in ways we have barely touched. For tens of thousands of years, drawing has been integral to creative expression. I don’t see that stopping now in the very thin slice of time we live in. I see drawing as a seismograph of the soul. As my son once told me, “Every line we make is a unique creative expression never to be repeated.” This experience and moment was what Kobe was looking for in creating Dear Basketball. The hand-crafted quality has deep personal value to me as an artist.

Animation has grown and evolved in so many ways since you began at Disney. Where do you see animated entertainment heading in the future?

I was taught that the key to Disney animation is sincerity. I discovered that means one must live in the skin of the characters you animate. They must become real to you. I have been a mermaid and a Beast, but I never imagined I could be Kobe Bryant. This is the magic of animation and whatever form it may take technologically, sincerity will continue as the key.