How the Entertainment Industry is Advancing Artificial Intelligence

The 69th Berlinale’s tag line this year is “the personal is political.” Within that scheme, where does artificial intelligence fall? Last Friday, the MPAA and the entertainment law firm Morrison & Foerster tried to answer that question, hosting a panel on technological innovation in the film industry, with a particular focus on AI. The eight panelists came from a variety of backgrounds: a lead representative from the US independent film industry, the communications head of a German digital society research institute, a BMW spokesperson, a book manuscript forecaster, and others. Tacit among their diverse presentations was that, despite being so heavily represented in front of the camera as an evil to be vanquished, behind the scenes, AI is here to stay. And minus a few caveats, that’s not a bad thing.

Moderated by Christiane Stützle, the co-chair of Morrison & Foerster’s global film practice, and Christian Sommer, Germany’s country representative to the MPA, the panel touched on the wide-ranging industries in which AI is a growing factor, from self-driving cars to VR entertainment. Within film, however, where is AI already in use such that a typical viewer—one more interested in finding entertainment than whether robots helped create it—might be interacting with the technology? For now, it’s Netflix.

Giving the keynote, Dr. Klaus Goldhammer, a media economics professor and the founder of Goldmedia, cited the streaming service’s start page, tailored individually to subscribers not just in terms of what they see, but how it’s all presented, right down to smart algorithms that determine the films’ artwork. Also closer to the business side of things, Netflix’s use of AI was mentioned as a possible future of film financing. Alexandra Lebret, the managing director of the European Producers Club, pointed out the commonalities between a group of humans trying to determine how and whether to finance a project and AI doing the same. Either party would be making predictions, but for a company like Netflix, “it’s maybe all algorithm,” she said. “They can give a value to a script and package and finance a film this way.”

Lebret pointed out that (for the time being) “AI isn’t good at creativity. AI is good for prediction.” And prediction, for any industry, is good for balance sheets. Both Lebret and Goldhammer cited J.P. Morgan, which already has AI models in use to determine whether to finance proposed films. With this particular AI advancement, however, comes the need for responsibility, particularly among the industry’s major players. Jean M. Prewitt, the president and chief executive officer of the Independent Film & Television Association, noted that this technology essentially replicates what people are already doing. “If someone comes in and says I want to make an edgy, low-budget romantic comedy with Julianne Moore, even I can figure out what the marketplace estimates are,” she said. “You pull the last 15 movies, say how did that work in Germany, and come up with a ballpark figure.” Making it possible to replace that process with the push of a button “is huge.” But it shouldn’t be the lone determining factor, particularly if all the data is held close to the chest by a few industry players. “If that becomes the only data point that’s relevant to whether a film gets made, that’s the antithesis to creativity,” Prewitt noted. “Creativity means risk. And if you can’t embrace that, you probably can’t make anything that’s really mind-changing the world.”

Aspects of AI more closely tied to the creative process itself were also discussed. Sven Bliedung, the director of Volucap, continental Europe’s first commercial volumetric capture studio, preferred to change his own audience’s mind with a three-dimensionally rendered special guest, introducing into the discussion’s screened simulcast—an elderly gentleman seemingly plunked into the middle of the panelists. Bliedung, whose work has focused on VR production, hopes to bring this sort of rendering together with AI in the near future, allowing you to add a digital version of Hollywood talent to whatever’s being filmed. (Did this bring up ample legal rumbling among the other panelists? Yes, but not nearly as much as it elicited the wonder that perhaps digital George Clooney could soon be conjured up in people’s kitchens.)

Other AI prognoses spanned the futuristic and the practical. When Volucap’s AI compatible 3D human renderings are fully achieved, one advantage Bliedung sees is that an actor’s physical age will no longer be crucial to any particular role. The advantage here isn’t the destruction of the Botox industry, but the ability to free up a shooting schedule for something like the Harry Potter franchise, with directors no longer racing to keep pace with the aging of their young stars. Of course, this particular use of AI faces technical and legal hurdles before any practical application.

On the other side of the industry, however, AI will likely replace humans in determining age ratings for films in Germany within the next couple years. “Everybody’s thinking about new possibilities that technologies are opening up, and in many fields, we realize that algorithms are pretty good decision makers,” said Christiane von Wahlert, the managing director of the Head Organization of the German Film Industry (SPIO) and its Voluntary Self-Regulatory Body (FSK). The FSK is developing a web-based dynamic prototype, based on the current criteria for film age classification, that would allow an algorithm to replace the adults who make these determinations for children now.

It’s leaps like these that make work harder for panelist Derek Wax, an executive producer on the British version of the series Humans. The show explores the familial and societal issues wrought by fictional synths, AI entities living among present-day people. Since beginning work on the series in 2014, the technological world has been “catching up with what we’re doing,” he said. Yet it would seem he’s at the helm of an industry that has created its own problem.

The executive manager of 3IT Innovation Center for Immersive Imaging Technology, the company that developed the tech behind Bliedung’s 3D construction of human bodies (or for the layperson, George Clooney in your kitchen, maybe, one day) was also on the panel. Though this technology was originally created for the communications sector, Kathleen Schröter pointed out, over the past two years, the entertainment industry has been the field responsible for pushing it forward. But neither creatives looking to hang onto their careers nor those concerned about robot overlords (speaking of concepts pushed by the film industry) should worry at present. “At the end of the day there’s no art in artificial and no intelligence in the intelligence,” Schröter said. “It’s just math.”

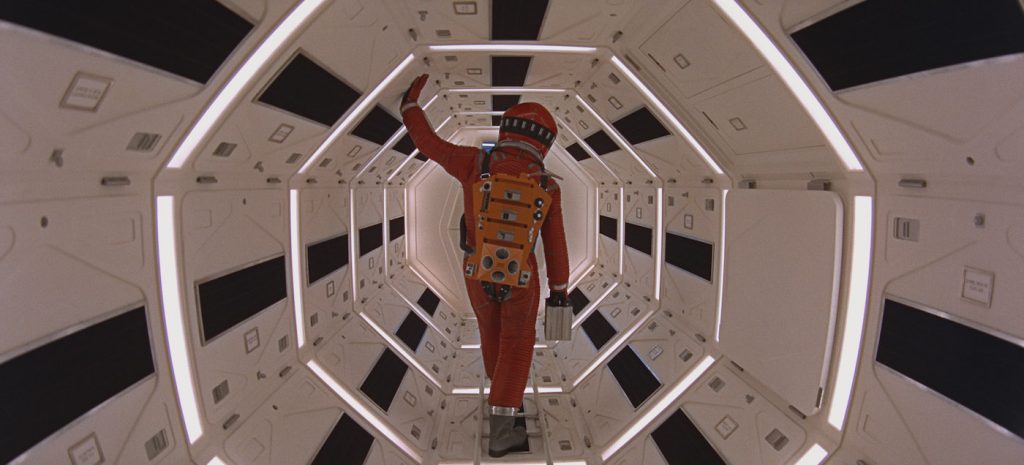

Featured image: ‘Humans’ key art from season 3. Courtesy AMC