How Russian Doll’s Cinematographer Owned the Night in Netflix’s hit Series

“Joel was amazing for coming up with solutions for turning New York into a Russian Doll city.” The Big Apple already boasts its share of Russian dolls, mobsters, peroshkis, and more, of course, but cinematographer Chris Teague is instead referring his gaffer, Joel Minnich, and the recent hit Netflix series of the same title, which he shot.

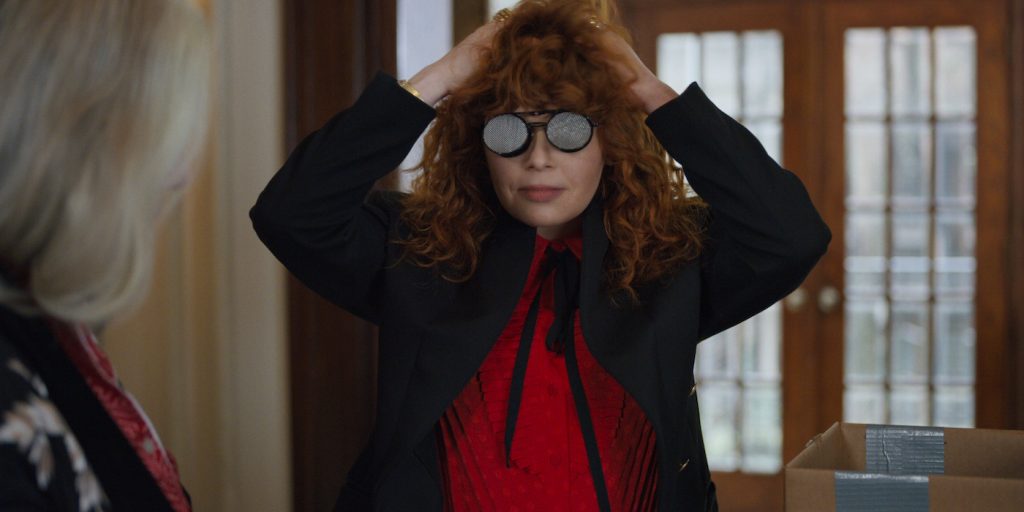

Starring co-creator, co-producer (and for one episode, director) Natasha Lyonne, Russian Doll follows the various embedded and unraveling realities of Nadia, an ennui-ridden game coder who finds herself— somewhat game-like—repeatedly dying on her 36th birthday. She “resets” in front of the same bathroom mirror afterward, left to try and unlock the riddle of why she keeps coming back, in the words of Steely Dan, to “do it again.”

And since the series is so completely suffused, and at ease with, its New York-ness, its Jewishness, and its femaleness (though Nadia eventually discovers Alan, another “repeat dier,” played by the also excellent Charlie Barnett), the City that Never Sleeps was already providing plenty of embedded layers to unpack—just like those dolls.

Teague, however, was referring to the nature and availability of light in this primarily night-set series. He was shooting “on a Red Helium, with Leica Summilux Prime lenses. I wanted to shoot with something that was very fast, with a very wide aperture.”

So fast, with that Helium sensor, that he was shooting with nearly 8k resolution, part of a production pipeline where Netflix commands all its shows to be ultimately finished in HDR—High Dynamic Range—with a sharpness and resolution that people will really start to notice once the expected upgrades to 4k monitors starts to spread.

“HDR is such a new thing for everybody,” Teague allows, and “kind of a challenge, because it’s impossible to monitor on set in any accurate way,” mostly because color-accurate monitors, he says, are still so expensive.

But what he meant about his gaffer, Minnich, with whom he’s “worked together on a bunch of different projects, and has a shorthand,” is sometimes the gear worked too well.

“I do find the HDR to show itself more prominently when you’re shooting into bright windows, street lights, etc. When there are so many of those highlights in the frame, and you pull them down, it can start to look artificial. When you’re shooting into windows, just embrace it’s going to be bright,” Teague says. “The interesting thing with night now, the cameras are so sensitive, that we have too much light to work with.”

Which is where Minnich came in: “Joel had eight of this Astera tubes—four foot long LED tubes They have a built-in battery, are wirelessly controlled—and you can hang them, or tuck them around a corner.” All of which went toward a visual approach to keep Nadia “separate from her background,” as she increasingly realizes she’s (almost) alone in revisiting the various timelines available to her.

And while Teague credits a sharpness to the Leica lenses, he also notes there was a problem with the surfeit of light now available for night shoots. “They were making the scene too bright, or the color wasn’t appropriate for the scene.” That’s when Minnich would “bring in our own sources,” after also either “trying to block off street lights,” or if the city was amenable, turn them off altogether.

The look, in other words, steadily reveals that while Nadia is clearly of New York, for the course of this journey, she’s not always in it, in a day-to-day (or night-to-night) sense.

Teague worked with production designer Michael Bricker to help create that particular NY. “He’s this incredibly talented, terrific collaborator,” Teague says. “The conversations we had were very in depth and a lot of fun. He had a lot of ideas that on another show, I would not have embraced,” including walls that Teague might have originally thought were too dark, or too reflective, especially tiled walls, like the bathroom where Nadia keeps “rebooting.”

“But on this show,” he says, “it felt good to push those things.”

He and Becker also helped define the three main “spaces” where the story unfolded. Nadia’s party (in her friend Maxine’s apartment) is saturated with more color, Alan’s “cooler, more monochromatic” apartment, and finally “Ruth’s place, the closest Nadia had to home. It’s more neutral, but not necessarily bright and cheery.”

Ruth would be her aunt, played with clear brio by Elizabeth Ashley. Ruth is also a therapist (who reminds people who utter the word “crazy” that “we don’t use that word in this house,”), and the sister of Nadia’s haunted, estranged — and departed — mother.

“We wanted to feel it had weight,” Teague continues. “It was about not using soft sources. The quality of light was flattering and pleasant, but it wasn’t like there were streaks of cheery sunlight. It was still kind of low-level.”

One aspect dampening the cheer is Nadia’s realization, about halfway through, that each time she “dies,” even though she gets to return, she might be leaving grieving family and friends behind on each of the previous timelines. It’s an unsettling notion, and with the news that Netflix has greenlit a second season, we’ll see if it warrants further exploration.

And if Teague is back to shoot it—though he’s off lensing the current season of GLOW right now—he will doubtlessly be able to plunge into whatever timeline the second season brings, without too much looking back over his shoulder: “I try to do as much work as I can on set with our DiT (digital imaging technician) so when we do get into color, it’s more a fine-tuning process than anything else. Because (in TV) there just isn’t time for that.”

Not that there hasn’t been time to savor things, just a little: “As a cinematographer, it’s not every day you get an opportunity to do a project like this,” he says. Even if turns out that “day” is the same one unfolding, again and again.