Oscar Watch: Suspiria’s Prosthetic Makeup Artist on Turning Tilda Swinton into an Old Man

The original horror film Suspiria, made by Dario Argento in 1977, was wild and colorful, and the palette of Luca Guadagnino’s version of the story conveys quickly that this is not a remake. The dance company at the center of the story, next to the Berlin Wall, is bleakly lunatic, as are the street scenes of 1970s Berlin outside, where RAF protests hold sway and it is always raining.

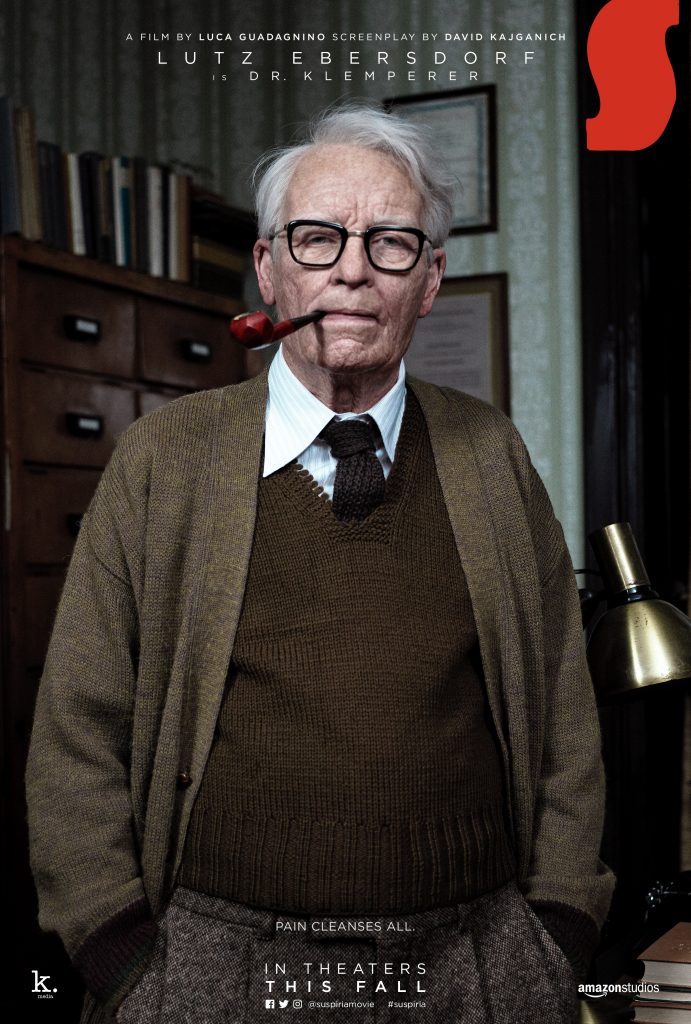

The film opens on ex-dancer Patricia (Chloë Grace Moretz) paying a desperate visit to her therapist, an elderly gentleman operating out of a genteel, run-down home office. She is hearing voices, which we hear, too, and she claims a mother of some kind has occupied her body, but she soon gives up on Dr. Klemperer, who expresses concern but not sincere belief. In the U.S., a Mennonite woman is dying, and back in Berlin, her youngest daughter, Susie Bannion (Dakota Johnson) arrives at the Markos Dance Company for her audition. She is granted Patricia’s former spot in the company and the dorms upstairs, and begins her tutelage under the severely elegant head teacher, Madame Blanc (Tilda Swinton), and given the modest economic enterprise of any modern dance company, what seems like too many on-site matrons.

The matrons are a coven, quietly involved in an internal power struggle between Madame Blanc and Helena Markos, an unseen entity who believes herself the true Mother Suspiriorum, one of three ancient entities. All she needs, of course, is the sacrifice of a young, healthy dancer. One of these already didn’t work out, and there is internal division as to why, but it’s generally agreed among the coven that Susie is just the fit for human sacrifice. As they wait for Susie to be “ready,” however, one dancer, Olga, tries to leave the company, and another, Sara, begins snooping around the building’s hidden chambers; they both meet gruesome physical fates, though nothing quite so horrifying as what Mother Markos turns out to be afflicted with, when we finally meet her.

Even though everything going on at the dance company, besides the actual dancing, is fairly horrible, Suspiria inspires specific 1970s nostalgia: the colors are muted, the gore is artistic, everyone speaks quietly, nobody talks too fast. The film’s hair and makeup are as restrained as the clothes, living quarters, and plain gray streets. The head of the hair department, Manolo Garcia, eschewed “stereotypical” 70s style feathering as too American, instead favoring plain, long dramatic locks in a nod to several looks of the era. “We thought that the world of the dance company had to be truly organic to our research, which expanded from the world of Pina Bausch to the avant-garde in general,” he said. “This long hair brought an uncanny feeling of womanhood that could be consistent with the tone of the movie, its thematics, and some of the back stories, such as the final black sabbath scene, where you experience the wild violence of a coven of witches and their fetishism for hair.”

Throughout this exploration of womanhood, only one man appears often, Dr. Josef Klemperer. After speaking with another young dancer, he begins to believe Patricia, showing up around the school in between crossing back and forth between West and East, in search of a wife long lost to the Holocaust. Klemperer, it has come out, was played by an unknown actor named “Lutz Ebersdorf,” unknown because he is Tilda Swinton. For the second time, prosthetic makeup artist Mark Coulier drastically aged Swinton—he was responsible for her aging grand dame character in Grand Budapest Hotel—and in this instance, with the assistance of key prosthetic make up artist/sculptor Josh Weston and key prosthetics makeup artist Stephen Murphy, he also made her male (the entire hair and make up team for the film included 25 people). Suspiria’s gore is simultaneously sophisticated and retro, but turn Tilda into a man, keep it secret for months, and that grabs all the headlines. Luckily, we got to speak with Coulier about his process there, as well as working off Guadagnino’s inspirations and creating some of the more shocking characters of Suspiria.

In designing the film’s character aesthetics, much were you influenced by the original Suspiria?

It all came from Luca, really, and our research. Luca had a lot of paintings by an Austrian artist called Alfred Kubin and so most of his symbolism and reference came from Kubin’s work, and also an artist called Beksiński, a Polish painter. So we took our references from all over, really, but he’s got specific filmic references, as well. He loves the sort of body horror of David Cronenberg and these very intense sequences. So we sort of picked out a few of Luca’s influences, and then we were just trying to tap into what he likes to create. So it was a lot of discussions. We were thinking about the film for a long time because we didn’t get the green light until quite late on. We had about a year to collect images, references, and swap information. That was important. Luca’s very specific about what he wants, and he’s very creative and he’s very encompassing—he likes to get your involvement, as well. Between [all of] us, we hopefully managed to put what he imagined onto the screen.

You also made Tilda Swinton into an elderly person in the Grand Budapest Hotel. Does the technical process differ entirely? How did it work?

There were several things we had to do. First, it’s actually quite hard to disguise somebody completely under makeup. When you’re watching the film, we hope that you don’t realize it’s Tilda, or you just buy into the character of Klemperer. Then we had to make sure she was masculine enough, so we had to thicken her neck up, a lot, because Tilda is very thin-necked. Then we had to alter her jawline quite heavily. And then we had to get rid of those high cheekbones, so we flattened all of her face out. We changed the shape of her cranium, her ears, everything really. But the main things that made her look masculine were the neck and the jawline.

Was it always intended to keep this secret?

There was a lot of secrecy on set. We had to call Tilda by her actor’s name, Lutz, because we were transforming her into Lutz Ebersdorf. She kept it quiet and stayed in character when she was on set, so she wasn’t ever Tilda when she was wearing the makeup, she was always Lutz. And the idea was that hopefully nobody found out, and everybody accepted this character in perpetuity. But obviously word gets out, it’s too difficult to keep something like that quiet nowadays. I’m not surprised word got out, which is fine, really—if it generates interest, then it’s great.

We also heard Swinton requested a set of male genitalia.

That’s right, yeah. Tilda, in an actorly fashion, wanted to feel masculine, as much as possible, really. So we did do a little set, and they were just like little weighted sacks pinned onto the inside of the costume. A bit like Al Pacino wearing silk underpants when he played Al Capone. It’s something that actors like to feel the part, you know.

By the way, I know there’s tons of attention on Tilda Swinton as an 82-year-old man, but were you responsible for that thing poor Olga turned into? How did that come about?

It was a combination of us and the visual effects department. We created a facial prosthetic and fake dentures, for when she gets a broken jaw. And then we did a fake arm prosthetic, and she’s wearing a fake leg prosthetic, so the arm and the leg are bent weirdly, completely out of shape. And then the visual effects team removed her real arm and real leg, so she ended up twisted and contorted into a shape a human can’t get in. The idea, from Luca, was that she was pulverized, beaten to a pulp, by these vicious women, people who are trying to protect their identity. He wanted it to be visually quite shocking, and maybe, when you watch the movie, it is quite a shocking sequence.

Was there an intentional contrast between Death and the putrefying witch, both who are introduced in that final scene?

The character that comes around at the end is basically some evil entity, summoned by the witches or the powers that be, to come and get rid of all the Marko-ites. Anyone following Helena Markos is killed by this death character. The death character was always just a representation of death—that’s what we called the character, Death. So, yes, it was always designed to be feminine and elegant, but horrific and terrifying at the same time. Originally it was going to be digitally enhanced to be quite tall but ended up as it was because Luca thought that the image was powerful enough, the character was powerful enough to come in at the end and wreak havoc.

Featured image: Lutz Ebersdorf (in reality Tilda Swinton) as Klemperer stars in Suspiria. Courtesy Amazon Studios.